A Beginner's Guide To Vermouth

People are most likely to come across vermouth on the menu of their favorite cocktail bar. This flavored, aromatic wine is a key ingredient in many classic cocktails including the Americano, martini, and Manhattan. Despite its pervasiveness, members of the American public often have a difficult time pinpointing what vermouth is. Fewer still have enjoyed the wine on its own. This, however, is set to change.

In past decades, the production of vermouth was predominantly based in Europe. Recently, the rise in craft alcohol culture has increased the interest surrounding vermouth. Now, several artisanal iterations of the wine are made in the U.S. These bottles, as well as other options made in Europe, consistently demonstrate that vermouth is just as well-suited to drinking straight as it is mixing into a cocktail.

As the wine's versatility becomes more well-known, the public's willingness to try it increases. This has sparked a recent vermouth renaissance in several countries, namely Spain. At the moment, drinking neat vermouth is not an established practice in the U.S. There are, however, many reasons why it should be.

Vermouth is a fortified wine

As a beverage category, fortified wine is routinely misunderstood. This was highlighted to Eater by bar manager Lee Carrell: "I think the average consumer actually doesn't understand what fortified wine is, or that fortified wine actually is a category. They're not aware that sherry and vermouth and port are fortified wines, they don't really understand what it means to have distilled spirit added to a wine base."

For clarity, vermouth is defined as a fortified wine. This means it is wine, which is strengthened — otherwise known as fortified — through the addition of a spirit, usually brandy. Vermouths routinely range between 16 to 22% ABV. In Europe, vermouths consist of at least 75% wine. Either red or white wine can be used as the drink's base.

Inside the umbrella of fortified wines, vermouth belongs to the sub-group of aromatized wines. These are fortified wines that have been flavored with herbs, spices, and natural flavorings such as wormwood, orange peel, and cinnamon bark. These additions give vermouth its wide-ranging flavors.

It's important to note that, in order for it to be classed as vermouth in Europe, at least one herb from the Artemisia wormwood family must be used to flavor the liquid. Outside of this obligation, vermouth producers are given free rein in what ingredients to include. Naturally, this results in a huge range of flavor profiles being available.

It has been drunk for centuries

As with many popular alcoholic beverages, vermouth has been drunk for centuries. Originally, herb-laced wine was seen as a medicine in much the same way bitters — like amaro — were. Bar manager Lee Carrell highlighted vermouth's medicinal origins when speaking to Eater: "Vermouth has been around for a very, very long time and was used in Greek times by Hippocrates, who was known to have several different types of vermouth that he would prescribe for different ailments. Even the Sumerians, pretty much all of the ancient people who were making wine were in some way adulterating their wine and aromatizing it."

Modern iterations of vermouth can be traced to the Kingdom of Savoy, which spanned lands in modern-day France, Italy, and Switzerland. Here, a variety of vermouths were both produced and enjoyed. It is thought the two early styles, sweet and dry, were created and defined in this kingdom.

The popularity of vermouth was confirmed in Turin during the 18th century when a man called Antonio Benedetto Carpano produced the first commercially available vermouth. His name is still associated with vermouth today, thanks to the highly thought-of Carpano brand.

It was consumed as an aperitif

Although it is often used in cocktails, vermouth was traditionally enjoyed as an aperitif: a drink consumed before eating to stimulate the appetite. This association is as old as the drink itself. Hippocrates originally prescribed his vermouth as an appetite stimulant.

Bar owner K.P. Sykes highlighted how the association between aperitif and vermouth endures in an interview with Food & Wine: "To gain a better understanding of vermouth you must first understand the liqueur and spirit category of Aperitifs. The etymology of apertif comes from the Latin verb aperire, which means to open. In this case, opening the appetite before a meal. So in short, vermouth is an aromatized and fortified aperitif wine."

As cocktail culture took hold in recent decades, the practice of enjoying vermouth as an aperitif dwindled. Yet, some countries, including Spain, have turned this trend around. While there are several factors at play, one is the increased number of vermouths on the market. This has sparked renewed interest in the beverage.

In the U.S., Europe's aperitif culture is slowly gaining traction. It remains to be seen whether the rise of aperitif culture will elevate the popularity of drinks traditionally associated with it. If it does, vermouth will surely benefit.

There are three main styles of vermouth

Broadly speaking, there are three main styles of vermouth: sweet — otherwise known as red or rosso — dry, and bianco. As the name suggests, sweet vermouth contains the most sugar of the three styles, at least 130 grams per liter, if it is made in the European Union. While red in appearance, sweet vermouth is often made with white grapes. This style of vermouth is traditionally mixed with dark spirits to make cocktails like the Manhattan.

In comparison, dry vermouth is much lower in sugar. The EU specifies that dry vermouth can have a maximum sugar content of 50 grams per liter, although many have less. Botanicals that are regularly used to flavor dry vermouth include juniper and coriander. These vermouths tend to be aromatic and herbaceous. Extra dry vermouths demonstrate similar flavors but contain even less sugar. Both dry and extra dry vermouths are often used to make martinis.

In between these two styles, you have bianco vermouth. This is a semi-sweet vermouth that can present a variety of flavors depending on the producer's whims; from floral to bitter, sweet to spicy, these vermouths are incredibly wide-ranging. When combined with their medium sugar content, this makes bianco an attractive option for bartenders; they allow them to add an unexpected spin to cocktails by simply swapping out sweet or dry vermouth for bianco.

Vermouths can also be categorized by country

Traditionally, the two main styles of vermouth — sweet and dry — were referred to by the names Italian and French. This is because the prominent sweet, red vermouths were produced in Italy around Turin. French producers, on the other hand, became known for the dry, pale variety. That being said, such binary divisions are not as useful today, given the broad range of vermouths made in countries all over the world.

Mixologist Michele Marzella highlighted that some generalizations can still be made about vermouth-producing countries when speaking to Gothamist: "Italian vermouths with spices inside are more typical, and similar in all Italian vermouth is clove and nutmeg. The American vermouths are different because the way to [produce] the vermouth is more open. They're also different because American vermouths are more dry and oxidized, the acidity of the wine is more present. American vermouths are more similar to French vermouths."

Spanish vermouth, known in the country as vermut, is often cited as being the most suitable for drinking neat. This is because the style traditionally forgoes the bitterness inherent in Italian vermouths, and focuses instead on more palatable citrus flavors.

It is integral to many famous cocktails

Many of the world's favorite cocktails feature vermouth. Dry vermouth is present in the martini. Sweet vermouth is present in both the Manhattan and the Negroni.

It is generally accepted that vermouth is added to all these cocktails for two reasons. The first is that they dilute the high-proof spirits, making them more palatable. Secondly, vermouths are packed with flavor, thanks to the high number of herbs and spices used to flavor them. This means that a single measure of vermouth adds a staggering number of flavor notes to a cocktail, increasing its complexity manyfold.

As a supporting act, vermouth is hard to beat. This ensures that it's still as relevant in contemporary mixology as it is historically. This is evidenced by bar owner Nate Adler, who still reaches for vermouth when designing new cocktails, as he explained in an interview with Gothamist: "Vermouth makes incredibly unique cocktails. A lot of times I'll sit down for a tasting and I'll say, 'This doesn't have anything Spanish in it, let's just add vermouth.' And it usually goes really well. It's a good supplement, for sure."

A few different companies dominate vermouth production

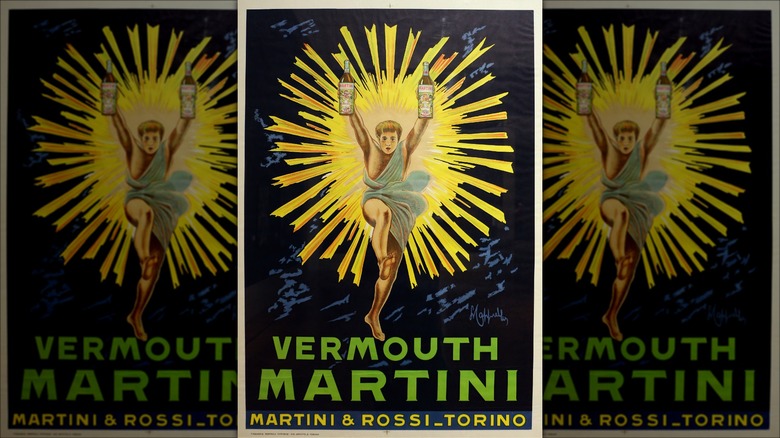

Vermouth's renaissance has seen artisanal producers popping up in countries across the world. In terms of volume, however, vermouth production is still dominated by a few well-known brands. Largest of all is Martini & Rossi which began to produce vermouth in 1863. Now owned by Bacardí, Martini remains incredibly popular; the company sold 9.7 million cases in 2021 alone.

Most prevalent does not mean best, however. In a poll conducted by Drinks International, the majority of 100 award-winning international bars named Cocchi their preferred vermouth brand. Martini only ranked third. A large driver of Cocchi's popularity is its Vermouth di Torino, which was relaunched in 2011. Since this time, Cocchi Vermouth di Torino has become immensely popular, thanks to its impeccable flavor.

No market is consuming more vermouth than Spain at the moment — and it is still growing at a rate of around 9% each year. Spanish brands like Vermuts Miró are perfectly placed to make the most of this demand. The vermouths produced by this brand are known to be easy to drink and are especially suited to serving neat.

Vermouth di Torino is particularly desirable

Vermouth di Torino is a vermouth that has been awarded protected geographic origin by the EU. This legislation prevents vermouths from being labeled as Vermouth di Torino unless they abide by a range of technical standards that were defined in 2017. These include that the vermouth be between 16 and 22% ABV and that at least 50% of the base wine and all herbs — apart from wormwood — come from Piedmont.

These rules do not mean that all Vermouth di Torinos taste the same, as was highlighted by vermouth expert Francois Monti to Wine Enthusiast: "There's nothing in regulations of Vermouth di Torino I remember that defines the taste profile. They define some aspects of production—but not the flavor profile."

One of the most prestigious Vermouth di Torinos is Cocchi's Rosso. This has been called the gold standard of vermouth and consistently impresses with a flavor profile that starts fruity before the flavors of cocoa and spices take over. A perfect execution of Italian vermouth's iconic bittersweetness is the liquid's lasting impression.

Carpano Antica Formula is another Vermouth di Torino that is very highly thought of. This expression of the fortified wine includes both saffron and vanilla in its recipe. The end result is a complex vermouth that is beloved the world over.

There are many American producers of vermouth

Unlike vermouth made in the EU, American vermouth has to adhere to much fewer guidelines and restrictions. For example, wormwood doesn't have to be included in American versions of the product for it to be labeled vermouth. While some purists may groan in dismay at the lack of this restriction, the flexibility allowed to producers has seen several innovative vermouths being made in the U.S.

One well-respected American brand is Matthiasson, located in California's Napa Valley. As a winemaker, Matthiasson has access to an exceptional base product made from a rare grape called flora. Another Californian winemaker that has turned to vermouth is Andrew Quady, founder of Quady Winery. Quady likes to use orange muscat as the predominant grape variety for his vermouth's base wine. This wine is transformed into three different vermouths each flavored with a variety of herbs including lavender, gentian, and orris.

La hora del vermut is a respected Spanish practice

Nowhere has experienced a vermouth renaissance quite like Spain. The country has, in the past decade, transformed vermouth from a relic of the past into one of the most popular beverages in the country. In 2021, Spain consumed over 3 million nine-liter cases of vermouth.

A large quantity of vermouth is consumed during what the Spanish call la hora del vermut, or the vermouth hour. This is a cultural practice wherein people take a break from the day by enjoying a glass of neat, iced vermouth. A lot of bodegas cater to la hora del vermut by making their own house vermouth and serving it on tap.

While la hora del vermut is a fantastic opportunity to enjoy a delicious drink, it is mainly seen as a way to unwind and socialize. August Sebastiani, president of 3 Badge Beverage Corporation, noted this in an interview with Wine Business: "La Hora del Vermut is a time to relax with good company. It's a time to pause for a refreshing, light and easy-to-drink cocktail before your evening festivities."

Opened vermouth should be stored in the fridge

Those new to vermouth often make a common mistake: storing it on the shelf as opposed to in the fridge. As it is a wine, storing opened vermouth at room temperature will make it spoil rapidly, dulling its flavor and even turning it vinegary.

Cocktail consultant Jamie Boudreau explained how poor storage practices can negatively influence people's opinion of the fortified wine when speaking to SFGate: "People have an aversion to vermouth, and quite frankly, it's well founded. Even if you keep your vermouth in the fridge, after a week you'll notice it has a different flavor. If you keep that vermouth on a shelf, it's going to taste terrible. That's why people don't like vermouth."

While refrigeration does slow down spoilage, it does not prevent it, or other spoilage processes, from occurring. As a result, even refrigerated vermouth will spoil over time. Once opened, a bottle is best drunk in under a month. Three months is generally seen as the maximum length an opened vermouth should be kept.

Vermouth is often used in cooking

While vermouth is an essential part of bars, both home and professional, the wine should not be limited to beverages alone. In fact, some chefs would argue that vermouth is just as integral to the kitchen as it is to the bar. For example, you can use vermouth in most situations that call for white wine. In this instance we would advise the use of dry vermouths; when replacing red wine a cook is better served turning to bianco or sweet vermouths.

The culinary uses of vermouth are many and varied. Dry vermouth can be used to make a sauce to top fish, for example. They are also very well-suited to deglazing pans. Sweet vermouths make a great addition to stews.

The main advantage of using vermouth in place of wine is flavor. As mentioned previously, the multitude of herbs and spices used to make vermouth means even a single measure packs an incredible variety of flavor notes. As such, vermouth adds much more complexity to a dish than regular wine.

One thing to be wary of is vermouth's trademark bitterness. This can easily overwhelm a dish. As such, cooks are best off seeking out milder versions of the fortified wine, such as those produced in Spain.

As it becomes more popular, other styles are appearing

Today, vermouths can no longer be shoehorned into the three categories of sweet, bianco, and dry. As demand for fortified wine has grown, new styles have been created or repopularized by producers. One new style is rosé vermouth which is defined by its pink color and semi-sweet to sweet taste. Flavors of berries and red fruits are often present.

Other producers are opting to change the base of vermouth from wine to sherry. Sherry-based vermouths have a long history originating in the 1800s. However, the style has only been revitalized in recent decades thanks to vermouth's growing popularity.

A fantastic example of how these two styles can combine is Lustau's sherry-based Vermut Rosé. Beverage director Amy Racine described this vermouth to InsideHook as follows: "It comes from the same area (and producer) of great sherry, and you get a slight hint of that saltiness of sherry in the wine. It also has a juicy blackberry and strawberry aroma, yet is just off-dry. My favorite is to pour this over one large rock and drop in a dried red chili pepper for a little kick."

Vermouth is just part of the growing fortified wine trend

Vermouth is the flagbearer for the category of fortified wines, a category which also includes the likes of port and sherry. Surprising as it may seem, this category has become popular with millennials due to a combination of nostalgia and other factors.

What's more, the prevalence of fortified wines in cocktail bars has seen younger people introduced to this category in an appealing way. This was highlighted by bar owner Mike Capoferri to VinePair: "I'd say in the past five years or so there has been an exponential increase in the use of fortified wines as cocktail modifiers, making those ingredients much more visible to the consumer. Also, thanks to bars like Dante, aperitivo culture has become more mainstream in the U.S., leading to people drinking more vermouth and other wine-based aperitifs."

As a result of its popularity with younger generations, the fortified wine market is experiencing significant growth. One forecast predicts that the fortified wine market will reach a value of $27.3 billion by 2028. To put that into perspective, that's approximately $5 billion larger than the value of the global non-alcoholic beer market in 2022.