The Most Influential Chefs Throughout American History

The culinary history of the United States has been crafted through tradition, exchange, and immigration. It all began with indigenous cuisine, the food grown and cooked by America's many indigenous nations. These cultures domesticated some of today's most popular crops, including squash and corn.

Generations of indigenous cuisine were altered forever with the arrival of the Spanish colonists. The ensuing Columbian Exchange saw an array of new foods introduced to North America. At the same time, staples like potatoes found themselves settling into the diets of those across the world. Thus, foods such as beef — that are now thought of as quintessentially American — became established on the continent.

From then through to the modern day, chefs have worked with these ingredients. In doing so, they've helped transform American food into a cuisine influenced by many different cultures. While everyone who cooks American food has been a part of this process, there have been a few chefs with a larger impact. Here is a closer look at fifteen of those cooks.

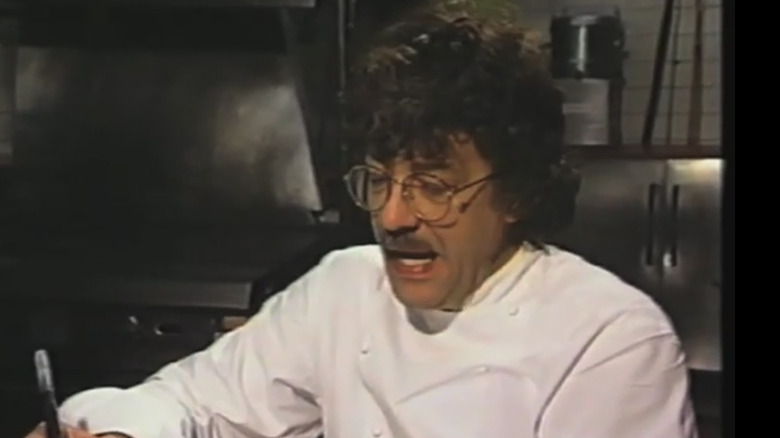

Jean-Louis Palladin

Farm-to-table cooking is now so popular that it is practically a culinary punch line. Yet, there was a time when obsessing over ingredients was unheard of, at least in America. Jean-Louis Palladin, a French chef who earned two Michelin stars by the age of 28, was one of a few chefs who changed that.

After earning his stars in France, Palladin moved to the U.S. in 1979. He then opened his Washington D.C. restaurant, Jean-Louis, at The Watergate Hotel. There, Palladin sought out the very best American ingredients to use in his kitchen. Palladain's mentee, legendary chef Éric Ripert, explained as much to The New York Times: "He would take an afternoon to drive 150 miles to get a ham, and I think that influenced a lot of people. Because of Jean-Louis, people went scuba diving for scallops because he would accept nothing less. If today we have all these amazing products and organic food is so fashionable, he was the father of that."

As a founding father of America's farm-to-table movement, Palladin's culinary legacy has directly contributed to some of America's most beloved restaurants, including places like Blue Hill Farm. His approach to cooking also marks him as a chef that was truly ahead of his time.

Edna Lewis

Edna Lewis was an American-born chef and food writer. During her lifetime, she had a huge impact on American cuisine. She did this, in part, by serving amazing Southern food at her friend's restaurant, Café Nicholson, in New York City. Lewis cooked at Café Nicholson starting around 1950, turning out dishes like fried oysters, Virginia ham, and chocolate soufflés. Such distinct cooking brought a host of famous guests to the restaurant, including the likes of Salvador Dalí and William Faulkner.

Cooking provided the basis for Lewis' culinary career, yet her greatest impact didn't come through working with pots and pans, but pen and paper. After suffering from a fall in the late 1960s, Lewis began writing recipes. Her first cookbook "The Edna Lewis Cookbook" was released in 1972. Her second book, "The Taste of Country Cooking," highlighted how brilliant food was being made by Black communities in the country's south.

"The Taste of Country Cooking" not only prompted an acceptance of both Black and Southern cooking but also seasonal eating. Chef Alice Waters illustrated this to The New York Times: "She showed the deep roots of gastronomy in the U.S. and that they were really in the South, where we grew for flavor and cooked with sophistication. I had never really considered Southern food before, but I learned from her that it's completely connected to nature, totally in time and place."

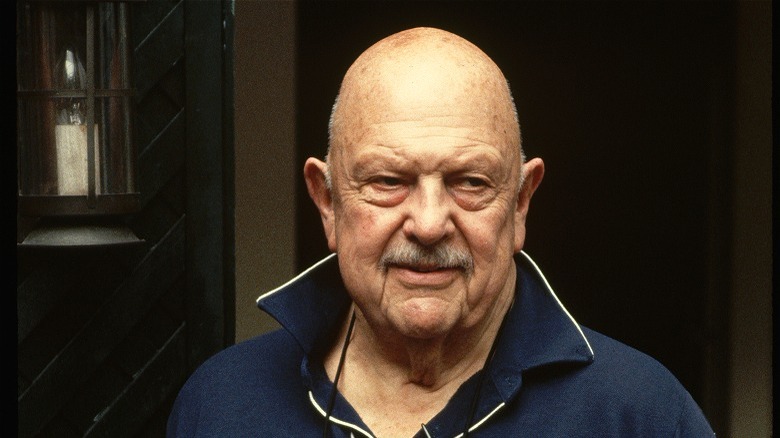

James Beard

Now a legendary name, James Beard started his adult life trying to make it as an actor. Beard got his start in the culinary world by launching a catering business, Hors d'Oeuvre, Inc., which provided food for cocktail parties. He followed this up in 1940 with a book on the matter.

To many, Beard's legacy is one of defining American cooking. This perception came about in the post-war years, thanks to the chef having his own segment on America's first cooking TV program. After being beamed into homes around America, In 1954, The New York Times named Beard the "Dean of American Cookery." He later cemented this claim by publishing "American Cookery," an influential book that authenticated the nation's cuisine in a way not achieved before.

Of course, many people know the name James Beard because of the annual food awards that are held in his name. These prestigious awards, known as the Oscars of the food world, are designed to celebrate those professionals in the U.S. that champion good, equitable, and sustainable food. These criteria reflect Beard's own appreciation of American cuisine in all its forms.

Alice Waters

If Jean-Louis Palladin is the father of America's farm-to-table movement, Alice Waters is the movement's mother — and her famed restaurant Chez Panisse its home. Waters opened Chez Panisse in 1971 after a trip to France opened her eyes to how other cultures were connected to the land and food in a way that fast food-fuelled America was not. Her restaurant set off a revolution, first in California and then nationwide. Now it is commonplace for restaurants to only cook local, seasonal food and to name farms and producers on menus. Waters and Chez Panisse started these practices.

Whereas chefs like Palladin solely relied on their food to do the talking, Waters, as an activist, has turned to charities and education. She founded The Edible Schoolyard Project in 1995, a nonprofit that uses organic school gardens and food spaces to teach children the values of nourishment, stewardship, and community. In an interview with Forbes, Waters explained why teaching children to grow and cook their own food was important: "It's the best way we can address climate because we're educating the next generation. It's more important than it has ever been."

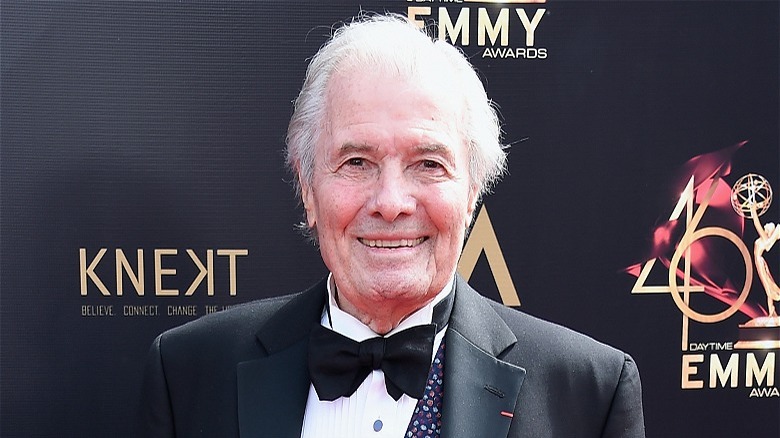

Jacques Pépin

Jacques Pépin is another French chef that has had a significant impact on America's cuisine. Pépin began his culinary career at his parent's restaurant, before continuing his career in Paris. His French cooking career culminated in a job as a personal chef to French statesman Charles de Gaulle.

Pépin moved to the U.S. in 1959 to work at the New York City restaurant Le Pavillon, one of the finest restaurants in the country. Yet, Pépin exerted an even greater influence when he left Le Pavillon for Howard Johnson's, where he and the namesake owner revolutionized what has become the quintessential American dining experience: restaurant chains.

After a car accident, Pépin left professional cooking behind and focused on becoming a culinary educator. Books such as the 1976 "La Technique" taught a generation of chefs how to handle and prepare ingredients with painstaking accuracy and attention to detail. This has undoubtedly contributed to the quality of food cooked in the U.S. today.

At the time of writing, Pépin is 87 years old. He remains as dedicated to technique as ever. He highlighted this fact to The New York Times: "You have no choice as a professional chef: you have to repeat, repeat, repeat, repeat until it becomes part of yourself. I certainly don't cook the same way I did 40 years ago, but the technique remains. And that's what the student needs to learn: the technique."

Cecilia Chiang

To say America's cuisine has been influenced by other countries' cooking would be an understatement. For far too long, however, foreign cuisines have been oversimplified, disregarded, and even demeaned in America. Often it falls to individuals to right these wrongs and re-educate the American populace about foreign cuisine. Cecilia Chiang was one individual who did so.

Chiang was born in China. After running a successful restaurant in Tokyo, Chiang moved to San Francisco in 1960. Her restaurant, the Mandarin, opened shortly after. Early on, Chiang decided to turn her back on the popular Chinese-American dishes of the time, like chop suey. Instead, the Mandarin served authentic Northern Chinese dishes. Highlights of the menu included tea-smoked duck and moo shu pork.

Chiang's impact on Chinese food in America was immense. Not only did she introduce Americans to traditional Chinese cooking, but she also created the blueprint for Chinese restaurants to provide excellent service as well as food. She continued to hold restaurants to high standards long after she had retired, as she highlighted in an interview with SFGate.

Emily Meggett

Emily Meggett was the author of the first prominent Gullah Geechee cookbook "Gullah Geechee Home Cooking." This book was a landmark bestseller that finally brought Gullah Geechee cuisine — a subset of American Southern cooking — the national attention it long deserved. Kayla Stewart, the book's co-author, highlighted Meggett's impact in an interview with The New York Times: "She left us with a lifetime of work that was overlooked and undervalued for years. She really moved the needle in terms of how we're talking about Gullah Geechee cuisine and culture."

There could not have been a better advocate for Gullah Geechee cuisine than Meggett who was born and raised, like many generations before her, in the Gullah Geechee corridor (areas located throughout North Carolina and Florida). The generational knowledge was apparent in Meggett's cooking which was generous. It was also packed with flavor, as well as seafood, and vegetables.

Julia Child

Although Julia Child did not work in a professional restaurant, she had the training and experience of a chef. The former she gained by studying at the famed Parisian culinary institution Le Cordon Bleu. The latter was earnt by running a cookery school known as L'École de Trois Gourmandes alongside Simone Beck and Louisette Bertholle.

Of course, Child's greatest moment came with the publishing of "Mastering the Art of French Cooking" an over 700-page cookbook first published in 1961. This book, co-authored by Beck and Bertholle, was the first that made French cuisine accessible for American home cooks. What's more, the recipes and the ethos they represented were in contrast to the American cooking of the time which prioritized artificial and processed ingredients.

Child also used television to spread her message of wholesome French cooking. Starting on PBS, Child's cooking shows became a mainstay of American television, loved for both their informative nature and Child's entertaining personality. Geoffrey Drummond, a TV director who worked with Child explained the impact of her shows to Epicurious: "Julia really had a kind of double legacy. She brought respectability to real cooking in the kitchen to the American home for a whole generation. And so for many of those people, it was almost as if Julia had given them permission to pursue something in the food world ... She really was a mentor to many generations, from home cooks in this country to our top chefs."

Anthony Bourdain

By his own admission, Anthony Bourdain was not an exceptional chef. Instead, he was one of the countless hardworking food professionals that toil away in obscurity for decades. After working at the restaurant Les Halles, Bourdain grew famous for his writings and television appearances.

The first many heard of Bourdain was a New Yorker article titled "Don't Eat Before Reading This" which revealed the realities of professional kitchens in all their intense, grimy glory. This article proved the blueprint for Bourdain's first non-fiction book "Kitchen Confidential," where he examined his own cooking career, as well as the industry in his aggressive, cutting prose.

The huge success of "Kitchen Confidential" led Bourdain to television. There, he hosted two programs, "No Reservations" and "Parts Unknown". Both of these shows used food as a means of exploring different people, countries, and cultures in a novel and meaningful way. The effect this approach had on others was immense and long-lasting, as writer Kris Yenbamroong highlighted in Men's Journal: "Tony was the greatest advocate for saying 'yes.' He wanted people to see the world through other cultures' lenses and to open their hearts and minds to things they never thought were possible ... He pushed forward in the face of the unknown. He continues to inspire me to live a little bolder each and every day."

David Chang

David Chang's Momofuku empire has become so embedded in America's food scene that it is almost hard to remember a time without it. Chang's career took off with the opening of Momofuku Noodle Bar, a small restaurant that specializes in serving Japanese noodles. This approach, and the success that has sprung from it, is Chang's greatest impact on America's food scene.

A similar sentiment was highlighted by chef Joaquin Baca to The Washington Post: "People like us used to think that the only way to run a restaurant was the big model, the old school, the fine dining, and what Momo did was to break that mold ... Early on, we had so much industry crowd, we had chef de cuisines and sous-chefs from some of the most notable restaurants in the city, who would come in, and they were looking at us, like, pulling it off, and they were like, 'F— it, I can do this, too'."

Chang has also established himself in the media. He co-founded the short-lived but highly impactful magazine, Lucky Peach, and has been featured in a variety of television programs, including the Netflix hit "Ugly Delicious." Similarly to Bourdain, Chang uses food in these creative outlets to have bigger discussions on food culture and society.

Leah Chase

Leah Chase was born in Madisonville, Louisiana but spent the majority of her life in New Orleans. She came to cooking naturally, working in the city's French Quarter during World War II. Yet, it was in the Tremé neighborhood that Chase built her legacy, working in her in-law's restaurant which she slowly transformed into the Creole institution Dooky Chase's.

Dooky Chase's was a unique establishment in New Orleans, because, in its early days, it was the only place Black people could experience fine dining during the Jim Crow era. Chase highlighted this in an interview published by Serious Eats: "You have to understand what restaurants were in the black community then. Blacks didn't eat out much, because they didn't have places where they could eat. When I came in, I said I wanted to change this and that, whatever I learned from the other side of town. We started putting tablecloths on the tables and got it going."

The restaurant soon became a cultural hub for Black Americans involved with the Civil Rights Movement, like Martin Luther King Jr. Chase also served artists and writers, including James Baldwin. Chase's career not only established not only that Creole cooking belonged in fine dining restaurants, but also that Black people did too.

Thomas Keller

Thomas Keller is a titan in America's gastronomic world. This is partly attributed to his incredible success. The American chef leads two restaurants — The French Laundry and Per Se – that have both been awarded three Michelin stars. Coupling excellent French technique with incredible ingredients is the hallmark of Keller's cooking, but it's not the basis of his greatest influence. Rather, this comes in the form of mentoring.

Keller is an enthusiastic and dedicated mentor responsible for improving the careers of numerous chefs and food industry professionals. He explained his view on mentorship to FSR Magazine: "Mentorship is something that can be brief, and mentorship can be lasting. Mentorship can turn around—your mentee can become your mentor in the future. But one of the things we always talk about is our ability to remove our egos from the equations and appreciate the effort we're making toward one another ... what happens is quite extraordinary. That person becomes better than you. If that doesn't happen you haven't done a good job."

The list of Keller's mentees demonstrates the enormous influence his teachings have had on American — and global — cuisine. They include Corey Lee, the first Korean chef to earn three Michelin stars, molecular gastronomy chef Grant Achatz, and co-owner of Noma René Redzepi.

Mashama Bailey

Mashama Bailey is one of the best-known chefs in America. She has been featured in Netflix's hit TV series "Chef's Table", won the James Beard award for Outstanding Chef, and is the executive chef of The Grey, a restaurant that was named Restaurant of the Year by Eater. Most importantly, Bailey is a chef that is paying homage to and transforming Black cooking in a way that no one else is.

The influence Bailey wields is enormous. She is an inspiration to chefs everywhere, including Black chefs. Her influence and career thus far were explained by co-owner of The Grey, John O. Morisano, to The Financial Times: "If she continues to develop her voice and her point of view, could she be [like] Dr. Harris? Yeah. Does she want to follow in the footsteps of Dr. Harris and Edna Lewis and all those people who laid the tracks? She definitely does. And I think she should."

Nobu Matsuhisa

No chef has done more for sushi in America than Nobu Matsuhisa, the Japanese chef that first caused a storm with his Los Angeles restaurant Matsuhisa. Matsuhisa opened his namesake restaurant in 1987 and won instant fame for his unique style of sushi that incorporated elements of Peruvian cuisine.

While the dishes served at Matsuhisa, and the many Nobu restaurants that followed, changed sushi forever thanks to their flavor, Matsuhisa himself changed the process of sushi making by developing his own ten-finger, six-step technique. Matsuhisa highlighted this technique to The Peak: "My technique for making sushi involves using all ten of my fingers. It is a very delicate yet simple process, but it is also very difficult to master. The trick is you need to firmly but gently shape the sushi with the sushi rice to the point you can still see light passing through the sushi." With around 50 Nobu restaurants spread around the world, Matsuhisa's cooking technique has not only changed sushi in the U.S. but around the globe.

James Hemings

James Hemings was a man who did more to shape American cuisine than any other person on this list. Unfortunately, he is also likely the least well-known. This is because Hemings was an enslaved cook of Thomas Jefferson, the third U.S. president. As was so often the case with enslaved Americans, Heming's achievements were historically attributed to his owner, leading many people to incorrectly believe that it was Jefferson (and not his chef) who was responsible for laying the foundations of modern American cooking.

Hemings learned his craft in France during the 1780s, apprenticing under the day's leading chefs. Upon his return to the U.S. in the 1790s, Hemings cooked for Jefferson when he was secretary of state. During this time, Hemings cooked many French-inspired dishes that have become American staples today, including macaroni and cheese, ice cream, and French fries. After negotiating his freedom in 1796, he passed away five years later.

Despite being 36 when he died, Hemings' impact on American cuisine is unrivaled. Chef Ashbell McElveen agrees and highlighted the importance of Hemings' culinary legacy to Today: "His macaroni and cheese recipe that went from an enslaved kitchen in Monticello all around the world and became a global food, just like French fries ... We should all give thanks for this incredible individual who helped create fine dining in America."