The Contentious History Of Chop Suey

Chop suey is a dish many Americans will be familiar with; the mixture of stir-fried vegetables, meat, and either noodles or rice has long been a fixture of Chinese American restaurants. Today, it is an ingrained part of the United States' culinary lexicon.

Despite its ubiquity, the history of chop suey is unclear. Multiple myths, suggestions, and explanations point to the development of the dish, but none in a completely conclusive manner. As such, chop suey has been the cause of considerable debate, both academically and socially.

Some scholars view the dish as the perfect example of how American culture has treated Chinese – and other foreign — food over the years. Cycles of celebration followed by racist belittlement have muddied the origins of many immigrant foods in the United States, perhaps none more than chop suey. We have collected the various origin stories of chop suey in an attempt to clear the waters.

For a long time, the story began with Gold Mountain

Many people view chop suey as a uniquely Chinese American dish. For these individuals, the dish's logical beginnings coincide with the first wave of immigrants that came from China to the United States. The first Chinese immigrants were nearly all single men from the Guangdong province who were drawn to North America's west coast in the 19th century by tales of Gold Mountain, known as gam saan. The idea of Gold Mountain did not just pertain to the California Gold Rush but rather the idea that North America was a land where someone could make their riches.

San Francisco was a popular place for these immigrants to disembark. Some 25,000 Chinese people moved to California between 1849 and 1851. While some did go searching for gold, many decided to make a living by catering to the ever-growing Californian populace. Starting a restaurant was one way of doing so.

These restaurants typically served cheap, wholesome food, a category chop suey fits neatly into. One story names a San Franciscan restaurant, Macao and Woosung, as the birthplace of chop suey. According to this legend, drunk miners demanded food late one night and the tired owner served them scraps from around the kitchen stir-fried and served with rice. Although there is little evidence to support this legend, it demonstrates the importance Chinese restaurants had in California's nascent restaurant industry.

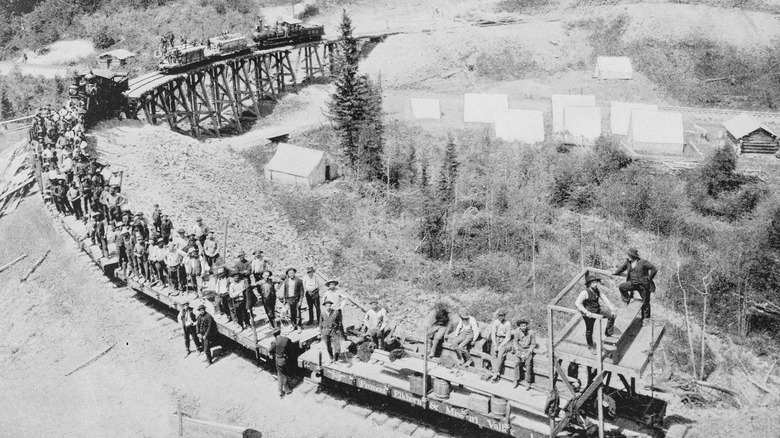

Chop suey was spread by the new railroads

While the Gold Rush has been suggested as one of many potential catalysts for chop suey's invention, there is little debate about how the dish spread: on the back of the country's new railroads. These transcontinental projects were built by a great number of Chinese laborers who were seeking work as the Gold Rush abated.

Businesses that catered to this workforce, including restaurants, naturally followed the rail works and many Chinese-owned businesses opened in the new railway towns. Once built, the railways also enabled the spread of Chinese restaurants across North America. Entrepreneurial individuals traveled further afield to open the first Chinese restaurant in a given area and avoid competition. This led to popular dishes, like chop suey, being enjoyed by large swathes of Americans outside of the west coast for the first time. The proliferation of Chinese restaurants would eventually give rise to the unique Chinese American cuisine we know today.

A popular myth is that chop suey was created by Li Hongzhang in 1896

While the previously mentioned theories surrounding chop suey's origins seem plausible, there are many other stories that are less believable. One is that Li Hongzhang, a prominent Chinese diplomat, got his chefs to invent the dish in 1896 after not enjoying the food that was served at a banquet held in his honor. Another variation of this tale is that Hongzhang popularized the relatively unknown dish by eating vast amounts of it at the said banquet. But both tales have little evidence to back them up.

Yet another story about Hongzhang inciting the creation of chop suey is based in New York City. In this telling, Hongzhang's cooks created the dish as part of a dinner, believing that the mixture of vegetables, meat, sauce, and rice would appeal to both American and Chinese palates. Again, this story probably has little basis in reality.

One man claimed to have invented it himself

While the stories around Li Hongzhang seemed to have sprung up out of thin air, a man named Lem Sen actively pushed himself into the chop suey conversation. He did this by accusing all New York restaurants that served chop suey in 1904 of copyright infringement. Sen, a born San Franciscan of Chinese descent, claimed he invented chop suey while working at Bohemian, a restaurant in San Francisco. The recipe was then stolen before spreading across the country like wildfire, or so Sen stated.

Sen's bid for compensation from all restaurants serving chop suey ultimately failed. His plot, however, had a huge, inadvertent impact: Chop suey was subsequently deemed an American dish with no connection to Chinese cuisine at all. In other words, chop suey was not authentic. The dismissal of chop suey as a purely American invention is one of the root causes of the dish's historical obscurity. It's a wrong many scholars have attempted to right.

Anthropologist E. N. Anderson insisted chop suey can be traced back to China

One of the most successful people to refute chop suey's American origins was E.N. Anderson, an anthropologist who worked at the University of California. Anderson argued that chop suey was actually a dish that originated in Toisan, a county in the Southeastern Chinese province of Guangdong. As the vast majority of early Chinese immigrants came to the United States from Guangdong, Anderson's suggestion seems feasible.

Other prominent writers, such as Andrew Coe, have written extensively on the topic and agree with Anderson. Coe explained the dish's Chinese origins to The New Yorker: "I believe that the chop suey served in New York's Chinatown back in the 1880s was a real Chinese dish, a local specialty from the Guangdong province town of Taishan, which sent the majority of Chinese immigrants to the United States. In the early descriptions, it's a mixed stir fry made from chicken giblets, bean sprouts, bamboo shoots, onions, tripe, dried seafood, and whatever else is at hand." The versatile and frugal nature of the dish is expressed through its name, tsa sui in Mandarin, or tsap seui in Cantonese. Both of these translate into something like odds and ends.

Historical records suggest chop suey was being eaten in the late 16th century in China

Although many believe that chop suey was invented in America during the 19th century, several historical documents indicate that a dish with the same name was being consumed in China as early as the 16th century. The most famous of these documents is "Journey to the West," a convoluted Chinese novel in which one of the main characters directly states that they bought a wok to make chop suey. The character plans to make chop suey with offal. This was the traditional means by which Chinese chop suey was made. Indeed, two chop sueys were served at a famous 18th-century banquet, one of which included both sheep liver and intestine.

Each province seems to have had its own version of chop suey. Most included offal along with various other ingredients such as bamboo shoots. The exact ingredients likely changed depending on what was available. This is true of Chinese American chop suey as well; ingredients can be added or omitted without drastically changing the dish. Yet, the general omission of offal and the Westernized flavor profile mark Chinese American chop suey as distinctly different from the collection of Chinese dishes it originated from.

Chop suey became extremely fashionable in America during late 19th and early 20th century

In the United States, chop suey reached the pinnacle of its fame during the early decades of the 20th century. At this time, major newspapers, like The Washington Post, were publishing articles on the dish as well as recipes. The exposure resulted from the dish's growing popularity in America's upper class who served it at parties and functions as a means of exoticizing their party. Chop suey subsequently became a status symbol and was even served at the luxurious Victoria Hotel in Chicago.

The chop suey fad did not introduce Americans to traditional Chinese flavor profiles. Instead, the dishes they ate were almost tailor-made for the American palate. Andrew Coe highlighted this phenomenon in The New Yorker: "[A]s more and more non-Chinese began to eat the dish, restaurant owners realized that they could sell a lot more by adapting the dish to American tastes. All the weird, imported ingredients disappeared, replaced with easily-identifiable meats and the essential accompaniments of bean sprouts, onions, and celery. Over the decades, this Americanized dish became a kind of overcooked and essentially flavorless stew that somehow hit all the buttons for our taste buds. From 1900 to 1960 or so, chop suey was one of the most popular dishes in the country, up there with ham and eggs, hot dogs, and apple pie."

Growing racial tensions saw Chinese food demonized

Although Chinese American food and restaurants gained popularity in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Chinese Americans did not. Throughout this time period, Chinese immigrants were met with racist injustices that frequently involved violence, the suppression of their rights, and considered destruction of their customs. A great deal of the anger Americans directed at immigrants was rooted in a fear that the Chinese would take work away from American men, leaving them unable to support their families.

One of the many ways Americans attacked Chinese immigrants and their culture was to belittle their food, a practice that is still used against immigrant communities today. Rumors that the Chinese immigrants feasted on rats and mice were rife throughout the 19th century and did not abate even when Americans developed an appetite for chop suey. This oxymoronic stance is still common and was explained to NBC News by celebrity chef Eddie Huang: "I think that the change in people's perceptions and their 'open-mindedness' towards Chinese food is only happening when it's packaged and presented to Americans in a way they like."

This dissociation between the Chinese food Americans enjoyed and the plight of the people who made it was starkly evident during the 20th century. During this time, chop suey was one of the most popular dishes in the nation. At the same time, the Chinese Exclusion Act prevented any further immigration and also ensured all Chinese immigrants could not become U.S. citizens.

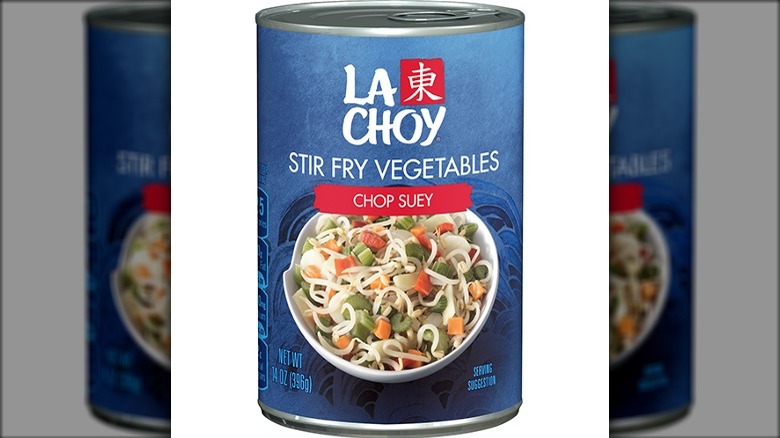

Canned chop suey highlighted the dish's decline in America

While the exclusion of offal is one of the key ways American chop suey differentiated itself from China's chop sueys, it wasn't the only. Another, distinctly American influence on the dish was the rise of canned chop suey vegetables.

La Choy, a company founded by two friends from the University of Michigan, was the most famous supplier of such a product, and its oriental-inspired marketing and products have become synonymous with Chinese American cuisine. Yong Chen, a professor of history at the University of California explained this to Taste: "Non–Chinese American individuals and organizations such as La Choy played a role in the development of Chinese food in America. This is something that some of us who write about that history sometimes did not pay sufficient attention to."

Despite the ardent use of fresh ingredients in La Choy's early years, the cheap canned chop suey vegetable product did nothing to help the dish's image. Before too long, the dish had fallen from popularity and was seen more as a tropist joke than a respectable dish.

Chop suey all but disappeared after The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed

As we've seen, the rise of canned chop suey mixes and the loss of the dish's Chinese heritage both contributed to a fall in prominence. Yet, it was the end of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943 and the subsequent renaissance of Chinese cuisine in the United States that really pushed chop suey out of the culinary picture. Anthropologist Bennet Bronson told The Chicago Tribune why: "First of all, you are finally getting chefs who are trained in real Chinese food. Also in the '70s and '80s, with Americans becoming more exposed to Chinese culture through books and travel, you get a greater demand for authentic food. And then, with more new Chinese immigrants arriving, you see the revival of Chinese restaurants for Chinese people."

Although not professionally trained, the life and career of iconic Chinese American restauranter Cecilia Chang epitomize the transformation in Chinese American cuisine during this time. Chang's iconic restaurant Mandarin is seen by many as the birthplace of modern Chinese cooking in America and was known for serving Sichuan specialties like a tea-smoked duck. Chang made a conscious decision not to serve chop suey at her restaurant, citing a desire to serve real Chinese cuisine — an indication of the low estimation many Chinese Americans held chop suey during the post-war years.

Chop suey is still an important dish in China

The rise and fall of Chinese American chop suey have had little impact on the prominence of numerous regional chop suey dishes in China. In fact, chop suey remains as important as it always has been and continues to be made from traditional ingredients including offal.

The Michelin Guide suggests traveling to the Anhui Province to experience a fantastic-tasting chop suey. This regional version of the dish spotlights fresh ingredients and uses large quantities of local colza oil for frying. Of course, another area to visit is the Guangdong Province: the place where America's version of chop suey originated. The cuisine of this area has changed over the years, meaning untraditional ingredients such as potatoes may be included in chop suey. That being said, this province still has a strong culinary association with offal, ensuring Guangdong's chop suey retains its iconic flavor profile.

Many chefs are reclaiming chop suey

Chop suey has yet to regain the notoriety it enjoyed in the early part of the 20th century. Yet, there are some chefs who are beginning to reincorporate the dish into their menus. Among the most prominent of these is Brandon Jew. He spoke to the Center for Asian American Media about how chop suey fits into his restaurant, Mister Jiu's: "So my creative process usually starts with an idea that's either based on recreating a historic dish or showcasing an ingredient. Then it's just testing it until I'm happy with it, until my sous chefs are happy with it, and then we figure out how to make 40 or 50 of them a night. It really starts with the ingredient for me. There are just some classic things we want to reinterpret. ... Chop suey just doesn't have really any recipe to it. We're taking the creative freedom to do our version of that, or even something like egg foo young."

Of course, many less well-known chefs — those who cater to towns rather than cities — also cook chop suey. In these instances, the chef is not so much reclaiming chop suey as a Chinese dish but celebrating a nostalgic, uniquely Chinese American one. The fact that the same dish wields so much duality in America is perhaps the defining feature of chop suey, one that ensures the dish's relevance for years to come.