Spurning The Common Wisdom To Make $225 Texas Wine

He believes that the traditional view of "terroir" — the aggregation of environmental factors believed to affect the characteristics of grapes, and thus of the wine made from them — in the popular wine press is "on its last legs." He has said that its defense rests more on vested interests than on sound science. He doesn't expect it to die without a bitter fight, but expects that the truth will eventually prevail.

The terroir revisionist is Dan Gatlin, the owner, grapegrower, and winemaker of Inwood Estate Vineyards in Fredericksburg, Texas. Not expecting people to believe someone who just talks the talk, he has also walked the walk — most recently in the form of two examples of chardonnay from grapes from two vineyards in Dallas County. His 2014 Dallas County and 2014 City of Dallas chardonnays are stylish enological near-doppelgängers for premier cru Chablis — despite being produced from grapes grown in a climate of 6,000 degree days (thermal units measuring heat accumulation, used to predict plant development rates) versus 2,200 in the Chablis region.

This isn't an isolated example. In 2002, two new cabernet sauvignon clones from France, touted to be of superior character, came to the U.S. It took about 10 years for the University of California at Davis's Foundation Plant Services, the American clearinghouse for imported grapevines, to certify them as disease-free. After that, the original material was released to nurseries, and Inwood was fortunate to get some vines in 2014. They planted them near Fredericksburg, in the Texas Hill Country AVA.

In 2015, they got only a smattering of fruit from these blocks, but he wasn't disappointed in it. He says: "In due time, I will release more detailed information about this work, but for now I can say that the difference in the DNA of various mutations, or clones, is so dramatic, it's hard to believe they are the same variety. We had already observed this with the Clone 4 cabernet at The Vineyard at Florence, and it revolutionized the way we thought about almost everything we were doing previously".

Who is this 35-year veteran of viticulture and enology, and what inspires him to send out literary tracts that rail against the status quo to his mailing list, in the tradition of nineteenth-century pamphleteers? I sat down with him not long ago to find out more.

But first, a little background. I discovered Inwood Estates Vineyards by accident. While I was attending a Bordeaux wine tasting at a wine store in Dallas in the late aughts, a friend virtually kidnapped me, bundling me into the back of his SUV while insisting that there was something I had to try. After a quick one-mile drive, we stood at a dowdy commercial unit on an industrial estate. He marched me to a tasting counter. There I was given two glasses. One was filled with Inwood Estates Vineyards 2005 Cornelius, a 100-percent tempranillo made from grapes grown at Newsom Vineyards in the Texas High Plains, the other with 2003 Bodegas Muga Reserva from Spain's legendary Rioja region.

I sniffed each, and I tasted each, and I was, as they say, blown away. While exhibiting stylistic differences (more ripeness for one), the Inwood stood toe-to-toe with the Muga in clarity of fruit expression, structure, intensity, and even finesse. Here was a compelling product demonstration to give to the taster who acknowledged facts rather than just drank labels.

This event would turn out to be the catalyst for my interest in Texas wines. Since then, I have watched the state's wines improve beyond all expectations, with Inwood Estates Vineyards as a leader in the evolution.

That day was also my first encounter with Dan Gatlin, who struck me immediately as interesting — an independent thinker and a winemaker of high standards. Gatlin grew up in the wine business. His father, an entrepreneur, founded a chain of liquor and convenience stores and Gatlin started his professional life as a buyer for the wine division. His job involved frequent trips to France and California. When his father sold the business, Dan had a chance to think about what he wanted to do. He could have gone to California but decided instead to plant a vineyard in Denton, just north of Dallas, with 22 vinifera grape varieties, to see what grew best. Before planting, he made sure he got the best viticultural advice available by travelling to the University of California at Davis and speaking with their experts.

I asked him about the results. "Unfortunately," he told me, "everything I was told, and ultimately implemented, was categorically wrong. Wrong vine spacing, wrong vineyard orientation, wrong trellis design (very important), and too many other wrong design features that were built into that first vineyard caused its ultimate demise. It was cheaper to start over and do it correctly than to retrofit the first project. I also got a quadruple dose of mundane vineyard maintenance since the poor design encouraged weed growth of geometric proportions. In summary, I learned everything not to do." After 16 years, he sold the property, and the vineyard is no more.

Gatlin's second vineyard was more modest. He planted it in the back garden of his house on Inwood Road in Dallas. Its significance, other than providing inspiration for the winery's name, is that it is the present-day source for the grapes that go into the wine he labels City of Dallas. Gatlin has long since sold the house, but its present owner is very happy for the vineyard to stay. The vineyard contains a few vines of tempranillo and palomino that he planted in 1997, but, he explains, "Today it's mostly chardonnay and cabernet." Chardonnay is in the majority, and that's the only wine he markets from the property. "The cabs are experimental," he explains, "and are eventually merged into other cabernet rather than marketed separately." Dijon clones influence the City of Dallas chardonnay greatly, he adds. "The lemon citrus comes through in large proportions compared to the green apple essence of the Dallas County wines, all Clone 4."

He continues, "Chardonnay is very underestimated in Texas, as we all know. However, the other side to the story is that it is extremely hard to grow well. It requires a great deal of experience in the school of hard knocks and a high degree of expertise. I often see the perfect harvest window for the season come and go within 20 hours. It's easy to see why so many people get frustrated with it. The margin for error is so small."

Nowadays, it is commonly accepted that tempranillo does well in the Texas High Plains AVA. Only a few people realize that Gatlin (along with grower Neal Newsom) was responsible for that. Fewer still know that it was an accident. Gatlin takes up the story: "After 16 years in the Denton vineyard, I was perplexed. I thought I had done everything right. I had consulted with the wizards of smart. I had executed their design. I had banked on 22 vinifera varieties in order to ensure success of at least one or two. I had worked myself silly. I spent obscene amounts of money.

"But something was wrong. The vines grew just fine and were healthy. But the chemistry was off. Now, even most knowledgeable people will assume I am talking about sugar, acids, and pH. No, the problem was much more complicated. I had great sugars; acids and even pH was acceptable to even sometimes excellent. The problem was that the wines had no flavor.

"My knee-jerk assumption was that if something's wrong, it must be wrong with the place. That's what the famous vineyards have told us for 150 years, right? The one bright spot in the early vineyard had been Spanish and Portuguese varieties. I reasoned that if somehow I could just get these vines, especially tempranillo, to a cooler climate, surely they would work."

Gatlin tried the Davis Mountains AVA but the 6,200-foot elevation was too prone to frost. He got three good vintages out of 20 years of ownership. The next step was to find something lower and flatter. He headed to the Texas High Plains AVA. He tried growers in Terry County, and saw some improvement in flavor relative to Denton. He moved on to Yoakum County around 1997 or 1998, at a slightly higher elevation. There, he ran into Neal Newsom. "We are both very intense and opinionated about what we do, so we had a lot in common," Gatlin says. "I subsequently began sampling from Neal's operation and noticed a very significant increase in quality. I was going to work in Yoakum County somehow, some kind of way. I had found what I was looking for, but I still didn't understand what made it work. Now I do."

What does he mean? "Before I go any farther with the story," he replies, "I want to deliver the moral, the lesson. Let me be as clear and unequivocal as possible: the reason Newsom fruit is as good as it is has nothing to do with the Newsom farm(s) or anything related to their place. It is 100 percent attributable to Neal and his skillset and commitment. Neal is too humble to say it, so I will say it for him: He is one of the best farmers anywhere, in any crop. His expertise and never-say-die-or-compromise attitude is what makes Newsom fruit the best. For those who are still having trouble with my anti-terroirist, contrarian perspective, let me describe it this way. Why do people pay so much more for [Burgundy's] Comtes Lafon or Faiveley wines than Drouhin or Jadot? They both make wines from many of the same vineyards. But you will pay a hefty increase in price for the first two for sure. The man in the street thinks there is something magical or mystical about the vines of the expensive producers. Nonsense. You are paying for their expertise and commitment to quality."

At the time, Gatlin attributed the quality of the Yoakum County fruit to the diurnal range in the High Plains versus that in the lower elevations of northern Texas. I remember him telling me that the cool nights allowed the fruit to reach physiological ripeness before the daytime temperatures sent the sugars up too much.

"I approached Neal with the idea of growing tempranillo," says Gatlin. "He refused — had never heard of it and told me flatly that he had no market for it if I went belly up someday. I proceeded to isolate two tracts that I was interested in purchasing for vineyards close to Neal. He first thought that I would bring the cuttings from Dallas, and objected strongly since he feared I would bring Pierce's disease into his area. Over months, I assured him I would not bring cuttings from Dallas, but that I would buy them new from a nursery in California. He expressed his further objections to the nursery I had always used, as he did not feel like their diligence in disease control was rigorous enough. Some more time passed and he decided that it was in his best interest to grow the fruit so that he could exercise control over the vinestock coming into his area. To mitigate the risk over tempranillo, I agreed to pay. The first viable, commercial tempranillo block in West Texas was born." High Plains tempranillo is now sold by more Texas wineries than any other red variety. Many may be blithely unaware of how the grape became a safe bet in the region.

Next, a side project took Gatlin in a new direction. A real estate developer working on a luxury home development in Florence, Texas (just north of the Texas Hill Country AVA), planned a vineyard as the centerpiece of the project, rather than the usual golf course. He contacted Gatlin about managing it and making the wine. The two parties struck a deal to move most Inwood Estates winemaking to a new facility on the development adjacent to the Vineyard at Florence winery. One legacy issue was that the vineyard was already planted, restricting Gatlin's freedom of grape choice. Most of the acreage was the French-American hybrid blanc du bois, widespread in those parts of Texas susceptible to Pierce's disease and normally producing pedestrian sweet or dry white wines. Also planted was the Lenoir hybrid, the Texas red grape resistant to Pierce's disease. It had been successfully made into good dessert wine but lacked pedigree for table wine.

Gatlin had always steered clear of hybrids in favor of vinifera grapes, but he approached the challenge at The Vineyard at Florence with the same deconstructionist rigor that he had his vinifera experiments. He wanted a dry wine, but not the foxy and forgettable sauvignon blanc wannabe that had been made elsewhere. With careful work in the vineyard and later picking he emerged with two original expressions of blanc du bois, which he called Aura and Aurelia, that presented themselves as more like Rhône white wines. The Rhône wines, full of flavors of tropical fruit, are typically blended from some combination of viognier, marsanne, roussanne, and grenache blanc. Gatlin made his wines in the same way the Rhône producers do, except for the fact that the Aurelia underwent full malolactic fermentation. At about twice the price of other dry blanc du bois wines, they sold out.

Gatlin also recognized a new marketing phenomenon occurring in Texas. U.S. 290 between Fredericksburg and Johnson City was becoming the Texas equivalent of Napa's Route 29 (2014 government figures placed it as the second most visited wine trail in the country, after Napa's). The traffic was fed mainly by nearby Austin and San Antonio. If you were a Texas winemaker and wanted to sell directly to your customer, the 290 wine trail was the place to be. In 2013, after a 20-month renovation, Inwood Estates Fredericksburg winery opened to the public on a key stretch of the highway. A far cry from the industrial unit in Dallas where I had originally tasted Inwood wine, it had a Napa-quality tasting room and a restaurant as well.

In 2005 and 2006, Gatlin experienced the first full El Niño cycle in West Texas — a long and then a short growing season came back-to-back. The terroirist theory predicted that this would produce drastically different wines. By adjusting to the weather and producing very low yields, Gatlin was actually able to produce wines of very similar quality each year. Only the size of the harvest differed. This planted the seed in Gatlin's mind of a different perspective on grape growing. "The proper view of a vine was not a plant influenced by its place," he came to believe, "which study after study was showing to be immaterial, and/or inconclusive at best. But, rather, the proper view was the physiological view that a vine is a mother producing offspring. Her berries are, in fact, her babies, and serve the beyond-ancient purpose of generational reproduction.

Therefore, the math was simple: If she has many mouths to feed (many berries), her nutrition is divided many ways; if she has a small population to feed, her nutrition is applied to a small output and polyphenols (chemical compounds affecting the flavor and aroma of wine) rise at a parabolic rate."

Thus, he believes, lower yields are key to the quality of the final output. He adds: "This alone accounts for Napa 2015 making a world-class wine, albeit in an unorthodox method (for them): Crops down 50 percent meant grapes off the vine in September with no decrease in their usual phenol counts."

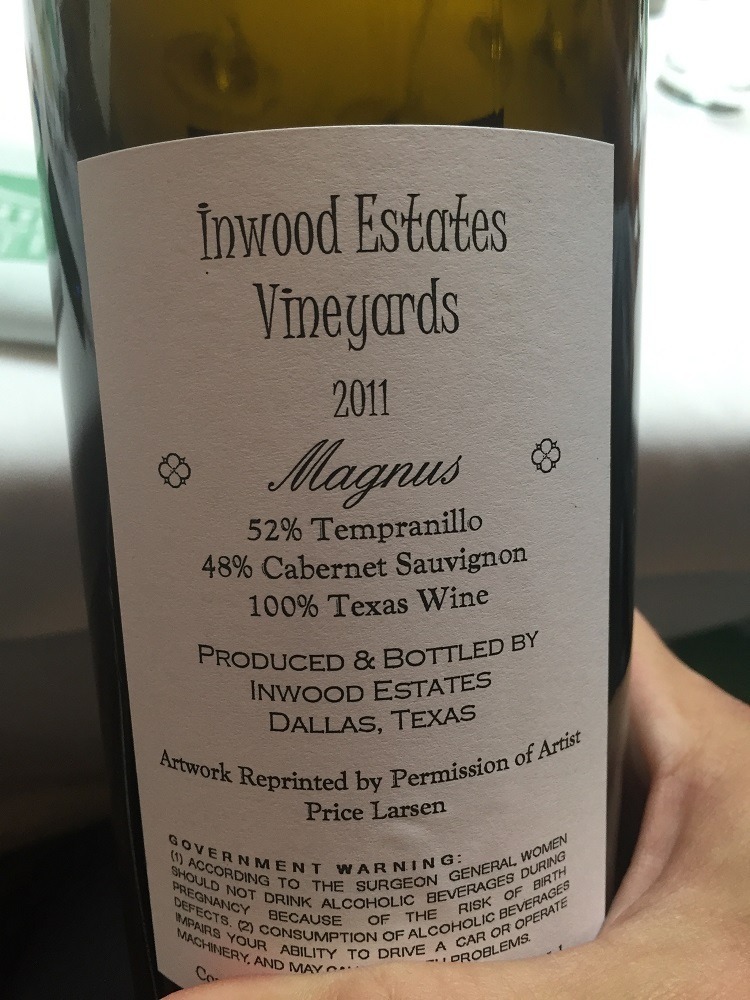

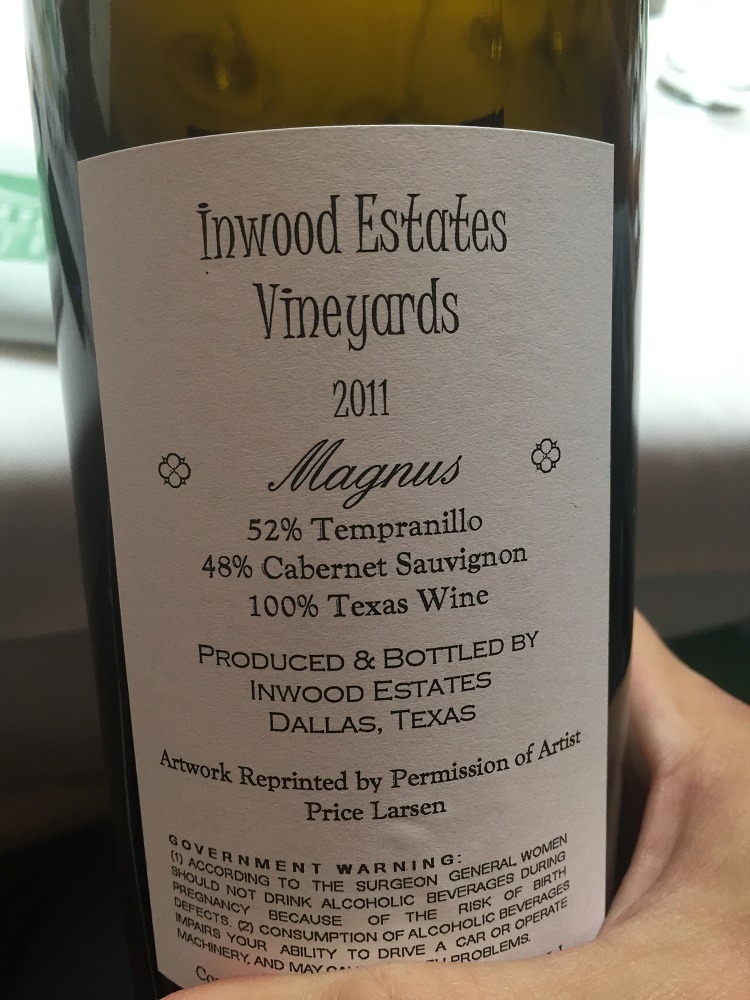

He put this theory to the test from 2008 to 2011 by working on two extraordinarily low-yield wines. His 2011 Magnus was a blend of cabernet sauvignon and tempranillo, while the 2011 Colos was 100 percent tempranillo. The wines shared a budget-busting yield of only 0.29 tons per acre (the Hill Country average for tempranillo is 1.9 tons), with a price tag of over $225 a bottle. Gatlin considers them the best wines that he has ever made, and uses them for mind-changing demonstrations similar to the one I experienced years ago, tasting them against the world-class wines that he aspires to better — Magnus against Vega Sicilia's Valbuena 5º from the Ribera del Duero and Colos against Numanthia Termanthia from Toro. Visitors to the 290 tasting room are offered the chance to sample this "super flight" every weekend.

Everything Gatlin has produced since his epiphany is based on his new beliefs. "Chardonnay in Dallas County that tastes like grand cru Chablis," he says, "and cabernet and tempranillo with fruit-juicy Napa-esque textures and colors. Is there any limit? No. When combined with the other eight to 10 critical yet modern parameters and precision execution of every minute detail during the growing season, anything is possible. Some of those things are correct vineyard design and orientation, modern trellising with high verticality, doggedly persistent canopy management, and high-tech irrigation monitoring and distribution, not to mention critically important selection of clones, and the list goes on."

On the economics of micro-yields Gatlin says "Is all this economically possible? Well that's a different question. I never promise riches, only great wine. Fortunately, there are a lot of highly educated wine collectors and aficionados out there now who see the value of where all this is headed."

Inwood's prices are higher than ever today, and the highest in Texas. Yet, Gatlin notes that demand for his wines is higher than ever, too. "Our Wine Club consumes a large portion of everything we make," he says, "and will soon consume everything. Our contact list extends into almost every major city in the U.S. We no longer accept restaurant and retail accounts. We are convinced we are on the right path."

Dan Gatlin is acting like a man who is just getting started. What next, Texas pinot noir?