2016 Winery Of The Year: Marchesi Antinori

It's safe to say that there is no better place in the world for wine-lovers than the good old U.S. of A. We have access to a broader array of wines — at every price level, from every corner of the winemaking world — than any other nation. The wines of Italy, France, Germany, Spain, and California, from world-renowned trophy bottles to lesser-known bargains with funny names, crowd our wine shop shelves and restaurant wine lists. Our supermarkets — in our more enlightened states, at any rate — offer aisles upon aisles of pinot grigio, sauvignon blanc, chardonnay, merlot, cabernet sauvignon, and more from Chile, Argentina, Australia, and New Zealand, and the exotically named grüner veltliner from Austria has become practically a commonplace. The adventurous can sniff out bottles from Moldova and Croatia, Lebanon and Turkey, Switzerland and Luxembourg, Mexico and India and Japan. Then there's our own wealth of wine, not just from the major players — California, Oregon, Washington, and New York — but from Virginia, Michigan, Idaho, Texas, and literally every other state in the union (though Alaska's wines are admittedly made with juice from elsewhere).

What all this adds up to is that in America we have the chance to sample wines bearing thousands upon thousands of different labels, wines made from hundreds of different grapes both famous and obscure, wines priced from almost nothing (hello, Three-Buck Chuck) to thousands of dollars. Nobody knows exactly how many wineries or wine-producing entities there are around the world, but some estimates put the number as high as 2 million. That may or may not be in the right ballpark — but there are more than 900,000 designated vineyards in Italy alone (not every one corresponding to a winery, of course, though many of them do) and about 28,000 actual wineries in France. Even the U.S., which is new to winemaking compared to our European counterparts, has at least 8,000 commercial wine-producers, and probably more. That's an immense number of producers to try to get a handle on, but try we have.

In early 2015, for the first time, we honored a Winery of the Year. The idea was to celebrate one wine producer from anywhere in the world that has produced consistently fine wines over a substantial period of time but has also served as an innovator and/or inspiration in the world of wine, whether dynamically or simply by example.

To arrive at our selections, we asked a panel of wine writers and bloggers (including our own regular wine contributors), sommeliers and wine merchants, and wine-savvy chefs to offer us their nominations for this honor. Our winner the first time we essayed this competition was not the newest, most obscure favorite of America's coolest wine stewards, but the Napa Valley's 1971-vintage Smith-Madrone Vineyards & Winery, known primarily for its exemplary cabernet sauvignon and unexpectedly sophisticated riesling. Last year, the honor went to another Californian, Tablas Creek — a leader in the propagation and use of Rhône varietals in California and an eloquent champion of viticological diversity and sustainable vineyard practices in the Paso Robles region.

As proud as we are of California wines, of course, we've never intended to celebrate only the wineries of the Golden State. As we've done in the past, we stressed to our panelists this year that the whole wide world of wine is open for consideration. Indeed, while California was still well-represented among the nominees this time around, we also received strong entries from Italy, Portugal, Spain, France (for whatever reasons, Alsace was particularly well-represented this year), New Zealand, England (for one of its best sparkling wine producers), Washington, Texas, and... Vermont. The last of these, proposed by wine writer and editor Susan Gordon, was La Garagista in Barnard, a high-altitude property making wines from biodynamically farmed French-American hybrids such as marquete, frontenac noir, and frontenac blanc. "Their focus," Gordon wrote, "is on establishing Vermont as a state with a viticultural identity and so responsibility, quality, and tipicity are mainstays." La Garagista was a real longshot this year considering the competition, but one of these years — who knows?

In addition to Gordon, special thanks are due, among our many panelists, to our regular wine (etc.) contributors Roger Morris, Andrew Chalk, Gabe Sasso, Summer Whitford, Steve Mirsky, Stacy Slinkard, and Rashmi Primlani, as well as Sacramento wine merchant extraordinaire Darrell Corti (a member of The Daily Meal Council), and wine writer, consultant, and teacher Guna Freivalde.

This year's finalists were a varied group, as we had hoped they'd be: Alois Lageder from Italy's Alto Adige; Aragonesas, the garnatxa specialist from Campo de Borja in Spain's Aragón region; Sacha Lichine's Provençal rosé powerhouse Château d'Esclans; Charles Smith Wines (also a finalist last year) and Château Ste. Michelle, both from Washington State; Central Coast cabernet specialist DAOU; the superb Alsatian producer Domaine Zind-Humbrecht; Herdade do Esporaõ, which produces standout Portuguese wines in both Alentejo and the Douro; Marchesi Antinori from Tuscany and beyond; Masciarelli from the Abruzzo in central Italy; and the Napa Valley's classic Shafer Vineyards.

The votes were counted and our panelists' comments considered; here, then, are our two runners-up and our Winery of the Year for 2016:

Honorable Mention: Domaine Zind-Humbrecht

The Humbrecht family has farmed vineyards in Alsace since the early seventeenth century, but Domaine Zind-Humbrecht dates only from 1959. In its 50-plus years, however, it has established an unshakable reputation as one of this underrated and often misunderstood French wine region's best and most consistent producers. Its wines include examples of all the major Alsatian varieties — above all riesling and gewürztraminer but also pinot gris, pinot blanc, muscat, and pinot noir, all estate-bottled — and all are in the top rank. The examples sourced from the winery's grand cru vineyard holdings — Rangen, Brand, Hengst, and Goldert — are especially noteworthy. (Anyone interested in experiencing great riesling that doesn't come from Germany is hereby referred to Zind-Humbrecht's 2014 Rangen de Than Clos Saint Urbain, wonderfully intense in flavor but elegant and austere in structure with a bright mineral edge.) The winery has been a modern-day leader in the use of biodynamic vineyard practices in Alsace, and has intentionally reduced yields in order to produce wines that are particularly opulent, intense with fruit, and often softened with residual sugar, even in wine styles where it wouldn't be expected. Beginning with the 2001 vintage, Zind-Humbrecht also introduced an unofficial labeling device, designating each wine's level of sweetness with an "indice" (index) rating of 1 to 5, meaning dry (or nearly so, in the typical Alsatian style) to very rich and sweet. As one of our panelists, David Sawyer, former wine director at Husk in Charleston, South Carolina, puts it, "Ploughing the vineyards with horses, using cover crops, and allowing long natural ferments, leaving the wines on their lees until they're ready, this iconic Alsatian producer makes insanely delicious wines that cover a myriad of food pairing options. Olivier Humbrecht and his father Léonard are not just talking the talk, but walking the walk!"

Honorable Mention: Château Ste. Michelle

Way back in 1954, when nobody had ever heard of Quilceda Creek or Woodward Canyon or Cayuse or any of Washington State's other top-flight contemporary wine producers (because they were all still decades away from being born) — when, for that matter, the idea that the state could actually produce grape wine worth drinking sounded like a joke — a couple of small operations making fruit wines, the Pomerelle Co. and the National Wine Co. merged to form American Wine Growers. AWG evolved into Ste. Michelle Vintners and the Château Ste. Michelle, and with the help of legendary Napa Valley winemaker André Tchelistcheff as consultant, began producing high-quality wines from cabernet sauvignon, riesling, and other noble grapes. Along with Associated Vintners (now the Columbia Winery), Ste. Michelle can truly be said to have pioneered fine wine in Washington, and it grew large enough and marketed its wares so widely that it almost single-handedly established the state's reputation for wine excellence. (Today, Washington is the third-largest wine-producing state in America, after California and New York.) Along the way, the winery has developed new vineyard areas, introduced new technology, maintained high standards of production, trained winemakers who have gone off on their own to great acclaim, and just in general been an industry leader in Washington and beyond. From their accessibly priced Columbia Valley and Indian Wells lines (the $15 Columbia Valley Syrah is one of America's great red wine bargains) to their top-of-the-line Artist Series Bordeaux-inspired blends, Château Ste. Michelle keeps doing it right.

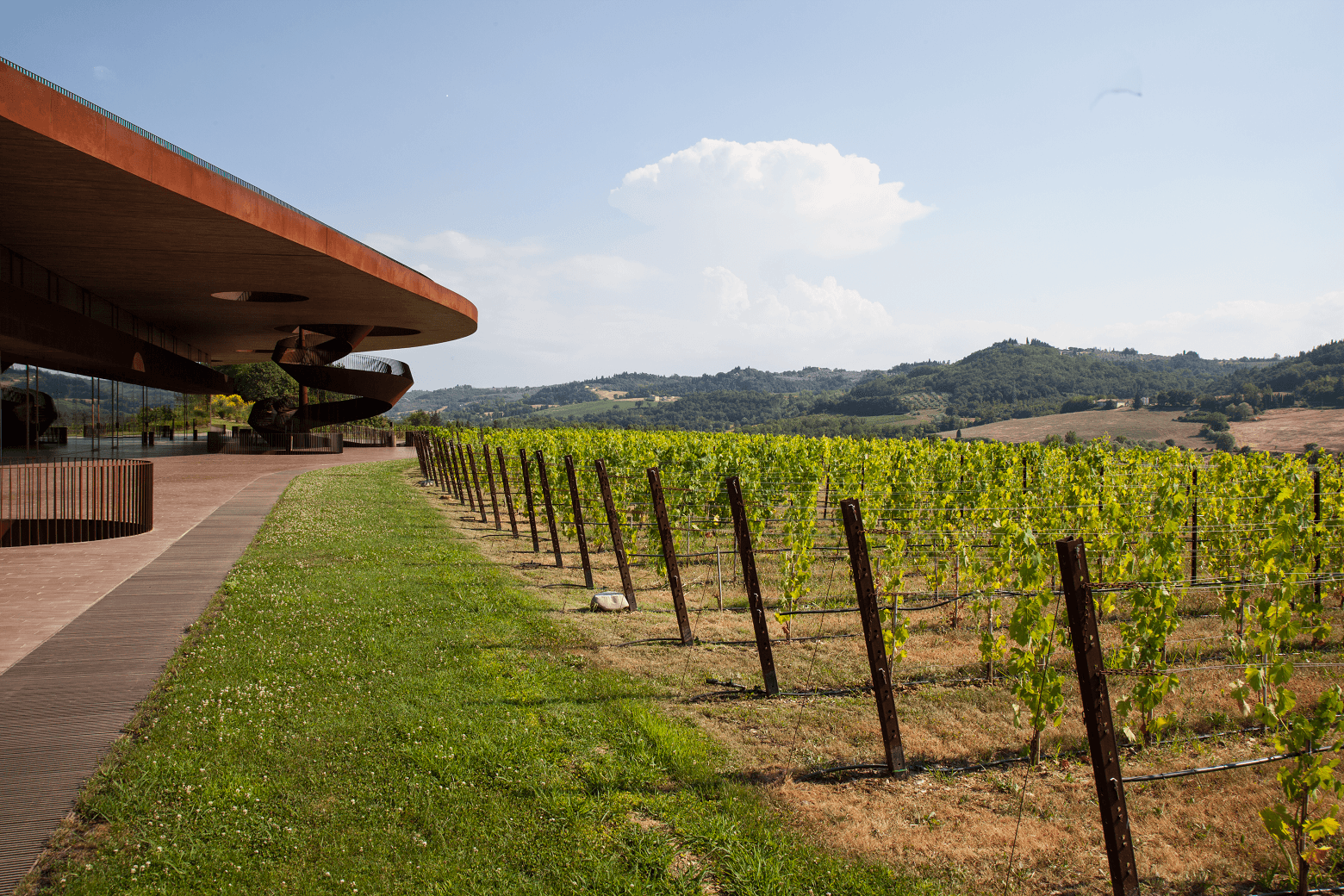

Winery of the Year: Marchesi Antinori

Decades ago, at the huge international wine fair called Vinitaly, held annually in Verona, I was standing in line for admission to a tasting of new Antinori vintages to be conducted by the estimable Piero Antinori himself. Just behind me in line was a novice wine writer who has since become a highly knowledgeable major figure in wine journalism. He leaned over to me and asked me, sotto voce, "Now, is Antinori an area or a grape variety?" It is hard to imagine even a vinicological tyro making that mistake today.

The Antinori family can trace its Tuscan winemaking roots back to 1180, and various Antinoris have been prominent in both winemaking and Tuscan political and financial life ever since. In the early 1920s, Niccolò Antinori blended a small quantity of cabernet sauvignon into his Chianti — the official "recipe" for the wine, devised by the Barone di Ricasoli in the mid-1800s, allowed for 5 percent "other" varieties along with the prescribed 70 percent sangiovese, 15 percent canaiolo, and 10 percent malvasia — and his son, Piero, later took the idea and ran with it: In 1971, Piero launched a red wine named after his vineyard at Tignanello, containing cabernet sauvignon and cabernet franc as well as sangiovese. It was not eligible to be called "Chianti" and could be labeled only "Toscana" — but it revolutionized this corner of the Italian wine industry. It wasn't technically the first "super-Tuscan" — Piero's uncle, the Marchese Incisa della Rocchetta, bottled high-quality cabernet sauvignon at his Sassicaia estate, first releasing it commercially in 1968 — but it was Tignanello that popularized the idea, led to a change in official Chianti recipe, and inspired literally hundreds of other producers to extend the possibilities of Tuscan red wine. It remains a great red wine to this day.

Antinori's importance is by no means only historical. Piero introduced scores of innovations to the Tuscan wine scene, from vineyard to barrel room to bottling line. And with a host of first-rate Tuscan bottlings, under labels including Solaia (arguably the most elegant Tuscan expression of cabernet sauvignon), Badia a Passignano, Pèppoli, Guado al Tasso, La Braccesca, Monteloro, Fattoria Aldobrandesca, and Pian delle Vigne, as well as the popular Castello della Sala line from neighboring Umbria, Antinori is one of the most important, influential, and dependable wine producers in Italy. (The family also has a Napa Valley property, now called Antica Napa Valley; and Col Solare, a property in Washington State in partnership with the aforementioned Château Ste. Michelle.) As Darrell Corti puts it, Antinori — now under the direction of Piero's daughters, Alessia, Albiera, and Allegra — deserves this honor "for its lead in changing the face of Tuscan and then overall Italian viticulture and enology — and for producing wines that are very good to excellent at reasonable prices."