Baby Food: What Can We Learn From Those Little Glass Jars?

There's so much more to eating than just food. In her new book, Inventing Baby Food: Taste, Health, and the Industrialization of the American Diet, Dr. Amy Bentley says that eating food is a social activity, full of meaning; "Not only what we eat, but how and why we eat, tell us much about society, history, cultural change, and humans' views of themselves," and baby food is no exception.

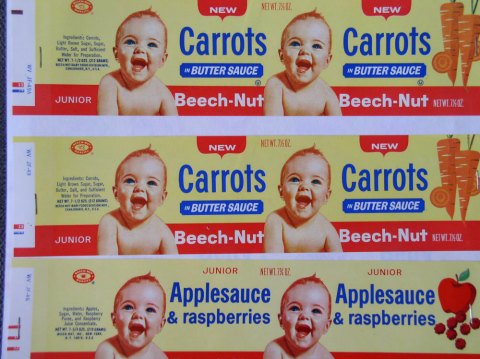

Her book traces the history of commercial baby food, linking it to Americans' taste for the highly processed foods that wreak havoc on our health and to our changing ideas about what it means to be a good mother (or parent in general). Basically, when we offer babies a narrow range of foods at such a young age, we teach them that that is what food should look, taste, and feel like. The foods we choose to feed our babies become intertwined with our success (or failure) as parents.

(Credit: 'Inventing Baby Food')

This thought-provoking historical work will not only make you rethink your food choices (and the tradeoffs we make each day), but it will also give you hope for the future of commercially prepared food.

We had the opportunity to talk with Dr. Amy Bentley about her new book and about baby food. Here's what she had to say:

There's a lot of talk right now about when and how eating preferences are formed. In your book you draw a connection between the creation of commercial baby food and America's industrialized palate. What role did/does baby food play in shaping food preference?

So, just to back up a little bit, we know that humans are hard-wired to have certain preferences and aversions. We have a preference for sweetness (because of the sugar in breast milk) and a natural aversion to bitterness, for example. [pullquote:left]Part of what I am saying in the book is that, in the mid-twentieth century, commercial baby food became the normal way that infants were fed (90 percent were fed food from commercial manufacturers) and that commercial baby food was like other industrial food products: it contained sugar, salt, preservatives, and starches. There was an assumption that it didn't need to be made any differently, that it was sterile, scientific, and better than you could make at home. So, as soon as six to eight weeks after birth, infants started receiving these highly industrialized products, which further increased their preference for sweet and salty flavors. I argue that this primes their palate further, that it narrows the range of flavors, tastes, and textures that they're receiving.

(Credit: 'Inventing Baby Food')

What does science say? Is there evidence to support the early formation of food preference?

It's never a one-to-one correlation (humans are complicated and there are a variety of cultural factors that affect food preference), but yes. We know that babies learn a lot through taste. Amniotic fluid has a taste, so babies are already learning in-utero.

Infants learn about food through texture and appearance as well. There was research done in England in which babies were fed all-white foods like rice cereal, applesauce, and bananas; they were taught that food is beige or white. It made it even more difficult for them to register bright colors. It was a study about color but is it any wonder that, when we feed babies this way, they move on to be more comfortable with pasta, rice, and French fries?

Your book also talks about the relationship between feeding and nurturing. Can you talk a little bit about how baby food has contributed to (and continues to contribute to) our changing notion of what it means to be a good parent?

Well, this is a theme that has existed for quite a while. And, it's part of our current culture. In the early twentieth century there was a proliferation of mass-produced goods; stuff was available to buy and a woman's role of purchasing food for the family comes intertwined with her role of nurturing them.

The idea still exists; part of being a good mother is purchasing the right products for your baby. The products have changed, the brands have changed, but the idea still exists. And baby food is by far the biggest category of these items. With so many foods and so many stages, there's a product for every age and demographic. Even if you're making your own baby food, there are grinders and tools and equipment.

(Credit: 'Inventing Baby Food')

What's the practical take-away here? What can today's parents lean from the history of commercial baby food and what should we focus on moving forward?

Baby food is a category of convenience for American families and for American women. It's been produced poorly and it's been produced better; this book shows that trajectory. It became popular (and continues to be popular) for this reason; it provides flexibility.

The take-away is that our food system is always a series of tradeoffs. Are we going to trade convenience for control? Do we sacrifice taste for flexibility? Time for homemade foods? We make tradeoffs in food all the time.

We have a huge, largely successful (but broken) food system; it's done a good job of providing a lot of food for people, but now we need to fix the system and make it better.

For more information on Dr. Amy Bentley or to purchase a copy of her book, 'Inventing Baby Food: Taste, Health, and the Industrialization of the American Diet' with a 30% discount, visit her website.

Kristie Collado is The Daily Meal's Cook Editor. Follow her on Twitter @KColladoCook.