10 Secrets Dairy Queen Isn't Telling You

Dairy Queen, the easily recognizable soft serve stop that offers cones with the signature — and trademarked — curl, has been around since 1940. Named because the original proprietor, J.F. McCullough, considered the cow to be "the queen of the dairy business," DQ soft serve can be found today at franchises in all but one U.S. state and across another 19 countries worldwide. Though the restaurant chain menus have been serving savory fast food since the 1950s, these items are secondary to the frozen treats. Dairy Queen remains most popular for the desserts on its menu, such as the classic vanilla soft serve, the beloved Dilly Bars, the renowned Blizzards, and even ice cream cakes.

In its many decades of operation, Dairy Queen has been around long enough to incite nostalgia from many consumers, but it has also survived quite a few causes for concern over the years, both from the standpoint of corporate advertising and in the complications that have arisen within individual franchises. The chain has been remarkably adept at quelling consumer distrust and disagreement when problems have arisen. In some cases, it's been able to simply keep things quiet, as it remains a popular fast-food go-to with a large and loyal fanbase that has been willing to forgive numerous indiscretions. From the inclusion of unexpected ingredients to an alarming number of health code violations, some of these secrets are closely guarded, some surprisingly unsavory, and some just plain hard to swallow. Here is a list of 10 of the biggest secrets DQ isn't telling you.

1. It's technically not ice cream

Ice cream has an important attribute that makes it creamy — its butterfat content. This is the naturally occurring fat in cow's milk that's used to make butter, and it's also an integral aspect of ice cream's texture, as it enhances creaminess. The percentage of butterfat differs depending on the quality of ice cream but, per the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), there are specific standards to follow: For a frozen dairy product to be considered ice cream, it must contain a minimum of 10% butterfat. Most traditional scooped hard serve ice creams contain 10-18%, but Dairy Queen's soft serve has a mere 5% butterfat. This means that Dairy Queen's specialty is not not ice cream, but by the legal definition, it's considered reduced fat or light ice cream.

DQ's specialty cones are officially called "soft serve," in which air content makes the difference, with more of it whipped in during the mixing process. As it turns out, Dairy Queen founder J.F. McCullough may have invented soft serve or, at least, was at least one of the first to sell it. He did so in 1938 at a friend's ice cream shop in Kankakee, Illinois. Two years later and one hour north, McCullough opened up the first Dairy Queen in Joliet, Illinois to sell his soft serve. The airy frozen treat was innovative for its time, and made Dairy Queen popular from the start.

2. You may never know the secret recipe

Back in 2010, Dairy Queen's former chief brand officer revealed that the official recipe for DQ's soft serve was top secret. This secret was taken so seriously that it was kept in a safe deposit box to which only a few keys had access. Despite recent calls for more transparency with nutrition information, it has remained possible for specific brand recipes to remain secrets, as fast food chains are simply required to disclose nutrition information for their food items (such as calories and fat content) but are not obligated to disclose a complete list of ingredients for their standard menu items.

Despite the secrecy, there's now a list of ingredients for the legendary vanilla soft serve available on DQ's website: Milkfat, nonfat milk, sugar, corn syrup, whey, mono and diglycerides, artificial flavor, guar gum, polysorbate 80, carrageenan, and vitamin A palmitate. Though the number of additives may seem alarming, they are required as emulsifiers. These compensate for the soft serve's low fat content, enabling it to hold its shape. Whether or not this is an exhaustive list of ingredients is not specified, but since the exact quantities of each are not known, the official recipe still remains more or less a mystery. The one secret DQ is open about revealing is the temperature at which it keeps its soft serve, which is an integral part of maintaining texture and flavor. The brand proudly declares this to be a chilly 18 F.

3. DQ's frozen treats have more sugar than you realize

With sweet treats being the most important item on the menu, Dairy Queen has never been a place for the health-conscious. Even so, the amount of sugar in DQ's desserts is shockingly high. The menu items with some of the lowest sugar content — a small DQ vanilla cone has 26 grams, a medium 36 — still max out or exceed the American Heart Association's recommended daily sugar intake for men and women, respectively. These soft-serve options also contain more than the average scooped hard-serve vanilla ice cream, which often has less than 20 grams of sugar per serving.

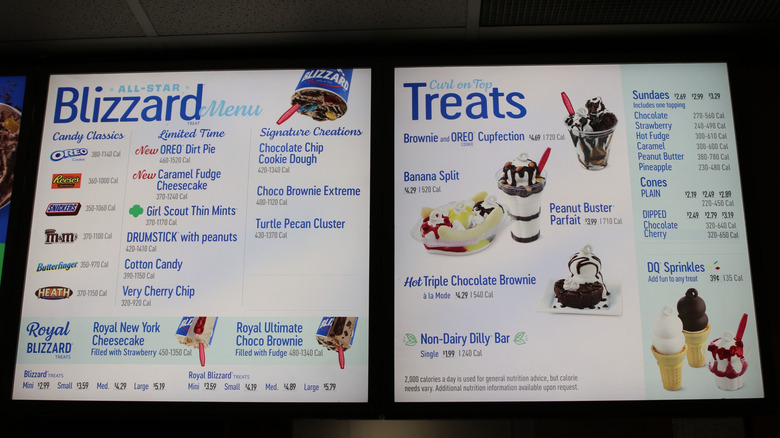

Beyond the classic vanilla cones, Dairy Queen shakes average between 60 to 128 grams of sugar, depending on the size and flavor, which is already a pretty steep amount. But it's the infamous Blizzards, with their candy mix-ins, which top the charts. Mini Blizzards, with their limited size, average around 40 grams of sugar, not much more than one of the classic cones. But the larger sizes quickly skyrocket in their sugar content, with many flavors in medium size and up containing well over 100 grams. The large M&M's Blizzard has the highest sugar content on the menu, totaling 159 grams. That's six times the recommended daily intake. Considering that consuming excessive added sugars contributes to health conditions including diabetes and heart disease, DQ treats are among those best enjoyed in moderation.

4. Some candy brands considered removing their products from blizzards

Dairy Queen Blizzards are a staple that's barely changed over the years, but they didn't become a point of major concern for their sugar content until 2016. This was when the candy brand Mars, manufacturer of Snickers, Milky Ways, and M&Ms, announced that it might pull its candies from fast food chains' beloved frozen treats, including Dairy Queen's Blizzards. This was a point of concern for many consumers, as the M&M's Blizzard is a favorite on the dessert menu. These threats in the name of promoting lower sugar intake, however, have quietly disappeared.

Despite being a candy company founded upon sugar consumption, Mars has surprised many with its reformed public stance on promoting reduced sugar intake. True to these updated policies, it's been a forerunner in sugar consciousness. It was the first U.S. candy brand to include sugar content on its packaging and even completely discontinued its king-size candy bars to limit the sugar and calorie intake for single servings. The brand's concern with Mars candies being mixed into fast food frozen treats came from the notion that these desserts no longer aligned with the brand's policies on added sugars, as candy add-ins make up about a third of the entire sugar content for such sweets. While Mars' concern seems to remain an empty threat, fast food restaurants have been required to include nutrition information for their menu staples since 2018, including sugar content.

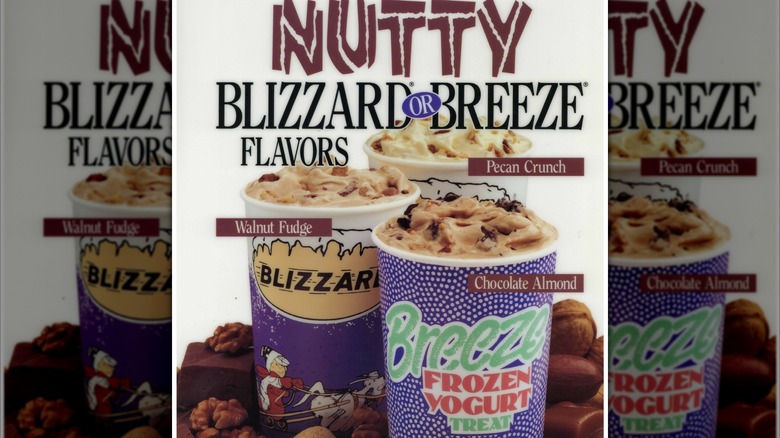

5. A more health-conscious dessert campaign failed

Dairy Queen has also tried to promote healthier desserts in the past, though with little success. The chain was a forerunner in offering low-fat frozen treats when it released the Breeze, a mostly-forgotten DQ dessert from the 1990s. The Breeze first came out in 1990, and was intended to be a low-calorie Blizzard made with frozen yogurt. Froyo is made from cultured milk rather than cream, so it has inherently less fat in its composition, making it a naturally lower-calorie dessert. This does not, however, necessarily make it a healthier alternative to soft serve or ice cream, as it contains many additives to help maintain its texture, and it's sweetened with plenty of sugar. In fact, frozen yogurt often contains more sugar than regular ice cream, which may be added to counteract the naturally more sour flavor that comes from the cultured milk.

Often still made with the same candy mix-ins, it's unlikely that DQ's Breeze frozen yogurt desserts were really a health-conscious alternative to Blizzards, even if they did have slightly fewer calories. Either way, the Breeze didn't appeal to consumers. It was removed from DQ menus in 2000, allegedly because the frozen yogurt was so rarely ordered that it often went bad before it could be served to customers. Despite being innovative for a fast food chain, the Breeze just wasn't popular, and hasn't returned to menus since.

6. Blizzards upside down are only possible at participating locations

The Blizzard, and its often inverted presentation, began with DQ chains in St. Louis, Missouri. The concept, however, borrowed from a gimmick at a local St. Louis frozen custard stand. There, Ted Drewes Frozen Custard had been selling its servings upside down for a few decades. Called "concrete," this ultra-thick custard didn't budge when upturned, and was a response to a teenage boy's persistence. Back in 1959, per Mental Floss, Steve Gamber was a daily customer at Drewes' stand, and always requested his frozen treats be thicker than the previous day's order. Drewes' concrete custard was the solution, and appealed to other customers too — enough that business was still booming even with fast food chains like DQ setting up shop nearby. When a local franchise owner saw the popularity of Drewes' serving method, he knew DQ could have success with the same concept and pitched the idea. In 1985, the Blizzard was born.

The upside-down factor has since been a Blizzard marketing tool, and customers are quick to remind the chain of its own policy: If an employee fails to serve an inverted Blizzard, then the next one is free. Unfortunately, many DQ fans have been disappointed to learn that this policy does not apply to all locations these days. It is up to franchise owners' discretion whether Blizzards be served upside down, as well as whether customers should get a free one if they don't witness the presentation of gravity-defying frozen treats.

7. Dilly bars aren't always made by hand

The Dilly Bar, another iconic DQ treat, got its start at a Dairy Queen location in Moorhead, Minnesota in 1955. It was an experiment that was unexpectedly — and wildly — successful. A circle of ice cream on a stick, dipped in chocolate, butterscotch, or cherry became a treat quickly adopted onto DQ menus nationwide, and the Dilly Bar remains a staple to this day. At the Moorhead location, Dilly Bars have always been made by hand. Once formed into circles with the iconic curl, they are kept in a freezer at an optimum temperature of -20 F, left to sit for six hours, and then hand-dipped in the chocolate, butterscotch, or cherry coating.

Other DQ locations that added the Dilly bar to their menu also used to prepare these treats by hand, but today many locations rely on pre-made Dilly Bars created specifically for DQ restaurants by a separate manufacturer. It's easy to tell which Dilly Bars are pre-made. Most notably, they're served in sealed plastic wrappers, and this includes the vegan Non-Dairy Dilly Bars made with a frozen dessert base of coconut cream. The classic made-in-store bars, on the other hand, are presented in a paper bag. Once opened, there's another obvious difference with machine-made Dilly Bars, as they disappointingly do not have the signature curl in the middle, since it's something that mass-manufacturing machinery can't replicate.

8. Some of DQ's advertising has been controversial

Though a chain with a large fanbase, DQ has had some controversial advertising ideas in the past that posed some concern, and one in particular involved one of DQ's many, short-lived mascots. Though customers are generally glad the cursed Curly the Clown is gone, it was another former mascot that posed more widespread controversy. Depicted either as a baby, a girl, or sometimes even a woman with dark hair and a parka, this mascot was called the "Eskimo baby" or "Eskimo girl," and presented a stereotype of indigenous people. While the imagery was problematic in itself, the nickname also encouraged the use of a word that has often been used in a derogatory context. Most locations have long since taken down these caricature mascots, but a few still remain. Dairy Queen claims not to stand by individual franchise owners' determination to keep these signs on display.

Another highly controversial incident was the introduction of DQ's MooLatte, a sweet, caffeinated confection of coffee and vanilla soft serve topped with whipped cream. Many people didn't understand how DQ could have accidentally named a beverage something so similar to the term "mulatto," used to refer to a person with mixed black and white ancestry. The coincidence was uncanny enough to leave many people suspicious, but this concern did not persist long enough to prompt Dairy Queen to officially change the name. The MooLatte remains a feature on DQ menus worldwide.

9. Many locations have been subject to scandal

With thousands of locations and over 80 years of operation, DQ restaurants have faced their fair share of scandal, although some instances have been nothing more than rumor, as was the case with a South Carolina location that faced an FBI raid in 2019. Though the reason for the raid had to do with a business running unlicensed money transfers, an unfounded and untraced rumor started circulating that this DQ location had attracted a federal investigation because "human meat" had been found in its burgers. The rumor was quickly disproven, but the continuing bad publicity pressured DQ to state outright that its hamburgers were made entirely from beef.

Another DQ scandal, sounding almost too unseemly to be true, was a more recent incident that occurred at a Kentucky Dairy Queen in 2024. There, employees reported that the manager had forced them to consume soft serve that was contaminated with chemicals. The reasoning behind this demand was not reported, but some of these employees who ate the contaminated soft serve ended up in the emergency room as a result, and the local sheriff's department quickly opened an official investigation into the matter. Yet another scandal occurred at DQ locations in Indiana and Michigan in 2022. These restaurants were charged with violating child labor laws, with employees aged 14-15 working longer than what's legally allowed, in a direct violation of the Fair Labor Standards Act.

10. DQ franchises are no stranger to health code violations

Between improper cleaning protocols and human error, an alarming number of health code violations have occurred in the rush of trying to attend to customers at certain busy DQ locations, and a few of the worst are particularly unsettling because of how lax the sanitary standards were. Though it has since passed a reinspection with flying colors, a location in Atlanta, Georgia failed a health inspection in 2016 for the mold that had built up in some of the equipment, grimy premises, and food storage at inadequate temperatures. All of this carelessness was going unaddressed until after these violations were brought to light.

That same year, a location in Santa Cruz, California was shut down twice by the local health department for a slew of health violations. In addition to mold discovered in both the soft serve machines and refrigerator, the restaurant had dirty Blizzard containers ready to offer customers. Even worse, shakes had been prepared with expired milk and there were cockroaches on the premises which came into contact with the food. Somehow even worse, in 2014, a Denver, Colorado Dairy Queen one-upped these violations by accidentally serving customers toxic treats laced with cleaning solution. This was the result of an oversight between employees — one worker hadn't realized a bucket in the sink was filled with cleaning chemicals, presumed it was clean, and used it to prepare vanilla syrup which was subsequently served to customers in their frozen desserts.