Whatever Happened To Swanson's Frozen TV Dinners?

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Humans have been freezing foods for ages, but Clarence Birdseye changed the game when he introduced the quick freezing method in 1924. This method, and the ensuing Birdseye company, helped push frozen vegetables into homes. By the early 1940s, the idea of dinners made of frozen foods was picking up steam, particularly with home cooks, who sought easier preparation methods. Then, in 1945, the company Maxson Food Systems packaged an entire frozen dinner for the American military, and soon did FrigiDinner as well. Not long after, in the 1950s, television took off, finding families eating in front of their sets. The Swanson company then seized this opportunity to launch the TV dinner.

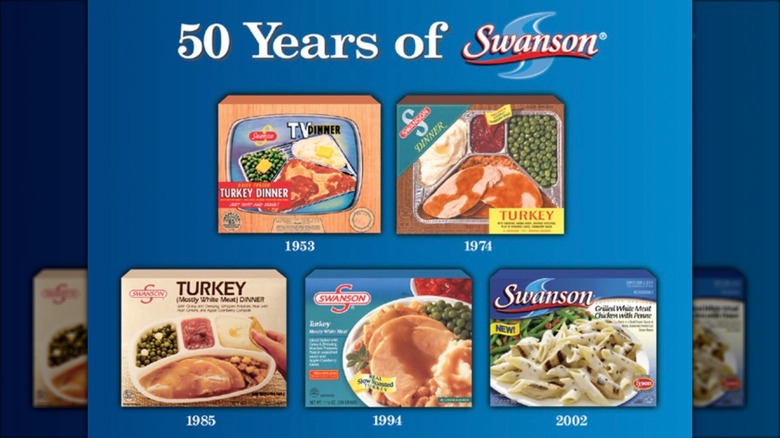

Swanson's original frozen TV dinner consisted of a compartmentalized metal tray, an entrée, and two sides — all for just 89 cents. In its first year on shelves, 10 million units were sold. In the following decades, the dinner adapted to changing diets and tastes. By 1987, 150 million units were being sold annually. Today, the company's dinner tray remains such a symbol of American culture that one is held at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

However, these meals aren't so popular anymore. As the 20th century came to a close, the frozen TV dinner fell out of fashion. While subsequent owners tried to breathe new life into Swanson and its dinners, they were unsuccessful. So, pull up a TV dinner tray, and let's examine the rise and fall of Swanson's frozen TV dinners.

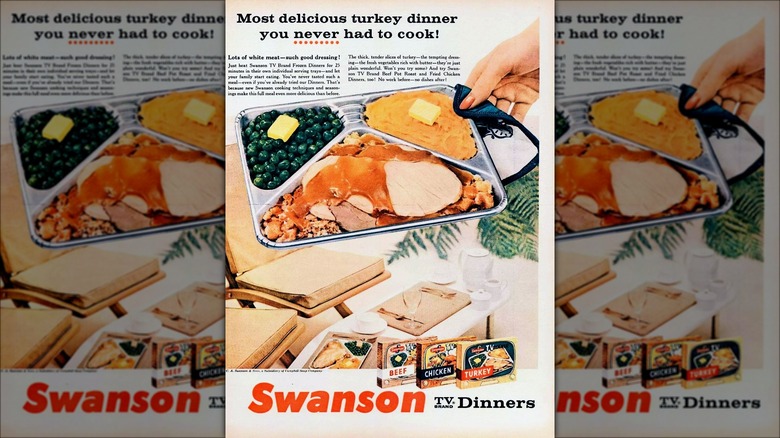

The company releases a turkey meal for its first TV dinner

There is a lot of confusion around who exactly invented Swanson's frozen TV dinner. Many think it was Gerry Thomas, who started working for Swanson in 1948. After an overly fruitful amount of turkeys were born, the company was left with a surplus of meat. Through his own research, Thomas found that mothers and children were gobbling up the company's frozen chicken pot pie while watching TV. He recalled to the Omaha World-Herald in 1996: "I thought they might also eat turkey if we added other foods and made it a complete dinner." He says he then suggested calling it a "TV dinner."

The product was developed by Swanson bacteriologist Betty Cronin, and home economist Carolyn Flanders, who supplied the original cornbread dressing recipe that accompanied the turkey slices, giblet gravy, and buttered peas and yams. The three-compartmented trays were originally supplied by a Nebraska wheelbarrow company, and the dinners were assembled by hand. The dinner tray was housed in a box that looked like it was within a television set.

Test markets for the new product included Florida, New Orleans, and the West Coast. The initial returns, which delivered an oven-cooked meal in 15 minutes, were so promising that the product launched nationwide. By the summer of 1954, fried chicken was introduced as a second entrée choice, and beef soon followed.

Swanson expands its frozen dinner line

In 1955, Swanson was acquired by the Campbell Soup Company, which helped to expand its reach, as well as keep competitors like Banquet at bay. As the 1960s began, a new advertising slogan was implemented, letting buyers know they could "Trust Swanson." This slogan appeared in ads that lasted the entire decade. In order to keep customers coming back for more TV dinners, Swanson launched additional frozen meal options.

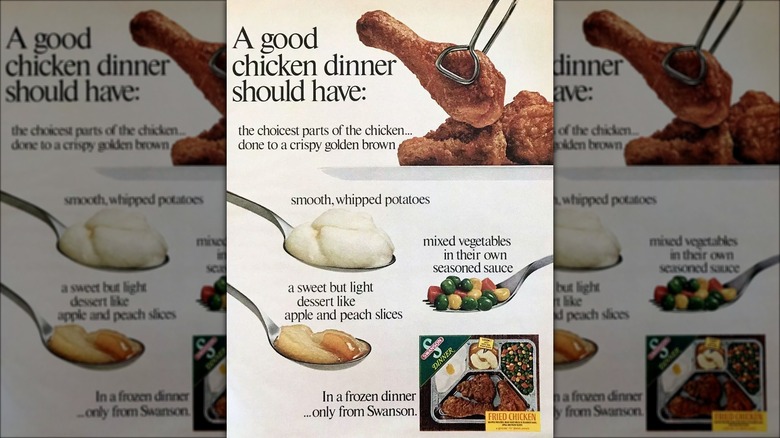

In 1960, new additions included dinners made of loin of pork, ham, macaroni and cheese, Swiss steak, and creamed chicken — with sides like French fries and sliced apples. A year later, fried shrimp — complete with cocktail sauce — was introduced, joining haddock and scallops. The possibilities seemed endless, and meals like franks and beans, spaghetti and meatballs, and corned beef hash soon joined the lineup. Then, in 1965, Swanson brought a taste of Germany, Italy, Mexico, and China to the American shores with a line of International Dinners. In the latter part of the decade, it would also introduce a smaller entrée line, which consisted of just meat and a single side.

The brand decides to rename its meals

Swanson had trademarked the term "TV dinner," but, like other popular products — such as aspirin, thermos, and cellophane — it became a generic trademark, meaning it was free for anyone to use. As the 1960s came to a close, Swanson didn't even want to use the term itself with its own dinners. It pulled the term "TV" from the product's name, and removed the TV set's frame imagery from the packaging, too. This was because the company was worried that the "TV" moniker was preventing the product from being eaten at any time of the day.

In the ensuing decades, eating dinner in front of the TV wasn't seen as a fun novelty anymore, but more of one of laziness. The Swanson brand continued to avoid such connotations with its core product. In 1989, Product Manager Joe Brennan told The Chicago Tribune: "We don't like to use the term TV dinners. We've moved away from that. People don't want to be considered couch potatoes."

Bigger appetites bring about the birth of Hungry-Man

In 1963, Swanson whetted customers' appetites even more, with the introduction of its 3 Course Dinner. The meal came with a portion of Campbell's soup, meat, whipped potatoes, a veggie, and a fruity dessert. In 1972, this idea was taken even further, and spun off into a new line called Hungry-Man. In early print ads, such as one from The Boston Globe, the appeal of large portions was spelled out in the copy: "If you've got a man who eats like there's no tomorrow, give him a Swanson 'Hungry-Man' frozen dinner tonight. Look! Not one — but two Salisbury Steaks in brown onion gravy. Swanson already put the second helping in." Turkey dinners had double the amount of meat, and fried chicken ones came with four pieces.

To further strengthen the masculine vibe, sports figures were drafted to appear in TV ads. Los Angeles Dodger greats Tommy Lasorda and Steve Garvey were shown eating them in the dugout. Then, in the 1970s, ads featured Pittsburgh Steelers legend Rocky Bleier serving teammate Joe Greene a Hungry-Man dinner fresh from the oven. Fellow athlete Washington Redskins' Charles Mann also appeared in commercials promoting the product line.

Microwaveable dinners are introduced

The microwave was invented in 1945 but didn't really enter the American home until the late 1960s. As it gained popularity in the 1970s, consumers were curious if Swanson's dinners could be cooked in one. The company had informed the public that they weren't. Since the dinners were made for ovens, the taste of the food could be compromised if cooked in a microwave. Also, the metal used for the tray could ruin the microwave itself. But Swanson took note of the growing trend. Campbell's Director of Marketing for Frozen Foods, William Culp II, told The Sacramento Bee in 1975: "Whenever microwave reconstitution maintains the quality of our frozen foods, special microwave instructions will be included on the package."

Four years later, Swanson introduced dinners tailor-made to be microwaved. Swanson's Vice President for Marketing and Development James R. Ernshoff likened the inevitability to what happened ironically in the television industry. Ernshoff told The New York Times in 1979: "As color programming grew — and, in particular, with NBC's decision to go to all‐color programming in 1964 — it exploded. We think the same takeoff will occur with the introduction of microwave‐compatible foods."

Swanson not only went all-in on microwaveable meals — including the introduction of a breakfast line called Great Starts – but it also acted as a resource for consumers. It established The Microwave Information Center, to give home cooks all the latest advice, tips, and tricks.

Swanson launches Le Menu, a low-calorie dinner line

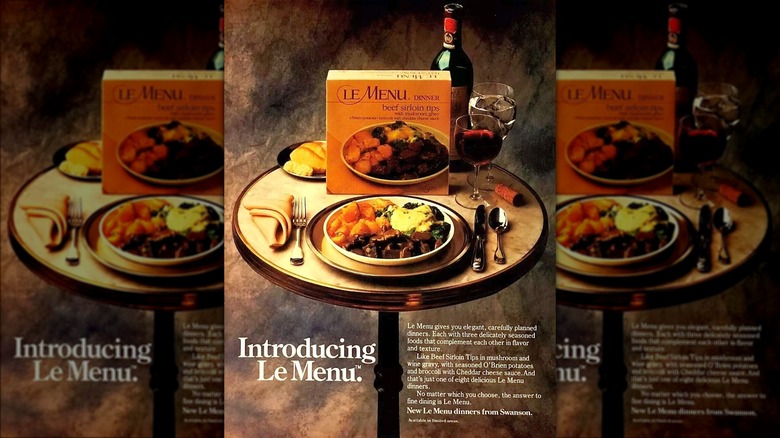

Despite the timely move to microwave-friendly dinners, Swanson's fortunes were still headed south. In the early 1980s, a larger emphasis was placed on healthier, more premium fare, including the frozen dinner market. Anne Neilson of research company Arthur D. Little Inc. told The New York Times that the original TV dinners were "sort of blue-collar, humdrum, practically tasteless. Now the manufacturers are aiming at a much more upscale market.”

Swanson spent a lot of money and effort on its Le Menu line, which made its debut in 1982. TV ads for Le Menu implored buyers to pair it with a vintage bottle of wine, seeking to elevate the frozen dinner dining experience to a whole new status of class. These less-fried, higher-priced, and lower-calorie dinners shared freezer space at the grocery store alongside the likes of Stouffer's Lean Cuisine and Weight Watcher's branded meals. By 1983, these dinners helped propel the frozen dinner industry to new heights, with $750 million in sales.

Trends shifted again in the following decade, and Campbell's turned its attention to Swanson's original core product: the frozen dinner. In 1994, as the brand was shifting its focus and advertising on the old school dinners, it bid adieu to its Le Menu offshoot. For American consumers who missed Le Menu, its Canadian neighbors to the north kept the line on shelves as late as 1998.

The company relaunches its product lines

In 1997, Campbell's saw Swanson, and its frozen foods, as one of its weaker assets. In order to focus more on its key products, it spun off the Swanson frozen foods division a year later into a separate company: Vlasic Foods International. Swanson CEO Robert Bernstock even said in a public meeting: "Swanson has missed every food innovation since the Korean War" (via Courier-Post).

Hoping to reverse the falling behind further, in 1999, Vlasic re-introduced America to Swanson and its frozen dinners. Murray S. Kessler, president of Swanson said: "What parent doesn't remember having a Swanson dinner growing up? And who doesn't recall eating the brownie dessert first?" He added: "We explored and tested these anecdotes in national research and consumers and parents told us they had fond memories of growing up and enjoying the dinners because they were a treat." Swanson ramped up its advertising and ran with a marketing blitz called "Make New Memories with Swanson."

By then, Swanson was selling 160 million dinners a year, but was firmly in fourth place as a brand in overall frozen food sales. So Vlasic used the 45th anniversary of C.A. Swanson and Sons as a good excuse to turn back the clock and bring back the long-dormant term "TV Dinner" to the box. This retro packaging included a wood-paneled frame, TV dials, and a historic timeline on the back. It also offered up sweepstakes info that customers could win a big-screen RCA TV.

Swanson tries to make its frozen dinners fashionable again

After only three years in existence, Vlasic Foods International filed for bankruptcy in 2001. The assets of the company, including Swanson, fell into the hands of the newly formed company Pinnacle Foods Corporation. Pinnacle tried to inject new life into Swanson, investing $10 million dollars to upgrade the line. Dinner trays incorporated familiar name brands like Tyson Chicken, and the boxes got a cool blue makeover.

The "TV dinner" returned to home viewers' screens for the first time in 15 years with a tray-chic new marketing campaign branded ”Food That's in Fashion." Not everyone bought into this notion, including Rutgers University professor Michael Aaron Rockland, who told The New York Times: ”TV dinners as sexy — it almost sounds ridiculous."

In 2003, Swanson's TV Dinner turned 50 years old, and its little brother Hungry-Man turned 30. Pinnacle kicked off a year of celebration for the former with a birthday cake. In the following years, the company continued to play into the nostalgia associated with the Swanson line, even proudly spelling out on the box that it was the "Original TV Dinner."

The brand slowly disappears, as do its TV dinners

By the early 2000s, Pinnacle Foods Group had become a home for many struggling brands. Swanson was on a roster that included the likes of Duncan Hines, Mrs. Butterworth's and Log Cabin syrups, Van de Kamp's and Mrs. Paul's frozen seafood, Lender's bagels, and Celeste frozen pizza. In 2009, it added frozen goods giant Birds Eye Foods to its portfolio. Around that time, Swanson's name started to quietly recede from the public eye, and American shelves. By 2010, the Swanson name was removed from Pinnacle's website, and two years later, it was no longer mentioned in the company's press releases.

The name Swanson isn't entirely gone from American grocery stores, as Campbell's still sells soups, broths, and stocks under that brand. However, all that remains of the Swanson family of frozen dinners in the United States is the Hungry-Man line, which remains a popular choice for consumers.

ConAgra acquired Pinnacle Foods in 2018, and today, it carries the torch of Swanson's once-iconic frozen food lineage. Still, if one really has a hankering for a Swanson turkey dinner, you may be able to get one in Canada, as ConAgra Brands Canada sells it, and many other meals like it.