How Boxed Cake Mixes Forever Changed Home Baking

While today boxed cake mixes are associated with convenience, they weren't initially invented for this reason. In fact, it took many years and a great deal of advertising to enable these mix-and-bake products to officially join the ranks of convenience cooking. Though there is a sort of egalitarian principle to cake mixes — which enable anyone who might not otherwise succeed to skip the complications and turn out a successful baked treat — the phenomenon of these easy-to-prepare desserts has only ever run parallel to home baking. Reaching their height in the mid-20th century, cake mixes turned cake making into something psychological, even philosophical, as it forced bakers to confront a bigger cultural question: why we bake cakes in the first place.

Today, with baking from scratch and baking from a mix equally practiced in households, baking is more accessible than ever, and yet has not lessened the importance or appreciation of such desserts for special occasions. Though we've surveyed readers on their favorite boxed cake mixes, such preferences go beyond preferred brands. The acceptance of cake mixes into daily life has shown, besides a universal human sweet tooth, that making cakes and sharing them has always been important to us.

Cake mixes followed the industrial trend of convenience cooking

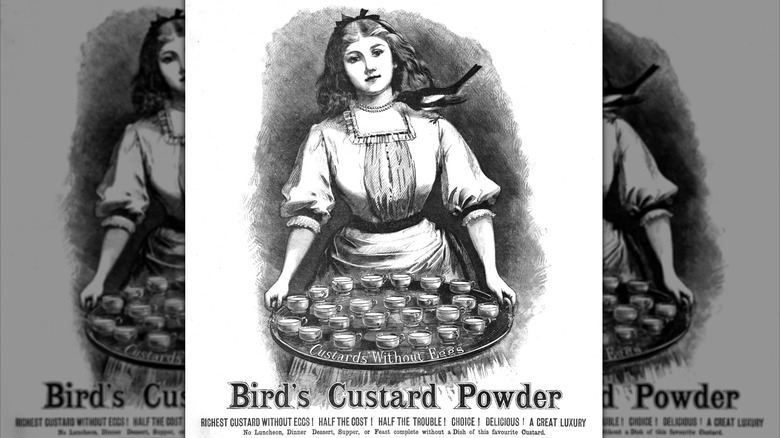

The mid-1800s was an era when chemistry was on the rise. Coupled with the industrial revolution of the period, this sparked a new concept of convenience in food preparation. Boxed cake mixes are the legacy of a long line of dry mix products that tested chemistry's limits. Custard powder was one such forebear of the dry mix revolution. Created by English chemist Alfred Bird, Bird's Custard Powder was invented in 1837, and the product eliminated the need for eggs in typical custard preparation. Another popular powdered product, gelatin, came to be in 1845 as the creation of American inventor Peter Cooper, which cut out the step of boiling animal hooves to obtain gelatin from scratch. This powdered gelatin went on to become the basis for Jell-O, a dessert that further tempted America's sweet tooth.

Despite the success of these individual powdered products, it took a bit longer for pre-made baking mixes to find their way onto grocery shelves, as the possibility for rapid leavening agents had to come first. With the helpful invention of baking powder, readily available as of the mid-19th century, the Pearl Milling Company introduced one of the first dry mixes in 1889, a pancake mix that was ready to cook with only the addition of water to make the batter. This pour and stir method of convenience set the stage for boxed cake mixes a few decades later.

Baking powder jumpstarted simplified baking

Even before cake mixes, there was another substance that permitted the simplification of cake-baking. Something we take for granted today, baking powder forever changed cake and pastry-making when it first became available in the mid-1800s. Prior to this innovation, cakes were a more difficult dessert, largely because of their need for a leavening agent, which made them a chemistry-intensive operation. Before baking powder, yeast was the go-to, but this had to be made from scratch — cultivated from fermented grains or produce. Once yeast was added, dough still had to be left to rise, which could take up to a whole day.

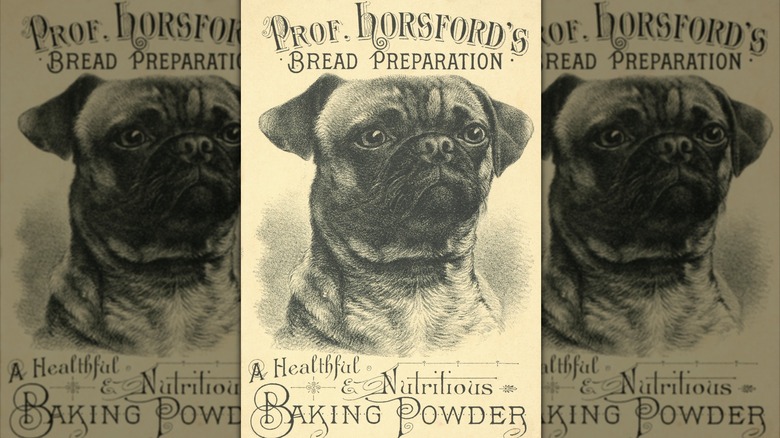

Though baking soda was invented first, in the 1840s, it only succeeded as a leavening agent when combined with something acidic, which led to many unreliable combinations. Alfred Bird, the same English chemist behind Bird's Custard Powder, successfully created a baking powder prototype with cream of tartar and baking soda. The result was reliable but expensive, restricting the powder to a luxury product. In 1856, American scientist Eben Norton Horsford concocted a different baking powder that was much less expensive to produce. He combined baking soda with monocalcium phosphate, which was first extracted from animal bones and later mined from the earth. Succeeding in combining monocalcium phosphate and baking soda into one container, Horsford's baking powder, which was later renamed Rumford's, revolutionized home baking, turning cakes into something that took only an hour or two, rather than an entire day, to prepare.

Sliced bread led to a market for new flour uses

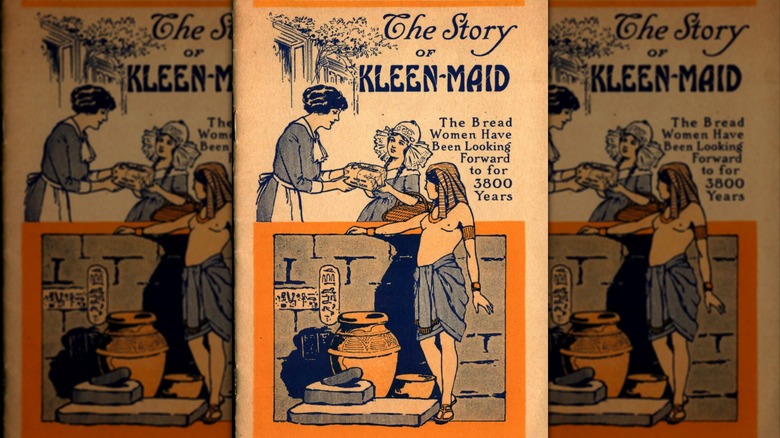

As innovations for home baking progressed throughout the 19th century, so too did innovations in commercially produced baked goods. This slow-burning revolution was changing everyday culinary practices, and the shift was especially noticeable in American households. Before the 20th century, women almost exclusively baked bread from scratch. But this became a less and less common practice as commercially produced breads became affordable, saving countless hours in the kitchen. Homemade bread was starting to become an antiquated practice by the 1920s, made even more obsolete by the invention of sliced bread in 1928, which completely rerouted America onto the path towards convenience that other countries would later follow.

With no need to have 100-pound sacks of flour on hand as was the way in the previous century, American pantries had much less need for this former household necessity. Flour companies, as a result, were struggling to keep selling to American households. As a result, brands required some creative thinking (and convincing advertising) in order to rebrand and reimagine flour as a pantry staple for something other than bread. This paved the way for cake mixes in the following decades, though ironically it was not a flour company that first had the idea.

A molasses company pioneered cake mixes

It was a molasses company that dreamed up the idea of dry cake mixes. Pittsburgh-based P. Duff & Sons was originally looking for a way to use up a surplus of their primary product. So, the company came up with the idea of dehydrating molasses and mixing it in with the other necessary ingredients to produce a baking mix that only required water to be ready to bake. Duff's Ginger Bread Mix, first introduced in 1931 and sold in tin cans, may not have originally been for a literal cake, but the brand evolved quickly to turn "Ginger Bread" into something cake-like.

Introduced to the public during the Depression, however, the hypothetical convenience of Duff's product did not quite hit home. Duff's mixes sold, but not incredibly well, perhaps because they came out at a time when families were more focused on necessity than convenience. Another problem with completely dehydrated mixes that would pose much debate in the following decades was something Duff noted in a 1933 patent application for his mix, emphasizing that "dried or powdered eggs... while entirely satisfactory in many ways, are considered by some as inferior material."

Regardless, Duff's was ahead of a trend. Following cautiously, General Mills had a bit more success with its invention, Bisquick, released the same year as Duff's mix. Though not specifically for cakes, Bisquick was a precursor to the conveniences to come. Otherwise, flour companies took a while to make mixes of their own.

During WWII cakes were more about making do

Though flour companies eventually caught on to the idea of ready-made baking mixes, their first clientele was not the general populace. Catching on just as war was breaking out, dry mixes were initially adapted for the convenience of troops overseas during WWII. Meanwhile, women on the home front were still baking cakes, but these desserts were adapted to the new shortage of traditional ingredients that came with wartime rationing.

Still opting to make cakes from scratch, home cooks preparing wartime cake recipes came up with creative solutions that made the most of chemistry in times of ingredient scarcity. Wacky cake was one such wartime dessert, a typically chocolate cake that required no eggs, butter, or milk — oil sufficed for fat, and a reaction between vinegar and baking soda created a leavening effect. Mayonnaise cake was another popular dessert that can be traced to before the Depression, but really got the limelight in the 1940s with wartime shortages prompting alternative baking ideas. These culinary innovations were more the norm during wartime than any ready-made mixes that had been trying to find their place on the market. Consequently, convenience had less clout and may have seemed unnecessarily luxurious during another moment in history when resources were more scarce than usual.

Cake mixes' golden era was the postwar boom

Cake mixes finally found a place in daily life after WWII, when women who had started taking on jobs to help the war effort also starting running households, finding themselves busier than ever. With very little time leftover, homemakers sought time-saving cooking hacks, which finally created a demand for the convenience foods that had slowly been gaining ground throughout the 20th century. Cake mixes were just one of many easily-prepared items that gained popularity after the war, and there was enough of a demand for them that a slew of new companies popped up in the 1940s. By 1947, there were more than 200 cake mix brands.

Though the war had devised new food dehydrating technologies that were formerly employed to feed troops, cake mixes didn't necessarily improve with these innovations, and for most consumers, remained second to homemade. Despite a mix's promise of convenience, consumers were not entirely converted when it came to cake mixes, largely because the mixes themselves needed a bit of reworking. Many claimed they were less palatable, with odd flavors coming from the dehydrated ingredients that went into a dry mix. In some cases, the consistency was the problem, which led to some unusual solutions, including the addition of soap into some cake mixes as a means of improving texture.

Big brands made mixes mainstream

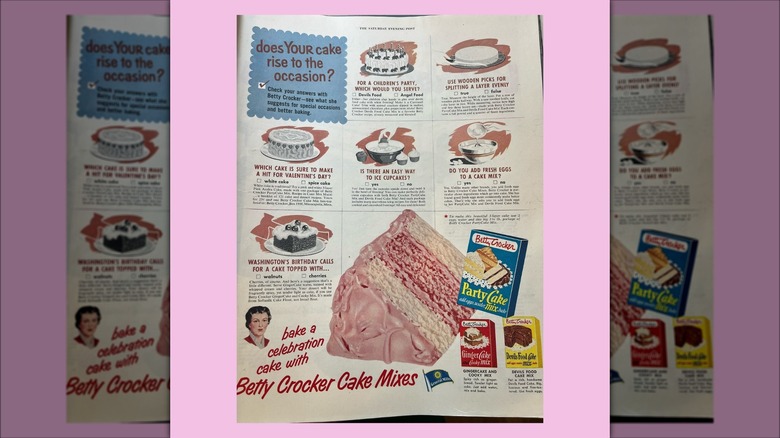

While cake mixes had certainly earned a place on grocery and pantry shelves by the mid-1940s, the entrance of opportunity-riding big brands changed the cake mix industry. General Mills officially joined the game in 1947 with its Betty Crocker Gingercake, eventually expanding to create batter and frosting combinations with up to 64 possibilities. Pillsbury followed in 1948 as the first brand to introduce a chocolate cake mix, and Duncan Hines came in 1951. With time, more and more flavors stormed the market, though brands have since discontinued many of these cake mixes.

By the 1950s, consumers were certainly buying mixes, but it wasn't as many as brands hoped for, and furthermore not the demographic they were targeting. Busy farmwives made up the vast majority of the cake mix customer base, as their bustling lives and pressure to feed large groups of workers welcomed the convenience of a ready-to-bake dessert. The suburban and city-based young wives, budding bakers, and homemakers simultaneously balancing jobs, however, seemed to still prefer making cakes from scratch. There was still a sense of prestige that came from homemade baking, and, as culinary historian Laura Shapiro writes in her book "Something in the Oven," "the prospect of serving a cake that took no skill just wasn't very alluring. Good cooks were proud of their handiwork." This sentiment puzzled the companies trying to market cake mixes. Consumers were proving that time and quality still seemed to hold value over convenience.

The 'to add or not to add eggs' debate

In order to convert more home bakers over to cake mixes, brands experimented with the psychology of cake baking, and how involved a baker had to be in order to feel like they had truly made a cake themselves. As previously mentioned, John Duff of Duff's molasses knew early on that the convenience of an entirely dehydrated baking mix was not necessarily what home bakers were looking for. "The housewife and the purchasing public in general seem to prefer fresh eggs," Duff asserted back in 1933, elaborating, "hence the use of dried or powdered eggs is somewhat of a handicap from a psychological standpoint."

Two decades later, psychologist Ernest Dichter, while carrying out a study for General Mills, came to the same conclusion after he interviewed women about their feelings surrounding cake and the joys and trials of baking it. Dichter's study, though not the first to conclude that women preferred fresh eggs in their cake mixes, started the movement in the 1950s towards cake mixes adapted to a more involved baking experience. Many consumers found the dried eggs in just-add-water mixes unsavory anyway, as they could have an overpowering flavor. General Mills' Betty Crocker cake mixes made this a selling point in the advertising of the period, noting that there were no powdered eggs in the brand's dry mixes. Betty Crocker touted its cake mixes' subsequent superiority because they brought a "special homemade goodness" since "you add the eggs yourself."

Regional innovations kept cake mixes on shelves

Cake mixes kept evolving as they became fixtures in everyday life. It had become apparent by 1949 that mixes sold in America didn't universally work across a country with such diverse terrain. In places of high elevation, specifically, cake mixes fell flat because the pre-packaged ingredients were not adapted for lower air pressure. Helena, Montana's, Independent Record reported of Pillsbury's efforts to adapt mixes regionally: "A recipe providing a perfect light cake in Herkimer might result in something as flat as a cold omelet in high altitude Denver." The New York Times elaborated on this point: "Directions on the packages for areas with an altitude up to 3,000 feet call for more liquid than those sold in sea-level cities." The NYT adds that Pillsbury, thanks to its elevation adaptations, "gives to the distributors and the grocers the responsibility for seeing that a housewife gets the kind of mix designed for 'baking at the altitude at which she lives.'"

Another regional adaption to cake mix baking was the innovation of the Southern soda cake, sometime in the 1950s. Turning baking into a "two-ingredient" process, soda combined with cake mix transformed cake baking back into the ultimate convenience and eliminated the egg question. Soda's carbonation meant no need for eggs or additional liquid in cake mix batter, as it proved to be an effective leavening agent. This unassuming chemistry phenomenon, however, has remained largely associated with the Southern United States.

Icing possibilities created a new cake mix trend

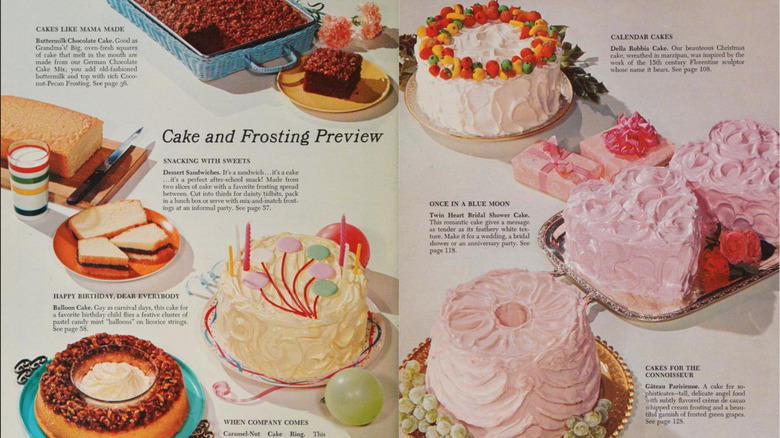

Even more of a widespread success than the psychological branding practice of adding fresh eggs back into the equation was the progression of a different aspect of cake baking: the icing on top. Trying to keep demand fresh, cake mix companies pivoted next towards heavy advertising for cake decoration, to convince consumers that the decorative aspect was a cake's personal touch, rather than the cake itself. Consequently, mid-century ideas for cake decorating became increasingly more extravagant — icing also helped to mask any artificial flavoring that still had a tendency to define cake mixes.

"There was this faux creativity to make up for the fact that you're not actually baking a cake," Laura Shapiro explained her research findings to Bon Appétit. "This decorating obsession sold the idea that, this way, you're making this cake yours."

With or without enhanced decoration, cake mixes were still winning over unlikely converts little by little. Poppy Cannon, food editor and cookbook author, was such a believer in cake mixes that she brought a suitcase full of them to Paris in the 1950s for her friend Alice B. Toklas, lifelong partner to the writer and art collector Gertrude Stein. Shapiro records Toklas's reaction in another article for Gourmet Magazine: "About the mixes, I've had huge success with the yellow cake. It is perfect. The devil's food cake was equally successful... Delicious!"

Mixes have changed the meaning of homemade

Though cake mixes may no longer be in their golden age, they have found a permanent place on grocery and pantry shelves. Ironically, cake mixes themselves are largely responsible for the introduction of the phrase "from scratch" in the modern culinary lexicon. Though the origins of this phrase are a bit hazy, it has been employed as a common kitchen term since the 1940s, originally used as a means of distinguishing cake mix cakes from those made, well, from scratch. While cake mixes may originally have been compared to cakes made from scratch, mixes have since become so widely used that they have turned the scratch definition on its head — for many home bakers today, baking "from scratch" means whipping up a cake from a boxed mix.

"One of the most dramatic things that ever happened to me was, as a reporter in the '90s, finding out that in a survey women always say they bake from scratch — but they meant they used a mix," Laura Shapiro explained further for Bon Appetit. "Cake mixes redefined what 'baking' meant." Today it's true that our cultural perspective of cakes has changed, but that may only be because commercialization and kitchen conveniences have continued to advance. After all, cake made from a mix still technically counts as "homemade," and is an ideal middle ground between ready-to-eat store bought cakes and true from scratch baking.