Why Wolfgang Puck Says Your Palate Is The Key To Better Cooking

There's no denying chef Wolfgang Puck's reputation in the culinary world. He's won James Beard Awards, garnered Michelin stars, been inducted into the Culinary Hall of Fame, and, thanks to his TV work, you'll even find his name in a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. All of this (apart from the Walk of Fame star, perhaps) makes him more than qualified to throw his hat into the ring regarding how to become a better cook.

Puck recommends working on developing your palate to improve your cooking. To the uninitiated, the palate may seem like quite a lofty concept. The Cambridge Dictionary defines it as, "A person's ability to taste and judge good food and drink." And while the temptation is to assume this is an innate quality, like having a high IQ, this is far from the case.

It's certainly true that we are not born with identical palates. Some people have greater sensitivity to certain tastes, and it's even been suggested that women may be better tasters than men. However, everyone can train their palate and, conversely, harm their palate through choices like smoking. But how exactly does one train the palate? And why will this improve your cooking? As it turns out, there's more than one answer to each question.

Why training your palate will improve your cooking

The professional study of cooking is called Culinary Arts for a reason. The palate is important to a cook because cooking is fundamentally a creative medium. On the MasterClass website, Wolfgang Puck elaborates: "Musicians have to train their ears to listen to music; painters have to train their eyes to learn about perspective and how to mix colors. We, in the kitchen, have to learn how to train our palate and how to season things properly because without that, you can buy the most expensive ingredients, and the food will taste flat."

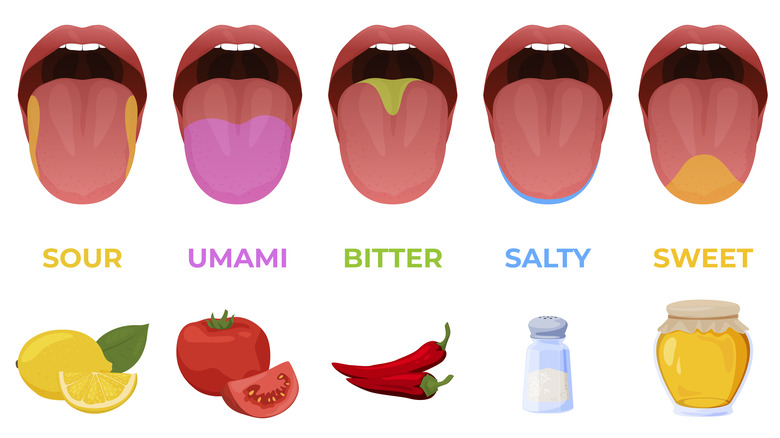

There are five basic tastes: Sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami, which are found in ingredients everywhere on earth. For example, umami (sometimes called savory) can be found in parmesan, mushrooms, green tea, sundried tomatoes, soy sauce, and other diverse foods. One way Puck advises to train your palate is to try new foods. This allows you to gain experience identifying the balance of the five tastes in what you eat.

In the U.S., many people don't find chicken feet appealing, but they're a much-loved delicacy elsewhere in the world. On the other hand, dairy foods are firmly ingrained in Western society but are not often consumed in many Asian countries. Your passion for cheese — or chicken feet — is decided by what foods you have been exposed to. You'll only learn to harness an ingredient's unique culinary potential (and to love it) by trying it first.

How to train your palate

No one becomes a master of cooking simply by eating. Where your palate training will level up is while you're cooking. One way is to use better quality ingredients, which offer more complexity, flavor, and intensity than cheaper versions, making it easier to learn from their more discernable taste in your cooking. A quality olive oil, for example, can elevate dishes enormously.

It's also good to accentuate flavors where possible. Wolfgang Puck has previously shared advice on the spices you're best off toasting, but almost all spices will give off more flavor when lightly toasted. Toasting works well for reviving stale spices, too. However, Puck also cautions not to overdo it with the seasoning. You can always add more salt, but removing it from a dish is tricky — although some dishes, such as soup, can be saved. Puck suggests adding a source of fat to an oversalted soup. Alternatively, you can fix overly salty soups by adding potatoes.

Puck has one more seasoning tip: Cold foods require more seasoning than hot foods. This is because heat disperses flavors on the palate more rapidly, and also because when spices are heated they release essential oils and aroma, causing their flavors to intensify. The final — and most important — way to train your palette is to taste everything as you're cooking. The more you taste, the more practice you'll have using your palate to decide how to improve or correct a dish.