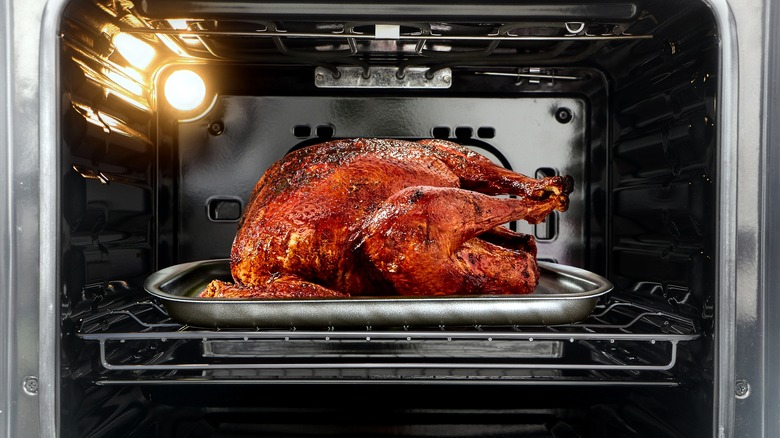

The Dry-Brining Timing Tip To Follow For The Juiciest, Most Flavorful Turkey

There's a little-known secret about roasting a turkey: You can actually do it any time of year. That said, brining and roasting a turkey takes a lot more time than a chicken, and feeds a lot more people, so most people reserve their turkey-roasting projects for big holidays like Thanksgiving. How much time is a lot? Depends on the size of the bird and the type of brine.

Our recommendation is dry-brining, which has the benefit of being less messy, generally speaking, than wet-brining; it doesn't require a big bag or bucket of raw turkey tea, but results in turkey just as juicy and flavorful — and with crispier skin. The general rule is to dry-brine your turkey uncovered, in the refrigerator, for an hour for each pound of the turkey's weight.

The salt rub in a dry brine draws moisture out of the turkey's protein cells through the process of osmosis. Those extracted juices dissolve some of the seasoning of your rub. Then, to reattain equilibrium, the cells pull that now flavored moisture back into the meat. It's a fascinating process that takes time; it's no small feat to pull out the natural moisture in the turkey and replace it with brine, but it yields meat that's flavored from the inside out. If you have a 10-pound bird, you'll need to let it sit for 10 hours. If you have a 20-pound bird, it'll take 20 hours to brine in the fridge.

Why is the timing important?

As anyone who has ever made one knows, turkeys are big birds, which is why brining them is a long, somewhat delicate process. As the salt penetrates the turkey's tissue through the osmotic exchange we described, the brining process happens bit by bit — it's not as if the grains of salt on the skin yell out to the moisture in the deepest cells of the turkey breast to march forward. The surface is affected first; then, the salt enters the tissue and reaches the next layer, and the process continues. If you cut off the brining process too soon, it won't complete, and there could be a noticeable difference in thicker pieces of meat. Depending on how short you cut it, it might not have enough time to properly dehydrate the skin and it won't be as browned and crispy as it could be.

The good news is that while underbrining is a concern, you almost can't overdo it; Alton Brown notably dry brines his turkeys for four days. From one to four days, the only concern is going to be running out of fridge space. Eventually, the turkey will begin to cure — but that could take weeks or months. You probably won't wait that long to roast your turkey anyway.

Why should turkey be uncovered during dry-brining?

While juicy meat is a key part of any well-roasted turkey, the other thing that creates flavor in your turkey is a deliciously browned, crispy skin, thanks to the Maillard reaction. This is the same effect responsible for the crusty exteriors of baguettes, the sear on a steak, and the browning of browned butter. It's a thermochemical reaction; the amino acids in the turkey and the sugars in your dry brine react under heat to produce all that browned goodness.

The delicious Maillard reaction can only happen above 285 degrees so if your turkey's skin is wet, you're going to have a problem achieving it. Water's boiling point is 212 degrees Fahrenheit so any water on your turkey's skin has to boil off before the skin will start to brown — and that will take time (and risk drying out your bird) unless you dry out the skin before the turkey goes into the oven. This is where storing it uncovered in the refrigerator comes in.

By letting your exposed turkey skin dehydrate in the dry environment of the fridge, you're jump-starting the process for a successful Maillard reaction — a critical step in not drying out the turkey while you try to get the skin to crisp and brown. You worked hard (or, at least, waited a long time) for the juiciest, most flavorful turkey; don't let it all fall apart in the oven.