The Ultimate Guide To Japanese Wagashi Confectionery

Wagashi, or Japanese sweets, have a rich history in Japan and are often eaten with green tea during tea ceremonies or offered at temples. But how much do you really know about this traditional Japanese confectionery?

There are many different types of wagashi — over 60, in fact — as well as different categories. Wagashi are often intricately crafted by hand, and they're also seasonal, with different types of confectionery eaten depending on the time of year or at specific celebrations.

Our guide to wagashi will dive into the origins and history of this confectionery. We'll explain all you need to know about the types of wagashi, when they're eaten, and how best to enjoy them.

We'll also look at where you can buy and enjoy wagashi in Japan, the U.S., and worldwide. There's so much to learn about this popular Japanese teatime treat, so without further ado, let's dive deep into our ultimate guide to wagashi.

What are wagashi?

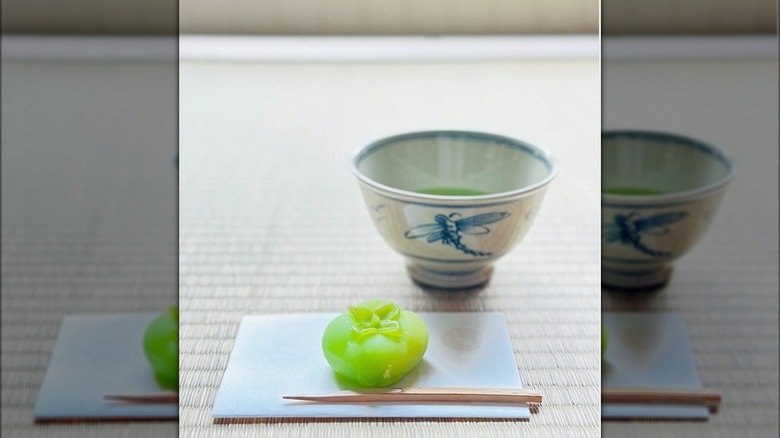

We already mentioned that wagashi are traditional Japanese sweets often eaten at teatime in Japan. Wagashi are traditionally formed by hand and resemble edible art, making them a popular gift or treat to serve visitors to your home.

The shapes and colors of wagashi change with the seasons. In Japan, shape, color, texture, and taste all hold equal importance when it comes to wagashi.

Wagashi is an important part of the Japanese tea ceremony. The confectionery is served before Matcha, to complement the green tea's bitter flavor.

Early Japanese confectionery came from China and dates back to 538-710 (the Asuka period). Some say that the deep-fried treat Kara-kudamono is the predecessor to wagashi. This type of confectionery was only for the rich, as sugar was a rare and expensive luxury.

It wasn't until the Edo period that wagashi's popularity boomed in Japan. As sugarcane became more widely available and affordable, special stores selling wagashi opened in Edo (modern-day Tokyo) and Kyoto, and wagashi's place as an important part of the tea ceremony was cemented.

There are three categories of wagashi

Wagashi fall into three categories: Namagashi, which are fresh sweets, higashi, the dried confectionery, and han namagashi, or half-dry sweets. However, there are many different types and variations of wagashi within these three categories.

Not only are there a huge range of different types of wagashi, but they also change with the seasons. For example, some wagashi, like wanama, is colored pink for cherry blossom season in the spring.

Other wagashi vary depending on the seasons, too, such as ohagi/botamochi. Namagashi such as yokan is most commonly found in the summer months, when it can be chilled for a refreshing treat.

Fresh wagashi has a much shorter shelf life than dried or half-dry varieties. For this reason, it can be harder to source namagashi outside of Japan, unless you have a specialist wagashi store in your city. We'll look more at where to buy wagashi in a moment.

Wagashi change with the seasons

We already touched on the fact that wagashi vary with the seasons, but why is that, and which wagashi can you find in specific seasons? Let's take a deeper look.

The colors, intricate shapes and designs, textures, and flavors of wagashi show an appreciation for the changing seasons. In spring, cherry blossom season arrives in Japan, so you may see pink and purple plum and cherry blossom wagashi. As summer approaches, green wagashi are common, often representing bamboo leaves.

As we move into fall, deep oranges and browns for foliage, as well as moon-shaped or themed wagashi make an appearance, with flavors such as chestnut and persimmon. This is the time for Japan's Otsukimi Festival when the Harvest Moon is visible, similar to the Mid-Autumn Festival celebrated in other parts of Asia.

Winter brings the snow, and many wagashi found in winter are shaped like snowflakes. They also often contain health-boosting ingredients such as yuzu, a Japanese citrus fruit, black beans, or strawberries.

Where to buy and enjoy wagashi

If you're lucky enough to live in Japan or are planning a trip there, you'll find plenty of places to enjoy wagashi. Wagashi is generally served anywhere you find green tea, so you can enjoy it at temples, in gardens, or in restaurants or cafes across Japan.

If you want to buy wagashi to enjoy at home, you also have a number of options. Kyoto, Tokyo, and other Japanese cities have street food vendors preparing and selling beautiful wagashi. If you're in Tokyo, head for Asakusa district and check out the wagashi available on Nakamise, a shopping street packed with vendors selling traditional snacks.

You can also buy wagashi in most supermarkets and Konbini (convenience stores) in Japan, as well as some larger department stores. In addition, larger cities have specialty wagashi shops where you can pick up sweet treats, such as Tsuruya Yoshinobu, which has branches in Kyoto and Tokyo.

If you're outside Japan, in the U.S., Europe, or anywhere else, you may be lucky enough to have a specialist wagashi store in your city. In major cities such as New York, you'll be spoiled for choice. If you're in Paris, be sure to check out Toraya, a renowned Japanese sweet shop.

Outside of major cities, you're unlikely to find fresh wagashi anywhere, though if you're near an Asian grocery store you may find seasonal dry and semi-dry wagashi. You could even order wagashi online, with a number of subscription boxes available.

Different types of wagashi

Before we dive into the different types of wagashi in detail, let's take a quick look at some of the many varieties available. You'll find wagashi that are more like cakes or pancakes alongside tiny, dainty teatime candies and refreshing jelly wagashi.

Dorayaki, monaka, and manju are three popular types of wagashi we'll explain more about shortly. While dorayaki is made from two small pancakes, monaka includes two sweet rice wafers, and manju resembles a steamed bun. These types of wagashi are usually sandwiched or filled with a sweet paste, which can vary depending on the season.

Jellied wagashi, such as yokan, is most popular in the warmer months. Mochi wagashi, like Daifuku, also varies with the seasons, with strawberries popular in the wintertime. Wagashi doesn't have to be sweet either — you'll find dango available in both sweet and savory flavors.

Wanama

Although wanama comes in a wide variety of shapes and colors, it is at its prettiest during cherry blossom season in spring, when much of the wanama on sale is pink. Wanama is a type of namagashi or fresh wagashi. If you're buying it at a store, it's best enjoyed within a couple of days of purchasing or it may turn hard.

Most wanama is made with shiratamako (sticky rice flour) with sugar and white beans. It's a soft confectionery that's the perfect complement to matcha due to its sugar content.

Traditionally, wanama is eaten by cutting it into small slices, one at a time, and popping them in your mouth using the included utensil. At a tea ceremony, guests will be provided with a Youji or Kuromoji designed to make it easy to slice the confectionery. These tiny knives are made of stainless steel and wood, respectively.

Dorayaki

Dorayaki takes its name from the Japanese words "Dora" which is a type of gong, and "yaki" meaning "cooked over a dry heat." This is one of the types of wagashi you can find prepackaged in Asian supermarkets or convenience stores, though if you can find a vendor selling fresh dorayaki, it will be at its most delicious.

Dorayaki looks like a type of cake, usually consisting of two small round pancakes or one bigger one folded in half. The pancakes are typically sandwiched with red bean paste known as anko, but other fillings like sweet chestnut paste, matcha paste, or custard can also be found, depending on the time of year.

In the past, Dorayaki didn't look like it does today — in fact, this version only arrived in the 20th century. In Japan's Edo Period from 1603 to 1867, Dorayaki had just one layer that was folded in half, like an omelet.

Monaka

Monaka is a type of wagashi that resembles a biscuit. You'll find it comes in a variety of shapes and colors depending on the season, from cats to cherry blossom flowers.

Whatever its shape or color, monaka consists of two rice wafers sandwiched with filling. Though the wafers are made from mochiko flour, monaka is not a type of mochi. It can be filled with sweet bean jam, fruit, or chestnut paste. Some monaka are filled with ice cream or mochi.

This is another sweet that first appeared during Japan's Edo period. The name monaka is thought to come from a poem by Minamoto no Shitago. Originally, they were called "monaka no tsuki," meaning moon in the middle, after court nobles who read the poem saw these types of sweets served at a banquet held to view the moon.

Later, the sweets became available in other shapes. Following this, the name was shortened to monaka.

Yokan

Yokan is one of the most popular jellied wagashi. This red or white bean jelly is made with kanten, a substance that's similar to gelatin and made from seaweed.

This confectionery originated in the Kamakura-Muromachi period between 1185 and 1573. Originally, it was made with gelatin from boiled mutton, but since Buddhist monks were vegetarians, they created a version they could eat, made with azuki beans and kanten.

Yokan is often colorful and looks beautiful next to a bright green cup of matcha. Though it's commonly made with azuki beans, variations can include chestnut, sakura, matcha, or a whole host of other ingredients.

You'll usually find yokan is sold in blocks, and is most popular during the month of July. To serve, it's cut into slices.

There are actually three different types of yokan to choose from. Neri Yokan is the most popular type, mizu yokan is made with more water for a plumper, jelly-like texture, and mushi yokan is steamed, giving it a delightful chewiness.

Daifuku

Daifuku is another type of wagashi that you'll find in Japanese or Asian grocery stores. It's usually made with a mochi ball filled with fruit or sweet red bean paste, though other fillings are available too.

This sweet treat dates back to the Edo period, when the process of making mochi was first invented. It was originally larger and called harabuto mochi, meaning "fat belly mochi" for its round shape and generous filling.

Later, the name was changed to daifuku, meaning "great luck" in Japanese. Daifuku are commonly eaten during Japanese New Year celebrations, and are said to bring good fortune and good luck. They're also popular at spring festivals and other celebrations throughout the year.

You'll find different varieties of daifuku depending on the season. In the winter months, ichigo daifuku filled or topped with strawberry is popular during Japanese strawberry season, which runs from winter to spring. In spring, pink sakura daifuku with sakura blossoms celebrates cherry blossom season.

Ohagi/Botamochi

Ohagi or botamochi are often a deep red color, which comes from the coating of red bean paste, though they can also be green, brown, or a variety of other colors depending on their ingredients. These sweet rice balls are usually round or cylinder-shaped.

Some ohagi or botamochi are filled with red bean paste. Despite the difference in name, ohagi and botamochi are the same thing. In spring, they're called botamochi, after the springtime flower, botan. In fall, they're known as ohagi, after the fall flower, hagi.

Whatever you call them, these wagashi are served during the Buddhist holiday Ohigan, which lands during spring and fall equinoxes. This holiday is a time to honor ancestors, when the veil between the worlds of the dead and living is said to be at its thinnest.

Ohagi and botamochi are also eaten during another Buddhist holiday, Oban. Once again, this is a time for Japanese people to honor their ancestors and visit the graves of departed family members. Ohagi and botamochi are often offered at gravesites, with the azuki beans said to ward off evil.

Rakugan

Rakugan is a type of dry wagashi that resembles a hard candy. It comes in a variety of intricate shapes and is also known as uchimono or uchigashi. It's made with mijinko (glutinous rice flour), sugar, mizuame (a Japanese sweetener), and cereal flour.

Despite rakugan's popularity as a Japanese sweet, it's actually thought to have originated in China. It's said to be related to a sweet known as nanrakukan, which was made with mizuame, sugar, and glutinous rice flour and shaped in a mold.

This sweet treat made its way to Japan during the Ming dynasty and could later have been called rakukan before evolving into rakugan. Though it was originally served at tea ceremonies, white rakugan, in particular, became a popular offering to the gods and ancestors.

The texture of rakugan is similar to cookies, and its sweetness makes it the perfect complement for bitter tea such as matcha. Sometimes, rakugan is even added to hot drinks to impart sweetness.

Dango

You'll find dango in almost every Japanese city, commonly served on skewers at street food stalls. These little glutinous rice flour balls are boiled or steamed, and they're a bit chewier than mochi.

Dango are thought to have their roots in India, where they supposedly originated from the Indian dumpling modak, often used in offerings to deities. Today, you'll find many different types and regional variations of dango available.

Popular sweet varieties of dango include cha dango, flavored with green tea and hanami dango, tri-colored balls of dango that are available during Japan's cherry blossom season. Dango doesn't have to be sweet either, with shoyu dango, flavored with soy sauce, a popular snack in Japan.

Other popular regional dango varieties include zunda dango, made with sweetened edamame, kurumi dango, with walnuts, jury dango, made with chestnuts, and ayame dango, with Iris flowers. In the Kanto region of Japan, white sukimi dango are enjoyed as an important part of moon-viewing celebrations.

Manju

Manju look a bit different from other types of wagashi. They most closely resemble fluffy steamed buns or cakes, and are usually baked or steamed, filled with sweet bean paste.

You'll find manju available in various different sizes and shapes. Their subtle sweetness means they're delicious with green tea.

Like many other Japanese sweet treats, manju were originally brought to Japan from China. They arrived with a Japanese envoy in 1341, and were originally called mantou.

The red bean paste or anko used to fill manju comes in three different types: Koshian, a fine paste, Tsubian, a chunky paste, and Tsubushian, a semi-chunky paste, depending on your preferences. Manju also have a variety of different fillings, depending on the region they're from.

Fillings include shiro-an, white bean paste, miso bean paste, sesame paste, chestnut paste, and matcha paste. Where wheat flour is generally used for most manju, other varieties, such as Jyouyo Manju, are made with rice flour.