Bacon: Here's How It's Made

Bacon's journey is as rich as its flavor, originating from ancient China and traveling through various cultures, evolving in its preparation and significance. Its traditional production techniques, like dry-curing, laid the groundwork for what many savor today. The curing process, essential for preservation, uses ingredients like salt and nitrates, giving bacon its distinctive taste. Over time, as demand surged, more industrialized methods emerged, raising concerns about sustainability and animal welfare. Alternatives to traditional pork bacon, like Schmacon, turkey bacon, and even plant-based options, have since entered the market, reflecting changing consumer preferences and dietary needs.

Beyond just being a breakfast staple, bacon has embedded itself into modern culture in unexpected ways — you can make a lot of things with bacon. It has become an ingredient in cocktails, inspiring innovative pairings, notably with bourbon. Its flavor profile has also transcended traditional meat, leading to creations like bacon-flavored gums, popcorn, and even ice creams. This culinary chameleon has managed to remain relevant, adapting and innovating, while always reminding us of its deep-rooted history.

A rich history

The etymology of "bacon" is rooted in ancient linguistic traditions. Originating from the Old High German term 'bacho,' it alluded to the rear part or the "back" of an animal. This gradually evolved in the Proto-Germanic language to become 'backoz.' Centuries later, around the 14th century, French linguistics adopted the term as 'bacun,' designating the meat from a pig's back. Fast forward to the 16th century, and the English language introduced 'bacoun' to describe not just specific cuts, but all forms of preserved pork.

Ancient China saw pioneering strides in meat preservation, exemplified by the development of "La Rou", a type of salt-cured pork crucial for ensuring uninterrupted food supplies throughout the year. An article from 2012, titled "History and heritage of Jinhua ham" in the Animal Frontiers section of Oxford Academic, brings to light a tale from Zhejiang province. The narrative suggests that the method of salting meat could have been serendipitously discovered when locals unearthed pigs preserved in a mixture of sea salt and sand after being flooded by seawater. The Tang Dynasty (A.D. 618–907) is pinpointed by the article as providing the earliest recorded instances of this preservation technique. By this juncture, ham processing had proliferated across China, with the Jinhua region particularly acclaimed for its high-grade hams.

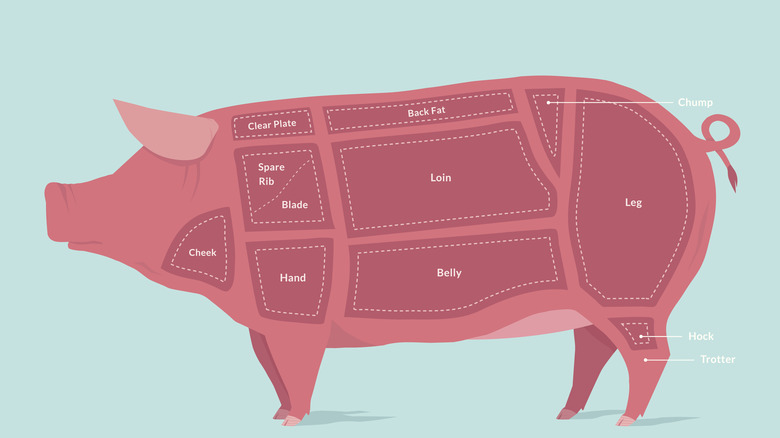

Bacon anatomy

Bacon's variety hinges largely on the specific cut of the pig. The United States Department of Agriculture defines bacon as a cured meat sourced from the belly of a 6-month-old swine carcass. This definition gives rise to the familiar streaky bacon, characterized by its alternating bands of pink meat and white fat.

In the U.K., the favored bacon cut is back bacon, which is sourced from the loin located in the middle of the pig's back. This cut is characterized by its leaner and meatier texture compared to the typical fatty belly bacon. In the U.S., a similar cut is referred to as "Canadian bacon." Yet, in Canada itself, traditional "Canadian bacon" is known as peameal bacon. This variant undergoes a sweet pickle cure and is coated with yellow cornmeal. Historically, this bacon earned its "peameal" name because it was originally coated with ground yellow peas to enhance preservation.

Beyond these popular types, we also have jowl bacon, made from pork cheeks, offering a rich, fatty profile, and prized for its tenderness. In contrast, Arkansas Bacon is derived from the pork shoulder blade Boston roast, which after certain bones and excess fat are removed, is dry cured using natural ingredients like salt, sugar, and spices, then smoked.

Traditional production

In traditional meat preservation, curing has always played a pivotal role, with its origins dating back to times when refrigeration was nonexistent. The primary agent in this process, salt, is indispensable, drawing out moisture from the meat and creating an unfavorable environment for bacteria. Moreover, when used in tandem with other seasonings and agents, salt contributed significantly to the meat's characteristic flavor.

Dry curing, especially, has stood out as an artisanal favorite. This process involves rubbing the meat with a mixture of salt, sometimes sugar, seasonings, and key curing agents, typically nitrates or nitrites. These compounds, while acting as preservatives, also impart a distinct pink hue to the bacon, setting it apart from its uncured counterparts. Once applied, the meat is refrigerated and allowed to cure, ranging from a week to several months, depending on the meat's dimensions. After this curing stage, the bacon still needs to be cooked before consumption.

This traditional technique is not exclusive to bacon. Many other revered charcuterie items, such as prosciutto, salami, and specific hams, owe their unique textures and flavors to dry curing. The blend of ingredients and curing time directly influence the final taste of these meats, as detailed in a 2014 study from Animal Biosience.

Smoking

Following the traditional dry curing process, smoking typically becomes the subsequent step, further enriching bacon's flavor profile. While smoking imparts a distinct smoky taste, the chosen technique can significantly shape the final product. Cold smoking exposes bacon to a low-temperature smoke range of 55 to 85 degrees Fahrenheit, endowing the meat with a smoky aroma without actually cooking it. It's essential to understand that bacon cold-smoked should be thoroughly cooked before being consumed. The USDA cautions that temperatures spanning from 40 to 140 degrees Fahrenheit are prime conditions for swift bacterial growth, with bacteria counts potentially doubling in just 20 minutes, defining this range as the "Danger Zone."

Conversely, hot smoking simultaneously cooks and smokes the bacon. The temperature inside the smoker is raised to ensure the meat reaches an internal temperature of 155 degrees Fahrenheit. Selecting specific woods, such as apple, maple, or hickory, will determine the resultant flavor. Bacon that's hot-smoked is ready to be eaten immediately, presenting a firm texture ideal for immediate slicing.

Industrial production

The shift to industrialized bacon production has streamlined and standardized the curing process while preserving core principles. Wet curing, a prevalent method, uses a brine composed of water, salt, sugar, sodium nitrite, and additional flavoring agents. Rather than applying these elements externally, the meat is either submerged in the brine or directly injected with it, ensuring consistent flavor distribution and quicker curing. Sodium nitrite here also plays a dual role as a preservative and adding a signature pink shade.

Commercially produced bacon frequently undergoes a different process than artisanal varieties. Instead of traditional smoking which can span several days, an industrial approach involves placing the cured pork into a convection oven, a process that's notably swifter, clocking in around six hours. At this stage, liquid smoke is now commonly employed to expedite the flavoring process.

This method leads to a product that possesses higher moisture content and may exhibit a milder flavor profile. This augmented moisture inadvertently boosts the bacon's weight, subsequently elevating its price. Though industrially produced bacon may cost less per pound, you might actually be paying for added water, not more meat. The goal here is quantity and not superior quality.

The rise of uncured bacons

The shift towards more natural and organic foods has paved the way for the rise of uncured bacon. Unlike its cured counterpart that utilizes synthetic nitrates and nitrites for preservation, uncured bacon leverages natural nitrates derived from vegetable sources such as celery and beets. Due to the absence of artificial nitrates which accelerate the curing process, the pork belly in uncured bacon is exposed to the salt cure for a more extended period, often leading to a saltier end product.

From a safety perspective, the distinction between cured and uncured bacon can be minimal. Even with uncured bacon, consumers are still ingesting nitrates and nitrites, albeit from natural sources. According to Hone Health, "There is no scientific evidence that naturally occurring nitrates are any less likely to convert into cancer-causing nitrosamines in the body than sodium nitrate." This underscores the misconception that uncured means nitrate-free and thus healthier than regular cured bacon. In 2019, Consumer Reports revealed that meats labeled "no nitrites" utilized nitrites from natural sources like celery and, despite the source, contained similar levels of nitrites as those cured with synthetic versions.

Regarding taste and use in cooking, views are diverse. While culinary experts sometimes note subtle flavor distinctions between the two, many individuals find them similar enough to swap in various dishes. Their cooking characteristics, especially the way they crisp up, ensure both have a broad range of culinary applications.

Bacon's health profile

The nutritional profile of bacon is more complex than it might appear at first glance. When we break down a 4-ounce serving of cured bacon, it boasts a rich 15.5 grams of protein, and it's a source of essential nutrients such as various B vitamins, iron, magnesium, zinc, and potassium. These elements are crucial for maintaining good health, supporting metabolism, and aiding bodily functions.

Analyzing the fat composition of bacon, almost half of its fat content is monounsaturated, specifically the beneficial oleic acid, which is linked to heart health. About 35% is saturated fat, which, when consumed in large amounts, has been associated with increased risk factors for heart disease, according to MedllinePlus. However, the exact health implications of moderate saturated fat intake, especially when combined with an overall healthy diet, remain a topic of ongoing research. The remaining 15% of bacon's fat is polyunsaturated that, per Harvard Health Publishing, is known to reduce harmful LDL in the body.

The curing processes of bacon, whether dry or wet, inevitably result in a high salt content. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health warns that diet high in salt has its concerns: it has been linked to health issues such as stomach cancer, elevated blood pressure, and potential cardiovascular complications.

Sustainability and ethical considerations

Factory farming is one of the most widespread methods for raising pigs, aiming to maximize production while minimizing costs. In these setups, pigs are frequently housed in cramped conditions, often leading to various health problems for the animals. Beyond the ethical concerns about the animals' well-being, factory farming poses environmental issues. The method consumes significant resources, from the water to feed. Moreover, the runoff from these farms can contaminate water sources, and the operations contribute to methane emissions, a potent greenhouse gas. Both of these factors contribute to environmental degradation and can accelerate climate change.

Contrastingly, the free-range approach offers pigs a vastly improved quality of life. Within these systems, pigs can roam, graze, and engage with their surroundings, allowing them to exhibit their natural behaviors. This method, often referred to as pastured pig farming, generally has a lower carbon footprint. The pigs' manure acts as an organic fertilizer for the land. From a nutritional standpoint, bacon from pastured pigs tends to have higher concentrations of beneficial nutrients, including omega-3 fatty acids. Moreover, ethically raised pigs are less likely to receive antibiotics or growth hormones, resulting in a purer product. Not only do many consumers find this method more ethically sound, but many also assert that free-range bacon, due to the diverse diet and improved living conditions of the pigs, offers a superior taste.

Beyond pork

As consumers seek variety in their diets and alternative meat products for health, religious, or ethical reasons, the food industry has responded with innovative substitutes — like bacon not made from pigs. Beef bacon, for instance, is made by curing, drying, smoking, and then thinly slicing beef belly, creating a direct one to one substitute for its pork counterpart. Perfect for those observing pork-averse religious traditions.

Turkey bacon provides another meat-based alternative to traditional pork bacon. Its appeal lies in its nutritional profile: turkey bacon contains roughly 75% less fat and offers almost double the protein compared to pork bacon. Produced from a blend of dark and light turkey meat, it is seasoned and reshaped to resemble bacon strips.

Smoked salmon bacon, derived from the fatty salmon belly, offers a unique alternative in the world of bacon substitutes. Unlike turkey, salmon has the advantage of fat, albeit fish fat, which is fundamentally different from pork fat. However, fat translates to flavor, and for those who savor the rich taste of fatty salmon, this variant presents an enticing option.

Outside the box

Bacon, traditionally a breakfast staple, has infiltrated diverse realms of the culinary landscape. One such unexpected arena is the world of mixology. Bacon's savory and smoky profile has found its way into cocktails, specifically pairing with the rich, caramel notes of bourbon. This combination has garnered attention and become increasingly popular in bars and among mixologists, leading to a wave of innovative bacon-infused bourbon cocktail recipes.

The bacon phenomenon doesn't end with drinks. The flavor profile of bacon has been so widely adored that it has been adopted into a variety of snack and dessert products. Consumers today can find bacon-flavored gums that aim to capture its unique taste in chewable form. Additionally, popcorn, a beloved snack, now comes with bacon seasoning, providing an entirely new snacking experience. Even in the realm of desserts, ice creams have been infused with bacon, challenging traditional taste boundaries and offering a blend of sweet, creamy, and savory notes.