Crisco: 7 Facts About The Shortening Brand And Why People Stopped Using It

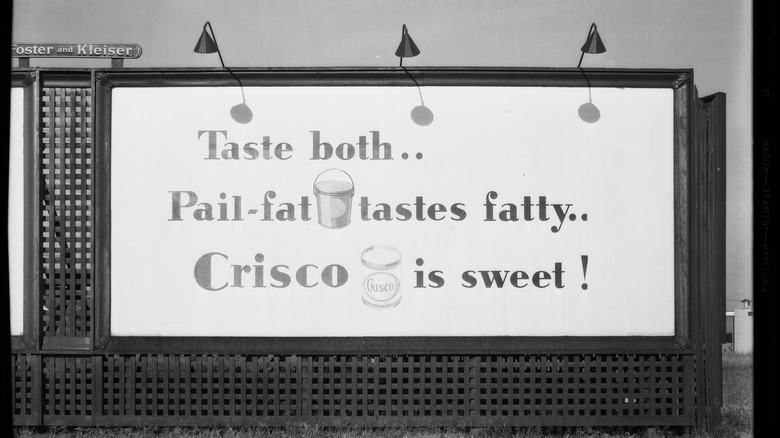

For over a century, Crisco has experienced a rise and fall in popularity, reflecting the American 20th century as an era of processed foods and targeted advertising. Incorporating innovative technologies to create "an absolutely new product," an announcement read at the time. Crisco was an early example of a brand becoming something consumers trusted more than the product itself, and its popularity was made possible due to the mystery surrounding what it was actually made from.

Both kosher and vegan, Crisco is a vegetable substance that paved the way for culinary possibilities, contributing a new dimension to fried foods and baked goods at a highly affordable price. A product that remained in surplus during Great Depression scarcity and wartime rationing, Crisco helped define American cuisine. But for all its innovations as a scientifically engineered substance, Crisco has lost some of its clout as more research has brought us a greater understanding of its health ramifications. Though we may know better now that Crisco isn't exactly healthful, it also isn't necessarily intended to be. So long as it isn't consumed in vast quantities, Crisco remains a pantry staple uniquely suited to cooking up the sweet treats and comfort foods it makes best.

1. The first vegetable shortening

Shortening is the American term for any form of fat used for cooking which exists as a solid at room temperature. Before the 20th century, butter and lard were the most common forms of shortening used in American households, and these were typically produced at home. While butter is made of churned cream from cow's milk, lard comes from pork fat — and according to the Oxford Companion to Food, "was an article of almost as much value as the meat" (via Food Timeline).

As the modernizing world of the 19th century moved further from agriculture, lard was among the many ingredients that became industrially produced. But in 1906, greater insight into meat manufacturing stigmatized lard as one of the major outputs of the meat-packing industry. This was the year that Upton Sinclair's novel, "The Jungle," was published in its entirety. Though the book was fictional, it portrayed some scary truths about the working conditions in Chicago's stockyards. The bestselling novel's horrifying tales of workers disappearing into vats of boiling lard were enough to bring purchasing animal shortening into question. But even though Sinclair's novel succeeded in exposing capitalist corruption and turning many people away from industrial meat processing, the novel's decrying of lard production's inhumane conditions created an ironic opportunity to devise a completely new product — vegetable-based shortening. Seizing this gap in the market, consumer goods company Procter & Gamble introduced Crisco to the public in 1911 with the emphasis that it was "purely vegetable."

2. It was invented by a soap company

As it turned out, Procter & Gamble's Crisco was the answer to both a shortage of shortening and a surplus of vegetable byproducts. Specializing in the production of soaps and candles, P&G had traditionally fashioned these bestsellers from lard and tallow, both meat byproducts. But to stray from the burgeoning meat industry stigma, the company began experimenting with cottonseed oil, another much cheaper manufacturing byproduct in ample supply through the United States' large-scale cotton industry.

P&G's new technology of hydrogenation — adding hydrogen to a liquid saturated fat to transform it into a solid — was successful in creating cottonseed oil-based candles. The substance was also technically edible and conveniently bore a resemblance to lard. The additional convenience was that the added hydrogen greatly extended its shelf-life — Crisco lasts a long time.

Having enough trouble getting households to believe in cottonseed oil candles (consumers were leery about using cotton products that were neither clothing nor linens), P&G's packaging didn't list Crisco's single ingredient. It wasn't until the 1960s that companies were legally required to list ingredients on product packaging — in the interim, Crisco remained an enigmatic substance. While consumers were reluctant to try a shortening made from partially hydrogenated vegetable oil – a new term referring to plant-sourced oils that Crisco helped make mainstream — they couldn't deny the superior baked goods and crisply fried foods that Crisco produced. Though its ingredients remained mysterious, the new shortening brand was soon in high demand.

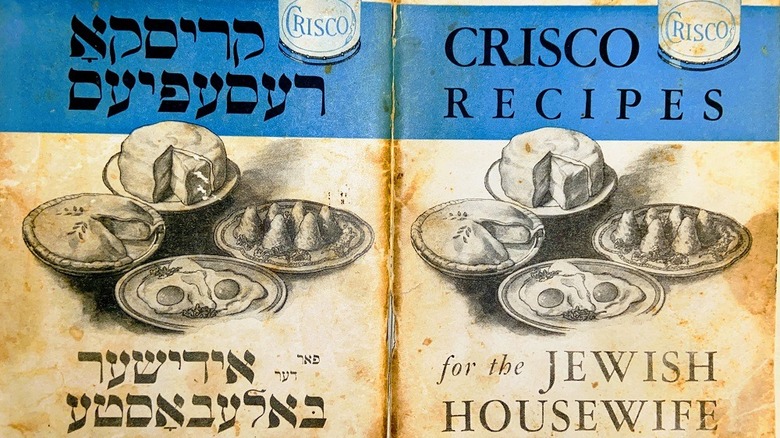

3. It found popularity in kosher households

Though the "absolutely all vegetable" advertising campaign kept many households suspicious about adding Crisco to their pantries, there were other demographics that embraced Crisco's novelty. Jewish immigrants were among the first to popularize Crisco, since the plant-based substance afforded new opportunities for kosher cooking. Instead of lard or butter, traditional Jewish cuisine relied on schmaltz, a substance similar to lard but made with rendered chicken fat. Crisco served as a cheaper and equally effective replacement for schmaltz, even making formerly forbidden food combinations kosher — more meals could suddenly adhere to the dietary laws of avoiding the preparation of meat and dairy in the same meal.

Recognizing the potential in catering to niche markets for their new product early on, P&G targeted Jewish consumers specifically. They hired rabbis to inspect their production facility, established advertising campaigns for Jewish newspapers, and sent cookbooks to Jewish households. P&G's 1933 cookbook "Crisco Recipes for the Jewish Housewife" suggests an interesting intersection of traditional Jewish cuisine and an Americanization of culinary traditions, including recipes like Southern fried chicken among more traditional fare, with each recipe printed in both English and Yiddish. Though Crisco, as a thoroughly modern ingredient, may not have been traditional itself, it was highly affordable and guaranteed not to be contaminated with potentially un-kosher additives. Whether or not people actually preferred this vegetarian substitute for schmaltz and lard, they quickly began buying it religiously — by 1917, Americans had purchased 60 million cans of Crisco.

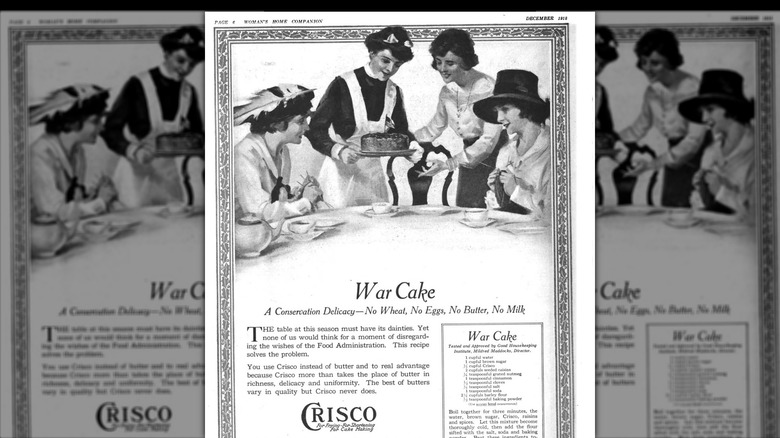

4. Crisco became a staple during both world wars

While early Crisco advertisements were targeting Jewish communities successfully, it took a more extreme campaign to grant the shortening brand mainstream commercial appeal. The onslaught of World War I brought about rationing for many pantry staples, and the U.S. government urged civilians on the home front to use alternatives. Rather than baking and frying with traditional shortenings like lard or butter, households were encouraged to cook with vegetable oils. Crisco was ready and waiting on grocery shelves, bearing a convenient textural similarity to the animal shortening patriotic households opted to forgo. During this time, P&G also published cookbooks that emphasized vegetable shortening's nutritional superiority and provided recipes for cooking anything imaginable with Crisco, making the brand seem like a smart culinary choice.

Crisco found an unexpected new purpose by the time WWII had come around. Amidst another wave of wartime rationing, there was enough of a Crisco surplus that it was employed in industrial quantities outside of the kitchen, too. Crisco's versatility as a substance met U.S. government specifications for a product that would not freeze or melt in different water temperatures. As a result, the P&G shortening brand found increased wartime demand as lubricant for submarine torpedoes. As Crisco became an important ingredient in the military industrial complex, it solidified equally as a fixture in American households, aided by another wave of Crisco cookbooks published during and after WWII that further highlighted the versatility of vegetable shortening.

5. Crisco makes superior pie crusts

Despite any contention over Crisco's nutritional shortcomings, it has always had a value of a different kind — it is a form of shortening that gives baked goods better texture. Many bakers to this day swear by using Crisco instead of butter as the key to success for certain treats, especially cookies and pie crusts.

As it turns out, it's simple science that makes Crisco a magical ingredient. Crisco is composed of 100% fat, whereas butter has a 10-20% water ratio. As a result, butter melts more readily when handled, which means dough made with butter sometimes results in a tougher pie crust. Crisco, composed of trans fats, melts more gradually as it bakes, because it has an inherently higher melting point. This means that there's less chance of overmixing or melting the fat in any dough made with shortening before it's in the oven. As a result, Crisco is known to produce a flakier pie crust.

Perhaps in hopes of converting purists who, irrespective of textural outcomes, find butter results in a tastier pie crust, Crisco introduced its butter-flavored shortening in 1981. While this combination may have been intended to serve as the best of both worlds, studies reported by the National Institutes of Health have revealed that butter-flavored products contain diacetyl, an unexpectedly deadly chemical. Whether prioritizing flavor or texture, it might be best to pick a side.

6. It was once part of a health push

From the start, Crisco was advertised as a healthier alternative to animal fats. Early campaigns to assert Crisco's nutritional superiority had no legitimate science backing them up, but did succeed in convincing consumers with an authoritative emphasis on Crisco's alleged digestibility. P&G asserted in its original cookbook, "The Story of Crisco" – first published in 1913 — that "four classes of people—housewives—chefs—doctors—dietitians—were glad to be shown a product which at once would make for more digestible foods, more economical foods, and better tasting foods." The book further asserts that Crisco's vegetable ingredients made it the "easiest of all cooking fats to digest."

The technology behind Crisco's hydrogenation was part of another health push many years later, when in the 1980s, health activists became advocates for partially hydrogenated oils. Also known as trans fats, these were believed to be a healthier alternative to the saturated fats found in palm or coconut oil. Activism in favor of hydrogenated oils led to the rise in margarine as an 80s health fad and put pressure on fast food chains to use hydrogenated oils in their recipes. It wasn't until the 1990s that further studies revealed trans fats were directly linked with increased bad cholesterol and heightened risk of heart attacks. This stigmatized Crisco and other hydrogenated oils in much the same way as lard had been villainized nearly a hundred years prior, causing consumers to seek out other forms of shortening once again.

7. Crisco changed its formula to be healthier

After the discovery that trans fats are linked with heart problems, consumers in more recent years have opted to use various substitutes for shortening. In order to compete, Crisco had to change its recipe. Since 2007, the brand has eliminated nearly all of the trans fats in its Crisco products. The new Crisco recipe has removed cottonseed oil from the equation, and the easily recognizable tubs of Crisco are now filled with a mixture of soy and palm oils. Rather than partially hydrogenated, today's Crisco contains fully hydrogenated oils, a process which, according to Michigan State University, returns substances to a point of zero trans fat. In reality, Crisco contains no more than 0.5 grams of trans fats per serving, a low enough amount that the Food and Drug Administration permits Crisco products to list zero trans fats on their packaging.

Despite this more health-driven shift, however, Crisco is still largely regarded with a stigma that has kept its popularity lower than it once was. Its use of more health-conscious vegetable oils has also contributed to a decline in its textural value as a form of shortening — according to some, today's Crisco has a tendency to liquefy if kept in too warm a temperature. As a solution, experts suggest keeping this newly formulated Crisco in the fridge. And even if the new and improved Crisco may appear, on paper, to contribute less directly to health risks, it is still probably best enjoyed in moderation.