The Ultimate Guide To The Oldest Known Cookbooks In The World

People in the ancient world loved fine food every bit as much as we do today, and they left behind tantalizing clues about it too. In June 2023, archaeologists unearthed an ancient Roman fresco in Pompeii that seems to show what might be an early ancestor of modern pizza. YouTube channel Tasting History managed to recreate the long-forgotten dish by examining the painting and filling in the blanks based on surviving historical records. Not all foods from the past are quite so difficult to make today, though. Fortunately, cookbooks are found in cultures around the world, and they have a much longer history than most people might realize.

Today, cookbooks are a common sight in many homes, from dusty old thrift-store finds to glossy coffee-table books full of appetizing pictures. Around 20 million cookbooks are sold in the United States alone every year. The first one written in a modern style is usually considered to be Eliza Acton's "Modern Cookery for Private Families," though the name is now slightly ironic given it was first published in 1887. A plethora of printed cookbooks already existed at the time, however, such as Amelia Simmons' book "American Cookery." Published almost a century earlier, in 1796, it's known as the first-ever American cookbook. But both of these are just a continuation of an ancient tradition, and the oldest known cookbook was written over 3,000 years before Amelia Simmons first put pen to paper.

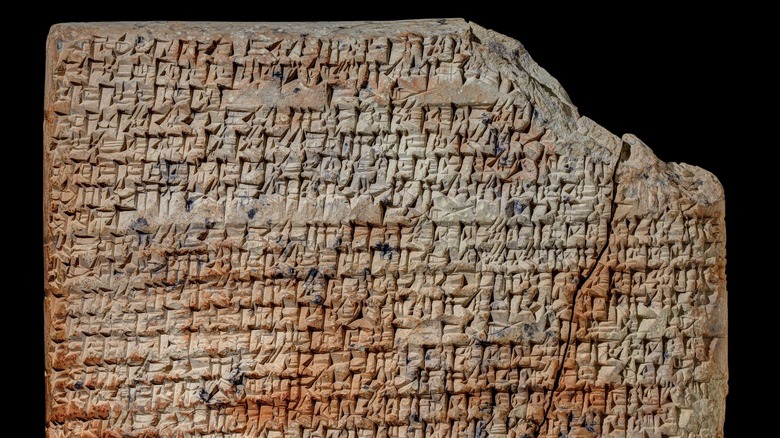

Yale Culinary Tablets

The world's oldest cookbooks aren't books at all, but cuneiform tablets from ancient Mesopotamia. Kept at the Yale Peabody Museum is an extensive collection of inscribed clay tablets dating back to the Old Babylonian period, and three of them contain recipe collections from around 1730 B.C. These are the Yale Culinary Tablets, and their translation can be found in a book titled "The Oldest Cuisine in the World: Cooking in Mesopotamia." The recipe collections written on them are seemingly unique, having never been found elsewhere.

These tablets were written by different people and were seemingly collected from at least two different origins. Containing details on both ingredients and cooking methods, all of them are damaged. The only tablet with remaining intact recipes is one with recipes for stews. The stew tablet also contains more recipes (25 in total), while the others list fewer dishes but include more detail. Four of the dishes are mostly vegetarian, except for the addition of animal fat.

Some ingredients are familiar in modern-day kitchens, like shallots and coriander seed, while some recipes seem extremely unusual, such as a broth made from sour milk and sheep's blood. Perhaps the most popular recipe in the collection is for a lamb stew, cooked with leeks and beets. Ancient Babylonian food was well seasoned, and this one includes garlic, onion, cilantro, cumin, and peppery arugula leaves. Additionally, this stew is one of a few recipes to include a cup of another ancient Mesopotamian staple — beer.

De Re Coquinaria

The book "De Re Coquinaria" is often translated into English with the title "Cookery and Dining in Imperial Rome," though the name literally translates as "The Art of Cooking." It's the oldest surviving intact collection of recipes in the world. The ancient Romans famously enjoyed lavish feasts and indulgent foods, and the variety in this book is enough to keep any kitchen enthusiast busy. The book is sometimes referred to simply as "Apicius," after the first-century Roman gourmet Marcus Gavius Apicius, who's usually credited as the book's author. It contains recipes ranging from a simple spiced wine to elaborate roasted meats.

Rather than a single book, it's actually a collection of 10 books that were seemingly compiled sometime around the fifth century, with around two thirds of the collection being Apicius' original recipes. In total, the collection contains around 500 recipes, though it doesn't mention any quantities for the ingredients, seemingly leaving that to the judgment of the chef. Roman foods were also well seasoned, frequently with spices like pepper and cumin as well as herbs such as mint and celery seed. Many also include ingredients that would've been common in Roman kitchens but are essentially unknown today, such as a thick grape juice reduction called defrutum and a fermented fish sauce called garum — though the latter could possibly be substituted with the fish sauce used in Southeast Asian cooking. Other ingredients are now impossible to find, like an herb called laser which is an extinct ancient plant.

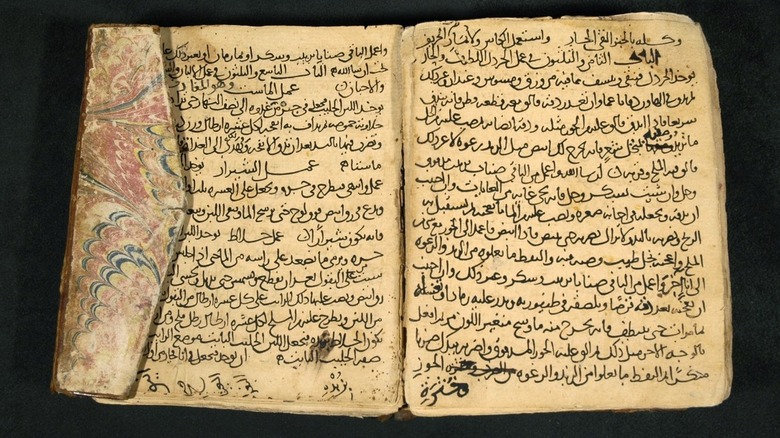

Kitab al-Tabikh (10th century)

Also transliterated as "Kitab al-Ṭabīḫ," this collection of recipes was compiled by an Arab noble named Abu Muhammad al-Muthaffar ibn Nasr ibn Sayyār al-Warrāq. Containing over 600 recipes, the name means "The Book of Dishes," though the best-known English translation has the title "Annals of the Caliphs' Kitchens." Medieval Arab cuisine was seemingly quite different from the food eaten in the modern-day Middle East. Many of the recipes in the "Kitab al-Tabikh" use plentiful amounts of herbs, such as basil, parsley, mint, and tarragon. While alcohol is typically prohibited in the halal diets of modern Muslims, this book also includes instructions on making grape wine and date wine, as well as mentioning wine as an ingredient in some recipes.

In medieval times, Baghdad was a city rich in culture and diversity, and this is reflected in the way the book is presented. More than simply a cookbook, the "Kitab al-Tabikh" is a celebration of food. Some dishes, like an open-faced sandwich called a mashtur, even come with their own poems. While this may have been before the time of famous names like Hafez and Rumi, the Arab world has always had a strong poetic tradition and the caliphs were fond of entertainment at dinner time, sometimes encouraging guests to recite poetry about the meals in front of them. In the medieval Islamic world, people loved good food and made certain to share that love around.

Kitab al-Tabikh (13th century)

It's easy to be confused by the fact that there are actually two medieval Islamic cookbooks with the same name, but they were written a few centuries apart. The second "Kitab al-Tabikh" was compiled in 1226 by a Muslim scholar, Muḥammad bin al-Ḥasan bin Muḥammad bin al-Karīm al-Baghdadi, usually referred to simply as al-Baghdadi. The original manuscript is kept at the Süleymaniye Library in Turkey, but an English translation can be found under the slightly unexciting name of "A Baghdad Cookery Book."

One ingredient used often in this book is called murri, a type of condiment made from fermented barley, with a similar flavor to soy sauce or Japanese miso. While murri may have fallen out of favor in the modern world, there are several other recipes in this book that are still often enjoyed today. One is an early version of hareesa, a type of slow-cooked overnight stew made with cracked wheat. Another is a popular comfort food in the Middle East, called mujaddara. Easy to prepare and satisfying, it's made with spiced white rice and green lentils, topped with caramelized onions and a little sour cream. The "Kitab al-Tabikh" contains the first recorded recipe for the dish, and the modern version is essentially unchanged from the dish enjoyed centuries ago.

Wushi Zhongkuilu

The "Wushi Zhongkuilu" was written in the early 13th century, during China's Song dynasty. It's the oldest known Chinese cookbook written by a woman, though its author is a little mysterious, known only as Mrs. Wu. The title is sometimes translated as "Madame Wu's Manual on Cuisine," and it shows a lot of influence from cultures on the Western side of Asia, particularly Muslim cuisine. Remarkably, one of the recipes it contains is named "little pressed short-pastries" and is a doughnut-like dish virtually identical to churros! With the Silk Road running from Baghdad to China around the time this book was written, it makes sense that many people would have enjoyed some foreign cuisine in their diets, much as we still do today.

Madame Wu does also include some distinctly Chinese recipes, though. Notably, this book contains some of the oldest written references to soy sauce, though the book is so old that it calls it by a slightly different name. Despite quirks like this, some of the recipes in this medieval cookbook wouldn't be out of place on a modern menu, like stir-fried meat marinated in soy sauce, or crab cooked in wine, soy sauce, and sesame oil.

Shanjia Qinggong

Considered an iconic cookbook from the Song dynasty, the "Shanjia Qinggong" was first written in the 13th century by a hermit named Lin Hong. The name loosely translates as "Simple Foods of the Mountain Folk," and the book includes a number of vegetarian dishes from the Tang dynasty. This book left a permanent mark on Chinese cuisine, and its influence can still be seen in modern Chinese vegetarian food. Another translation for the title is "Pure Offerings in the Mountains" from the word "qinggong," which is often understood to mean purity and usually carries the implication of vegetarian food. While that suggests it's specifically a vegetarian cookbook, it does contain dishes made with meat, as well as alcohol.

While many of the world's oldest cookbooks feature grandiose dishes to serve to kings and nobles, this book is all about simple, wholesome cuisine. Quite minimalist in its style, these dishes are nutritious and made with seasonal vegetables — specifically using local produce grown in the mountains. They may be simple, but several recipes are still quite aromatic, with ingredients like plums, tangy citrus, and sandalwood. Some, however, seem quite bizarre. The book contains one notable recipe for a dish called "pebble soup," which involves taking mossy white pebbles from a running stream, adding spring water, and boiling them to produce a broth.

Anonymous Andalusian Cookbook

Known only as the "Anonymous Andalusian Cookbook," this text was written in medieval Spain, when most of the Iberian Peninsula was a Muslim kingdom known as Al-Andalus. As a result, the Islamic flavor of this cookbook is unmistakable, and it also includes some cuisine from the Maghreb in North Africa. This influence shows in some of the ingredients used in the dishes; as in the "Kitab al-Tabikh," murri is mentioned in several recipes, and the book also includes advice about the best kind of murri to use.

This cookbook is one of the largest surviving recipe collections from the medieval world, with instructions to make over 1,000 dishes. As you might expect from such a comprehensive collection, there are various recipes for all kinds of foods. There are entire chapters devoted to breads, bread puddings, rice dishes, and pastries. It also includes several recipes for non-alcoholic drinks including violet syrup, as well as syrups made from things like lavender, pomegranate, citron leaf, and even thistle. It also places a lot of importance on health, including instructions for healthy cooking and hygiene, as well as chapters on medicines and medicinal dishes, with one chapter full of foods to serve to those with a weak stomach.

[Featured image by Alex Kulikov via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Liber de Coquina

Historic cookbooks often had quite simple names, and the "Liber de Coquina" was no exception, with a title simply translating as "Book of Cooking." The manuscript was written in 14th-century Europe and is currently kept in Paris, at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, where it's composed of two parts, known as "Tractacus" and "Liber de Coquina." This pair of texts are written in Latin, and they weren't originally French, having seemingly been written somewhere in Southern Italy. They may have been used by the nobles of the Kingdom of Sicily.

The book suggests that its author was either well-traveled or at least well-read about customs elsewhere in Europe, mentioning styles of cuisine from England, France, and even Roman traditions. The recipes in it are quite simple, giving a window into the medieval European diet, from legumes like chickpeas to roasted meats. Some of the seasonings may seem a little unusual to the modern palate, though, such as using saffron to season fried chicken, or baking a pie of poultry and sour grapes. It also contains recipes to cook some birds that aren't on the menu at all in modern times, like peacock and crane.

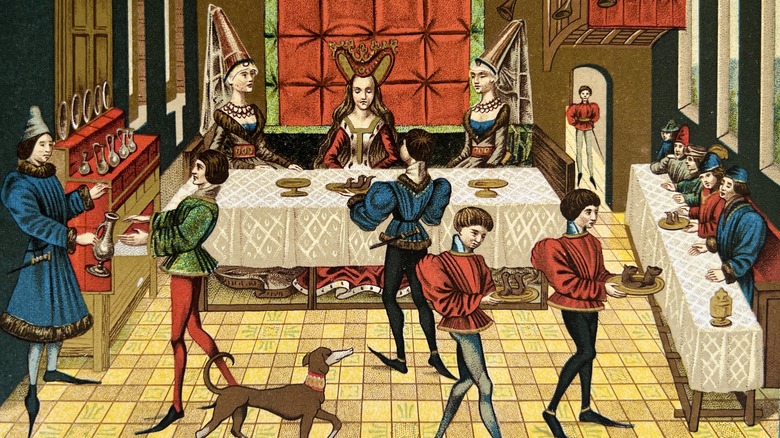

Le Viandier

Written around the turn of the 14th century, "Le Viandier" (meaning "The Food Provider") is an old French cookbook. French cuisine has a sturdy reputation among the culinary traditions of Europe, and that's thanks in no small part to the legacy of this book and the fame it enjoyed centuries ago. "Le Viandier" was compiled by a chef named Guillaume Tirel under the alias of Taillevent, and has instructions for making a variety of traditional French foods. There are several recipes for pottage, a kind of thick stew still eaten in France today, though the seasonings are quite different from those used in modern French cuisine. These medieval pottages were made with spices like cumin, ginger, cinnamon, and saffron. It also includes several seafood dishes and, perhaps surprisingly, some rice dishes. One, called Ris Engoule, is a wholesome dish of rice boiled in beef broth, and it seems like a medieval version of the risotto enjoyed in modern Italian cuisine. While, for the most part, we may not associate rice with European cuisine today, it first became popular in Europe during medieval times, thanks to the Arab influence on Spain and Southern Italy.

[Featured image by Darka66 via Wikimedia Commons | cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Utilis Coquinario

The "Utilis Coquinario" dates back to the 14th century, and its name loosely means "Useful for the Kitchen." Its author is unknown, but the original text is written in Middle English, making it one of the oldest known English cookbooks in the world. This is another book with recipes clearly intended for nobility, with one specifically mentioning serving it to a lord. Several of the dishes are extremely elaborate, with recipes for waterfowl such as swan and heron. It shows some influence from medieval French cuisine, and it's also explicitly a Christian cookbook, including mentions of festivals like Lent.

Some of the recipes in this book are what you might expect from medieval cuisine, with dishes like meat pottage and roast duck. Some other dishes seem a bit more surprising, though, like one for sweet and sour fish and a dish of rice and almonds called blawmanger. Most notably, though, it contains recipes for almond milk, as well as almond cream and almond butter. While we may think of it as a rather modern thing to keep in the kitchen, almond milk was a very popular ingredient in medieval times!

Llibre de Sent Soví

The "Llibre de Sent Soví" was first compiled in the early 14th century and was originally written in Catalan. Like several medieval texts, it was compiled by an anonymous author, and probably contains the work of several different people. It contains a few mysteries, though, and one is the title — the exact meaning of the name is unknown. Being collaboratively written, it's also difficult to pin down what the definitive original version may have been, if such a thing can even be said to have existed. The concept of an original version doesn't quite fit with medieval cookbooks, which were usually considered works-in-progress, continually updated by successive authors. At least one author of this book lays claim to some high credentials, though — whoever wrote the introduction mentions having cooked for the king of England.

This cookbook contains a few seafood dishes, like one for squid stuffed with onion, garlic, raisins, and spices. At the time, squid was considered a poor people's food, which suggests that at least some of the recipes included here were intended for common people rather than wealthy nobles. It also contains recipes for a few condiments. One is a kind of garlic and goat cheese sauce called almadroc, while another is quite similar to mayonnaise or aioli, made with olive oil, eggs, and a generous amount of garlic. Among the dessert dishes is an early recipe for crema catalana, a Catalan version of crème brûlée.

Yinshan Zhengyao

While many old cookbooks were full of lavish, indulgent recipes, the "Yinshan Zhengyao" is one that was specifically intended to be about healthy eating. With its title meaning "Correct Preparation and Application of Delicious Broth," it was written by a court physician by the name of Hu Sihui, and the whole book is dedicated to a special therapeutic diet intended for the 14th-century Chinese emperor Renzong.

The book is now considered as much a medical text as it is a cookbook, full of information on traditional Chinese medicinal herbs and drugs. With its strong emphasis on diet and healthy eating, the soups and other dishes described in the book were specifically created as medicinal treatments without sacrificing flavor. In Chinese medical tradition, a good diet has long been considered the most important kind of health care, and Hu Sihui was tasked with creating dishes that maintained this vital therapeutic function while also being quite literally fit for a king. Interestingly, several well-known Asian foods were originally created to be eaten medicinally, including Chinese jiaozi dumplings.

Das Buch von guter Speise

With its title meaning "The Book of Good Food," this may be the oldest known German cookbook, dating back to around A.D. 1350. It's another book intended for the upper class, showcasing the kind of haute cuisine once enjoyed by nobility. This book was originally two volumes, but unfortunately, most of the first volume has been lost. Only six pages of it remain. All the same, it still contains a respectable 101 recipes.

Some of the dishes contained in "Das Buch von guter Speise" are exceptionally indulgent, with recipes such as deer liver in honey sauce, fish and apple tart, and roasted pears with honey filling. A few items in the book also have comical twists, like a dish called "a clever food of plums," and a couple are just joke recipes, clearly written to be absurd. Alongside all of the food recipes, it also includes detailed instructions on how to make a good mead. For anyone who enjoys homebrewed beverages, this will give a true taste of the kind of mead enjoyed in medieval times.

The Forme of Cury

First written near the end of the 14th century, specifically to compete with "Le Viandier," "The Forme of Cury" is probably the most famous medieval English cookbook, compiled by the master cooks of Richard II. The name means "The Method of Cooking" and, despite the title, it doesn't actually have anything to do with curry. That said, like many other medieval cookbooks, it includes several recipes for well-seasoned dishes, incorporating many of the same spices used in South Asian cuisine, including coriander seed, ginger, cloves, and galangal. At the time, spices like these were expensive luxuries, only used on special occasions, and the heavily spiced dishes in this book were intended to be served at banquets. At the same time, many of the recipes included here were simple, everyday household dishes, which the book explains should be cooked "craftily and wholesomely."

"The Forme of Cury" is the oldest known cookbook to include ingredients such as olive oil and cloves in English cuisine. It also contains an old recipe for Christmas pudding, but since it's written in Middle English, it's a little difficult to read. Named "fygey" (as in "figgy pudding"), it's made with ground almonds, wine, and honey, as well as raisins and quartered figs. At the time, these would have been indulgent ingredients to use in English kitchens. It's understandable, then, that a recipe like this would be reserved for special occasions.