The Competitive Origin Of Pineapple Upside-Down Cake

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

If you've ever been to a potluck dinner or a family holiday gathering, there's a good chance you've had pineapple upside-down cake. This ubiquitous dessert, which commonly uses canned pineapple, has been served to hungry Americans for a century or more. In 1983, the Scrantonian Tribune called it an "all-American-a classic dessert," noting how people fondly remembered the recipes of their mothers and grandmothers.

Today, a simple Google search for "pineapple upside-down cake recipes" yields more than 3.2 million results, helping in its own small way to fuel a global canned pineapple market expected to grow at a compound annual rate of 5.5% through 2030 (via DATAINTELO). It even has its own day on the calendar: April 20 is National Pineapple Upside-Down Cake Day, though when the day received this designation is unknown.

The story of the pineapple upside-down cake is as tasty and juicy as the dish itself. Ironically, for a dessert and fruit associated with hospitality and welcomeness, this cake owes much of its popularity to a recipe contest that was part of a pineapple marketing campaign in the 1920s. So how did a competition help give us something that Betty Crocker declared a "must-make favorite for generations"? Let's look at the history of pineapple upside-down cake — preferably with one baking in the oven.

Upside-down desserts have been around for a long time

We should start by noting that the story of the upside-down cake doesn't begin with pineapple — or even cake, for that matter. Food historian Dr. Bert Gordon notes that, while the term "upside-down cake" was first used around 1870, the style of cooking dates back as far as the Middle Ages. In those days, upside-down desserts were mainly pies and tarts. Per the Food Timeline, modern cake as we know it with refined flour and baking powder didn't appear until around the mid-19th century. (Although cake has existed for centuries, the earliest versions bore more of a resemblance to bread.)

When upside-down cakes first appeared, they were made using a wide variety of fruits. The Scrantonian Tribune says that several cookbooks published around the turn of the 20th century included recipes for upside-down cakes, including desserts with apples and cherries. And in 1923, both the Pittsburgh Press and the San Francisco Chronicle published recipes for prune upside-down cake. Although it's widely accepted that pineapple has usurped them all as the most popular fruit in upside-down cakes, others are still used today. In 1977, noted food writer Cecily Brownstone even wrote about using pears and chocolate cake batter to create an inverted cake.

What is an upside-down cake, anyway?

You can probably guess from the name that upside-down cakes are made a little differently than right-side-up cakes. With an upside-down cake, you put the toppings at the bottom of the pan, then flip the cake over after taking it out of the oven (or just serve it directly from the pan). The basic process involves melting butter and sugar in a pan, adding fresh or canned fruit (sometimes with the syrup) then carefully pouring cake batter over it.

Why would you want to do this? As the cake bakes, the sugar, butter, and fruit all caramelize to form what becomes a topping after you turn it over. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette once referred to it as a "self-decorating cake," though many recipes include the option for whipped cream or some other garnish. The remaining juice from the fruit also runs down and helps keep the cake moist.

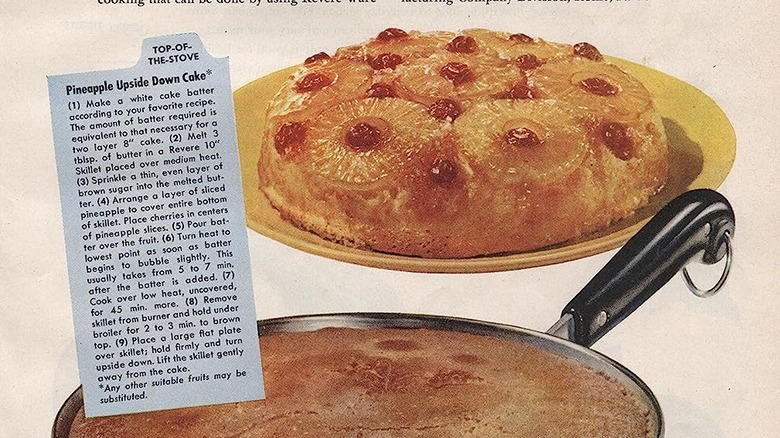

There's also the matter of how one cooks an upside-down cake. They originated in an era before ovens became widely available and reliable. As such, many people cooked cakes and other desserts in skillets on a stove or over coals. Before the current moniker came about, they were commonly known as "skillet cakes." Some also called them "spider cakes" because early cast-iron skillets had spider-like legs so they could stand freely. By any name, they were an accessible way for common folks to enjoy an easy-to-prepare sweet treat.

Where did the pineapples come in? A very brief pineapple history

Now there's the matter of how pineapples entered the cake equation. The modern pineapple market is huge, with Mordor Intelligence reporting that 28.6 million metric tons were produced in 2021 alone. But it wasn't always such a common fruit. In the 16th and 17th centuries, pineapples were primarily seen as a status symbol due to their scarcity. A single "King Pine" could cost thousands of dollars, so simply being able to afford one was a big deal. Many people who owned a pineapple didn't even eat it — they just brought the pineapple to events until it rotted.

But by the 19th century, efforts were well underway to mass-produce pineapples. Spain introduced the fruit to Hawaii in the late 18th or early 19th century, with the first written record being a diary entry by Spanish sailor Don Francisco de Paula Marin in January 1813 (via Smithsonian Magazine). It spread rapidly throughout the islands, and in the early 1850s, pineapples were briefly a commercial crop to help feed prospectors during the California Gold Rush.

Commercialization attempts were renewed in the mid-1880s, with British sea captain John Kidwell starting a multi-acre farm and eventually adding a small cannery to preserve his crops. Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, Britain was now importing steamships full of pineapples from its colonies. Prices fell substantially as a result, meaning more people could buy (and eat) the fruit.

James Dole spearheaded the canned pineapple boom

Although pineapple was trending towards the mainstream, one man would give us the final push that ultimately led to pineapple upside-down cake. Massachusetts native and businessman James Drummond Dole moved to Hawaii in 1899, planning to grow coffee beans. However, when this proved not to be feasible, Dole switched gears and formed the Hawaiian Pineapple Company in 1901. He didn't know a thing about canning at the time, but he did know it would be crucial for pineapple to be produced and used on a large scale.

Dole's new venture operated at a loss in the early years. This was partly because he was exploring new technologies and partly because he was having trouble finding investors for the company. Even his second cousin Sanford Ballard Dole, who was named the inaugural U.S. territorial governor of Hawaii in 1900, decided not to invest.

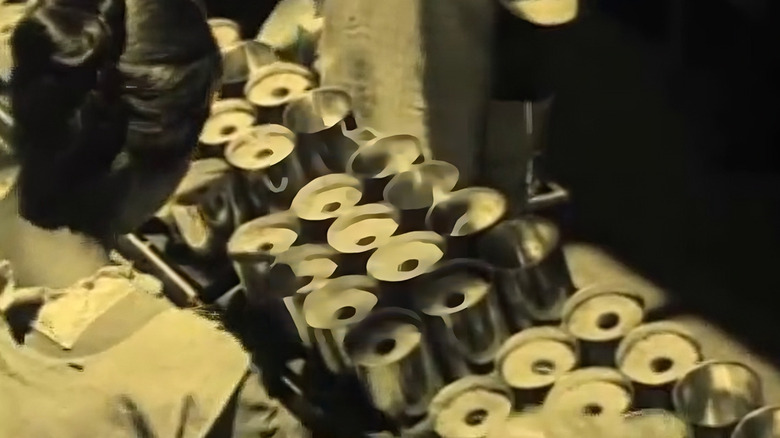

But a breakthrough came in 1911 when company employee Henry Ginaca invented a machine that automated the peeling, coring, and slicing of raw pineapples. Initially, it could process 35 pineapples per minute. After a little fine-tuning, that number rose to 100, a gigantic increase in production capacity. All workers then needed to do was remove any imperfections, and the sliced pineapple was ready for canning and shipment.

Dole also invested heavily in marketing and infrastructure

However, simply being able to produce more pineapple wasn't enough. Dole also needed to meet demand — and make sure that demand was there in the first place, which wasn't a given after the Panic of 1907 weakened pineapple sales in the continental U.S. But while Dole wasn't the first to sell canned pineapple, he understood perhaps better than anyone the importance of marketing it. To that end, he formed an association of fellow growers and put together a large-scale campaign aimed at driving demand back up and extolling the quality of Hawaiian pineapple. His work is widely credited with reviving people's interest in the fruit.

Dole was responsible for many other changes, too. Among other things, he introduced paper mulch to stimulate healthy fruit growth, motorized trucks for transportation, and sulfate spray as a fungicide. In 1922, he even bought an island (Lanai Island, to be exact) solely to set up a 20,000-plus acre pineapple plantation.

His work paid off in spades. Total production of canned pineapple rose from 243,000 cases in 1909 to 1,775,000 cases in 1920, an increase of 630% in 11 years (via The Hawaiian Journal of History). The Hawaiian Pineapple Company was the world's biggest of its kind by 1923, and pineapple had become a culinary craze that even the working class could afford. Known a century later as the Dole Food Company, Dole's venture remains one of the world's biggest pineapple traders, along with Del Monte, Fyffes, and Chiquita.

A Dole-led contest put pineapple upside-down cake on the map

This leads us, finally, to the origin of the pineapple upside-down cake. The marketing work of the Hawaiian Pineapple Company didn't stop when they reached the top. In 1925, they ran a contest to collect recipes for a forthcoming cookbook called "Pineapple as 100 Good Cooks Love it" (via Scrantonian Tribune). A panel of food experts would judge the recipes and select 100 for the book. Winners would also get a $50 cash prize.

Despite only advertising the competition once in a handful of women's magazines, the contest was a rousing success, with a whopping 60,000 submissions. What's more impressive, though, is that 2,500 of the recipes — more than 1 out of every 25 — were for some form of pineapple upside-down cake! That means that, less than two decades after pineapple demand was on the decline, people across America had come up with a similar take on a traditional dessert.

Ultimately, the pineapple upside-down cake recipe published in the cookbook was the one submitted by Mrs. Robert Davis of Norfolk, Va. Never one to pass up a marketing opportunity, Dole then ran a series of ads talking about how many people had sent in their versions of the recipe. This further fueled the popularity of pineapple upside-down cakes. You could say it was the 1920s equivalent of going viral.

But no one knows who really invented it

So we know Mrs. Robert Davis's recipe is the one that became the standard-bearer for pineapple upside-down cake. Unfortunately, we may never be able to pinpoint when, where, and who the first cake came from. With 2,500 pineapple upside-down cake recipes submitted, clearly a lot of people had thought of the idea by the time the contest took place, making it harder to narrow down the exact heritage.

The subsequent cookbook wasn't even the first time a pineapple upside-down cake recipe appeared in print. Per Quaint Cooking, the two earliest known recordings of this dessert come from a Seattle charity cookbook in 1924 (referred to as Pineapple Glacé) and a Gold Medal Flour print ad in 1925. The Boston Globe also published a recipe for pineapple upside-down cake on December 21, 1925, though it's unknown whether this came before or after the recipe contest. Ultimately, the best estimate we can come up with is that the cake was born sometime between 1911 (when Henry Ginaca invented his new pineapple corer/peeler) and the publication of the 1924 cookbook.

The cake continued to rise in popularity through the mid-20th century

Regardless of where it came from, it didn't take long for pineapple upside-down cake to spread far and wide, appearing in more and more publications. The Farmer's Wife published a recipe for it in their October 1926 issue. In the coming years, the cake was also featured as part of ads for Crescent baking powder, Spry vegetable shortening, and the Pineapple Growers Association. Other fruit makers jumped on the bandwagon as well, such as Hunt's Peaches, which touted a peach upside-down cake.

By 1969, Betty Crocker had even created a pineapple upside-down cake mix that came with a can of Dole pineapple slices (via Pinterest). Along the way, the pineapple upside-down cake almost single-handedly changed the perception of this cake style. As previously discussed, upside-down cakes were traditionally made by people who didn't have access to an oven. But Quaint Cooking notes that, with pineapples being trendy, the upside-down cake took on a more elegant aura. No longer was it a simple treat you threw together; it became something families brought out on special occasions. It's not unlike how avocado has become a more upscale food in recent years.

There are many upside-down cake recipes now — but you can still make the classic Dole version

We mentioned at the beginning how you can find a plethora of recipes for pineapple upside-down cake nowadays. There may not be millions of unique versions, but there are a lot of ways to enjoy it. Duncan Hines has a cake mix for a double-layer pineapple upside-down cake, and some people infuse it with rum for an adult version during the holidays. You can add pumpkin spice and other fruits. Other chefs make mini upside-down cakes in small skillets so people can have a single-serve dessert. The ease and versatility are part of why it's remained a dessert staple.

Nevertheless, we think you owe it to yourself to try the cake that Mrs. Robert Davis made famous in 1925. Thanks to Dole, you can still use the Classic Pineapple Upside-Down Cake recipe in your kitchen. It involves nine pineapple slices, maraschino cherries to plug the centers, chopped pecan nuts for some crunch, and whipped topping to finish it off (and cover any mistakes). We're getting hungry just typing all that. If making cake batter from scratch sounds too complicated, Dole now has a contemporary recipe that uses cake mix instead.

It's part of baking and popular culture to this day

Although it's been nearly a century since pineapple upside-down cakes officially entered the national lexicon, they have remained part of American culture. They're still regularly served at potlucks, parties, and bake sales, especially in the Midwest. And in 2014, the Tennessean wrote that the upside-down cake was having a "retro revival."

Above all else, the combination of a classic cake and fruit topping adds a nostalgic factor to desserts. It's also something passed down through generations: Debby Segura once wrote for Aish that one of the last things her grandmother wrote down was her pineapple upside-down cake recipe. While that cake was primarily served for birthdays, upside-down cakes are also popular during the holiday season, with King Arthur Baking Company among those touting such a recipe.

The cake has returned to its competitive roots, too. "The Great British Bake-Off" regularly holds an upside-down cake challenge and has published several of the recipes, including one from celebrity chef judge Paul Hollywood and another from Season 11 finalist Laura Adlington. The challenge even led to drama in the first episode of Season 11, when contestant Dave Friday had some of his pineapple upside-down cakes knocked over by another contestant trying to shoo a fly away (via The News). All was well that ended well, though, as Dave ultimately made the finals alongside Adlington and winner Peter Sawkins.

Some people see the cake a little differently, though

Of course, seemingly no food item would be complete without an alternate interpretation or two. Just like pretzels supposedly symbolize a person praying, and eating 12 grapes at midnight on New Year's Eve is supposed to represent good fortune for the year ahead, some people claim pineapple upside-down cake has meanings beyond that of a tasty treat.

This primarily has to do with the cake's inverted nature. An upside-down pineapple has been co-opted as a symbol in the swinger community, identifying oneself as a swinger looking for a party. Cruise Mummy claims swingers adopted this because pineapples and pineapple upside-down cakes are symbols of hospitality and friendliness, which swingers need to have as part of their activities. Whether the origin story is true or not, it's been accepted as such, with Susquehanna Brewing Company even producing Pineapple Upside Down Cake Imperial Shandy, a beverage that makes someone "sweet enough to take home."

SDLGBTN writes that others see pineapple upside-down cake as a sign of homosexuality and queerness. Supposedly, because the cake is made upside-down and frequently topped with whipped cream or ice cream, this makes it an LGBT dessert. The writer concludes that this is just a theory with no concrete evidence behind it. As for us, we say a dessert can mean whatever you like, as long as it tastes good and isn't harming anyone.

Upside-down cakes are found around the world

Cooking cakes the wrong way up isn't just an American thing. We already wrote about "The Great British Bake-Off" adopting the upside-down cake for 21st-century competition. But there's plenty of other inverted baking beyond U.S. borders.

Most notably, the French Tarte Tatin precedes the pineapple upside-down cake by about four decades. Friends of the Tarte Tatin writes that this fruit tart, which is essentially an upside-down apple pie, was created in the early 1880s at a hotel run by sisters Stéphanie and Caroline Tatin, whether deliberately or via happy accident. Like the pineapple upside-down cake in America, the Tarte Tatin has become synonymous with France. A book called "La Tarte Tatin – Histoire et Légendes" (Tatin Pie – History and Legends) was even published in 2011, though it currently can only be read in the French language.

The pineapple upside-down cake has been embraced elsewhere, too. A favorite dessert in Portugal is Bolo de Ananás, which is their version of the famous American cake. It's sometimes called Azorean Pineapple Upside-Down Cake, referring to the Azores Islands, which are home to the Augusto Arruda Pineapple Plantation. This adaptation stands out for its use of actual caramel sauce to caramelize the pineapple.

Other global inverted desserts include mango upside-down cake from Brazil and apple and pomegranate upside-down cake from the Philippines. Basically, almost wherever you travel, you can find cakes that are made upside-down and taste oh-so-right.