13 Discontinued Beers We Aren't Getting Back

The United States is a melting pot — a nation of immigrants — and that's clearly reflected in the country's history of beer. Cultures from all over the world came to America and brought their beer traditions with them, which eventually inspired regionally popular and nationally dominant breweries. Thanks to those pioneers and over the last couple of centuries, beer has become a quintessential American drink: Something to enjoy at the end of the day to relax, a beverage best imbibed with friends or as party fuel, and leading to the artistic and wildly creative craft brewing movement.

Millions of people love beer, and it's a big industry with a long history. But in history, there are always winners and losers, and not every beer brand or variety can rise to the level of Budweiser, Miller, Coors, Samuel Adams, or Sierra Nevada. Some beers that were once extremely popular (or which at least made a big splash on the scene for a while) simply fell out of favor and vanished, never finding their way into a bottle, can, or keg again. Here are some intriguing discontinued beers that have been lost to time.

Meister Brau

Reduced-calorie or "light" beers are commonplace today, and they date back to the 1960s. In 1967, according to VinePair, Rheingold Brewing Company biochemist Dr. Joseph L. Owades devised a method to remove starch from beer, creating a beverage that maintained the alcohol content and flavor but offered far fewer calories and carbs. Taken to market as a weight loss aid called Gablinger's Diet Beer, the product quickly failed, and Owades received permission from Rheingold to take his recipe to the Chicago-based beer company Meister Brau. That brewery marketed the same concoction as Meister Brau Lite with the slogan, "The Lite and Lusty Beer."

Meister Brau, focusing on the demand for reduced-calorie products (diet sodas were just starting to emerge as a viable, mass-market product in the late 1960s and early 1970s) used Meister Brau Lite as the linchpin of Lite Food Products, a line of healthy-skewing foods for the weight-conscious. But that expansion was too ambitious and not nearly successful enough. The entire brewery went bankrupt, and in 1972, the Miller Brewing Company acquired the recipe for Meister Brau Lite. After months spent altering and improving the recipe, it unveiled the beer with a new name: Miller Lite.

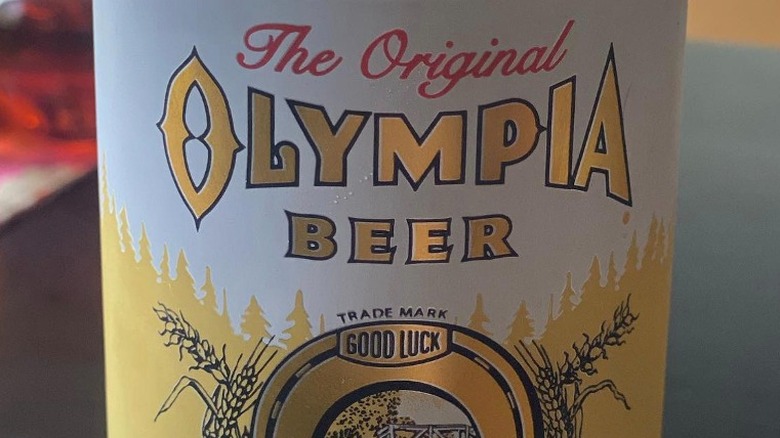

Olympia Beer

While light-tasting, lightly-colored, smooth-drinking lager-type beers have been a consistently popular choice in the United States for decades, individual favorites across the country have varied by region. In Washington state and surrounding areas, Olympia Beer was omnipresent for most of the 20th century. According to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, German immigrant Leopold Friederich Schmidt made traditional beer at the brewery he opened in 1896 in Tumwater, Washington (near the Washington state capital of Olympia).

Known for its marketing catchphrase, "It's the water," which referenced the artisanal, specially treated water that served as the basis of its flagship product, Olympia pumped out beer in Tumwater until 2003, when the Pabst Brewing Company acquired the company and moved production to California. In January 2021, Pabst Brewing decided to stop producing Olympia Beer altogether, citing "a growing decline in its demand" in an official statement on the brand's Instagram page.

Pete's Wicked Ale

Craft beers are produced in much smaller quantities than the competition, lovingly made in a multitude of seasonal varieties by small companies and distributed to limited areas. These brews tend to have a high alcohol content and pack a wallop of flavor, and the whole scene exploded in the late 1980s and early 1990s thanks to pioneering beers like Pete's Wicked Ale. In 1979, according to The Day, Pete Slosberg of Norwich, Connecticut gave up on his home-brewed wine efforts and moved into more time-efficient beer-making. Seven years later, Slosberg first sold Pete's Wicked Ale to the public — a thick, strong, and flavorful beer and history's first American Brown Ale. The product was very different from American-style lagers like Miller Lite and Budweiser.

After rolling out several more beers, Slosberg sold Pete's to The Gambrinus Company in 1998. Just two years into its ownership, Gambrinus reformulated Pete's Wicked Ale to give it a lighter taste. In 2011, Gambrinus sent a letter to distributors announcing that it would no longer make any form of Pete's Wicked Ale, citing poor sales. This marked the last call for a very influential beer.

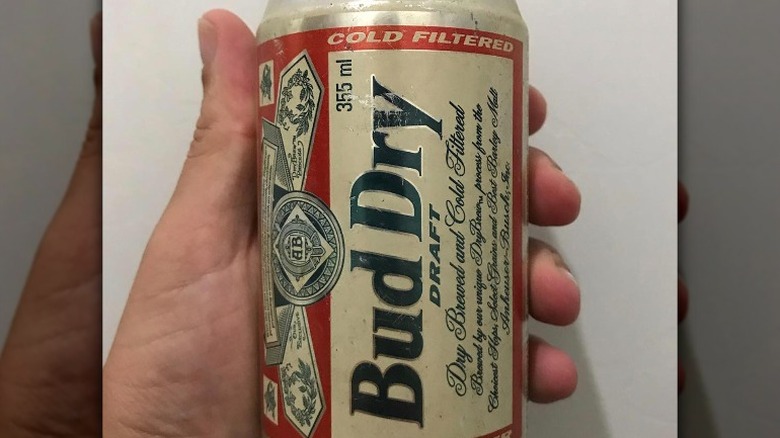

Bud Dry

In Japan in the late 1980s, dry beer was incredibly popular. Brands like Asahi Dry were made in much the same way that so-called dry wines are made. Yeast is used to consume sugars and starches, which are converted into alcohol. Some of those sugars remain and give the beer a slightly sweet flavor, but dry beers utilize so much extra yeast that it eats virtually all of the sugars. This yields a non-sweet beer with almost no aftertaste on the palate. In 1989, American brewing giant Anheuser-Busch unveiled its own version of dry beer with Bud Dry. A brand extension of its Budweiser and Bud Light brands, a serving packed slightly more calories than a Bud Light but maintained the relatively high alcohol content of a Budweiser.

Bud Dry was heavily marketed with a string of Budweiser TV commercials that featured people drinking the product and asking bizarre rhetorical questions, leading up to the slogan, "Why ask Why? Try Bud Dry." The beer sold well for a few years, likely out of curiosity since the ads didn't do much to explain a product that was new and different to most Americans. Sales slowly but dramatically dwindled, though, and Anheuser-Busch started to pull the plug on Bud Dry in 2006. Production officially ended in 2010.

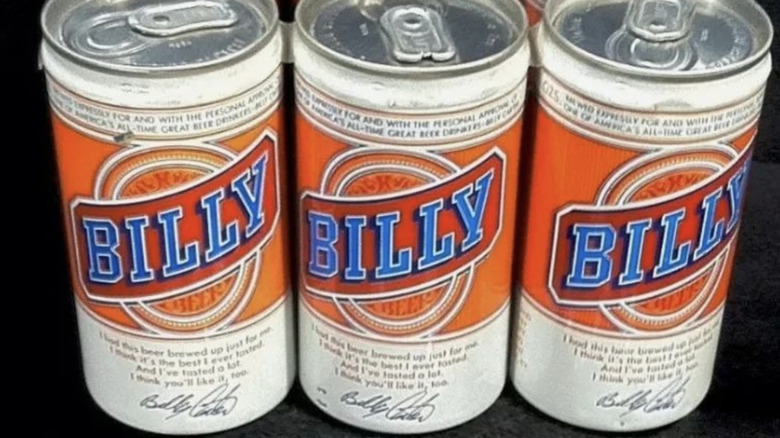

Billy Beer

The breakout character of Jimmy Carter's 1976 presidential campaign was arguably his brother Billy Carter, a gas station owner and self-professed mass-consumer of beer. An affable, regular guy, Billy spent much of his brother's presidency making paid personal appearances to capitalize on his strange "redneck" brand.

Making beer since 1905 but on the verge of collapse in 1977, Louisville, Kentucky company Falls City Brewery set out to save itself with what seemed like a couldn't-miss proposition. It enlisted Billy to lend his name to a new brew called Billy Beer. Per Mental Floss, Carter allegedly received $50,000 for the use of his name and to promote the beer. Cans came adorned with his signature and a quote attributed to him: "I had this beer brewed up just for me. I think it's the best I ever tasted. And I've tasted a lot."

Carter was as detrimental to the product's marketing as he was an asset. At times, he'd get inebriated at public events and declare that he actually wasn't a huge fan of his own beer. A lot of consumers bought Billy Beer out of curiosity, but not nearly enough stayed with it. It didn't save Falls City, which went out of business just a year later in 1978.

Falstaff

Anheuser-Busch emerged as the dominant St. Louis brewer in the mid-20th century. But according to the Riverfront Times, it had some competition before Prohibition thanks to the Lemp Brewery. The company was sold and renamed in the 1920s, becoming the Falstaff Brewing Company — a name that paid homage to the drink-loving Shakespeare character. Its signature beer (when they could legally produce it) was a light, American-style lager.

After alcohol became completely legal again in 1933, Falstaff built itself into a national brand by buying out failed beer companies' facilities in St. Louis and around the U.S. That strategy proved overly complicated and costly, however, and Falstaff steadily lost market share to its more efficiently run crosstown competitor, Anheuser-Busch. The last Falstaff Brewery in St. Louis stopped making beer in 1977, and operations limped along — produced by contracted breweries — until 2005, per St. Louis Magazine.

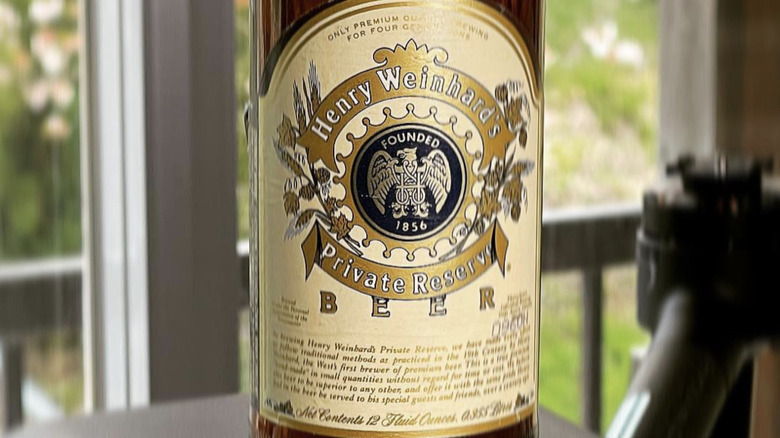

Henry Weinhard's Private Reserve

Portland is generally regarded as one of America's top beer cities. Home to a robust craft brewery community, the city's beer culture is almost as old as the city itself, with Henry Weinhard opening his earliest operations there in 1856 — five years after Portland was founded, according to Oregon Public Broadcasting. In 1976, parent company Blitz-Weinhard started producing its signature offering of Henry Weinhard's Private Reserve, a light-tasting Bavarian-style lager that proved to be a bestselling session beer in and around the Pacific Northwest for many years.

Blitz-Weinhard shut down in 1999 and eventually fell under the corporate umbrella of beverage conglomerate Molson Coors. In August 2021, the company announced that it would stop making a number of beer products as it shifted resources to more elite brews and hard seltzers. Among the lines that the company opted to cease brewing was Henry Weinhard's Private Reserve.

Budweiser B to the E

When popular club drinks like Vodka Red Bull started to dominate nightlife for young partiers in the 2000s, some beer companies were quick to try to cash in. Jealous of the sales that energy drink cocktails got at the expense of more traditional night-out beverages, Anheuser-Busch responded in 2005 with BE, also known as B to the E, a Budweiser-branded beer and energy drink hybrid. The "B" meant "beer" and the "E" meant "extra," with invigorating additions like ginseng, caffeine, and guarana, as well as mixed berry flavors. With an ABV level of 4.5% and 54 milligrams of caffeine, the per-can cost on release was generally even to or even less than that of a lone Red Bull at the time.

The drink was initially popular in America, but Anheuser-Busch's attempts to roll it out internationally flopped. According to The Morning Advertiser, it was gone from British outlets in 2006, presaging its disappearance from American clubs and stores not long after.

Krueger's

It's easy to take the idea of beer in a can for granted. While it's sold in bottles and available on draught in every bar in the country, it may seem like simple, watery, mass-produced beers have always been sold in 12-ounce aluminum cylinders. But somebody had to be first, and the pioneer of packing individual servings of beer in cans was the Gottfried Krueger Brewing Company.

According to Wired, the American Can Company had attempted to can beer as early as 1909, but it took it until 1933 to design a container that didn't explode from the pressure of carbonation. Once it finally had a working model, American Can presented the invention to the nearly century-old Krueger. In 1935, Krueger produced two of its established beers in the cans – Krueger's Cream Ale and Krueger's Finest Beer — and began selling them in Richmond, Virginia. The brewery had a hit on its hands. Within months, Krueger was canning 180,000 beers every day. By the end of 1935, 37 more breweries made the switch to cans.

Making history and innovating couldn't save Krueger, however. By 1961, the company was faltering, which is when beer-maker Narragansett acquired the brewery and began phasing out its products.

Red White & Blue

Red White & Blue arrived on the burgeoning American beer scene in July 1899, created by the Pabst Brewing Company in time for the Independence Day holiday, according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. The patriotic name made sense, but Red White & Blue's biggest selling point was its value. It was a crisp, light lager that was highly drinkable in part because of its low alcohol content — 3.2% — and a six-pack could cost as little as 89 cents in the 1970s. Red White & Blue was so inexpensive that Milwaukee bar The Avalanche used it as the liquid of choice for its "naked beer slide" in the 1980s (per On Milwaukee).

In the decades after, Red White & Blue faded from prominence to where Pabst no longer produced it in any meaningful quantity. In July 2018, the Pabst Milwaukee Brewery and Taproom officially revived the parent company's old brand, holding a beer garden party and adding the product to the pub's taps (per Milwaukee Record). Never mass-produced again in bottles or cans, Red White & Blue died off for good when the taproom closed in 2020.

Hop'n Gator

While it sounds like a clever and evocative name describing an alligator mid-jump, the name of this briefly sold, very unpopular 1960s beer tells the consumer exactly what they're getting. The "Hop" indicates the presence of hops — the herbal, bitter-tasting plant that gives beer its distinctive flavor — and "Gator" is short for Gatorade. Robert Cade, the inventor responsible for Gatorade, also devised Hop'n Gator, first produced and distributed through the Pittsburgh Brewing Company in 1969.

The hybrid beverage was confusingly touted both as a beer (cans called it "lemon-lime lager") and something different (cans also declared it "a new alcoholic beverage"). The most notable thing about Hop'n Gator, other than that it combined two very opposite drinks, was its strength. Pittsburgh Brewing said a serving packed 25% more alcohol than the average beer at the time. Sales weren't great, however, and after a series of business issues and rebranding the drink as a malt beverage, Pittsburgh Brewing stopped making Hop'n Gator in 1975.

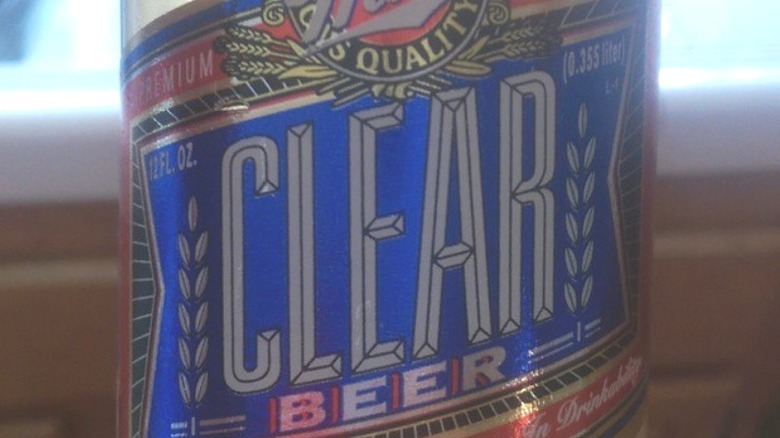

Miller Clear

For a very brief moment in the early 1990s, producers of both alcohol and soft drinks tried to make clear beverages the hottest fad around. According to the Washington Post, corporations aimed to create a mental link for consumers between clarity and purity. Judging by the short popularity of the bottled malt beverage Zima and the brief shelf life of Crystal Pepsi and Tab Clear colas, it never developed into a proper fad or cultural sensation. But in 1993, when it looked like transparent, bubbly beverages could define the decade, Miller Brewing Company unveiled Miller Clear. The beer company claimed that the light beer was a response to market demand for beers with lots of flavor, but which didn't leave drinkers feeling sluggish. With 122 calories per serving, it fell between regular and other light beers.

Miller had a difficult time marketing Miller Clear. Traditionally, the more golden a beer is in color, the more flavorful it's assumed to be. On top of that, the connotations of it being an all-natural product were largely undone by the then-odd process by which Miller made Miller Clear: activated charcoal absorbed the color (and reportedly, a lot of the taste) of the brew. At any rate, Miller Clear slowly faded from the marketplace by the mid-1990s, much like every other clear beverage did.

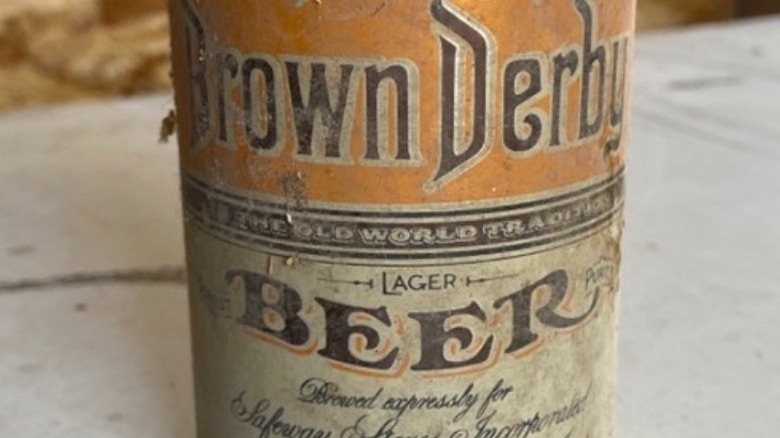

Brown Derby

Canned beer emerged and was met with an immediately enthusiastic public acceptance in 1935. Brown Derby was among the first slate of brands made available in small aluminum cans. Produced by the Humboldt Malt and Brewing Company of Eureka, California, the pilsner-style Brown Derby was made exclusively for the Safeway grocery store chain, with the beer serving as its in-house brand to compete with nationally known beers. The first run of cans bore the image of a derby hat and an umbrella — a design that tread a bit too close to the imagery associated with the well-known Brown Derby restaurant in Los Angeles. According to "Beer: A Genuine Collection of Cans," this striking similarity led to a lawsuit that ended with Humboldt changing the can design to a more original one.

Safeway sold so many cans of Brown Derby beer in the immediate post-Prohibition years that Humboldt Brewing had trouble keeping up. Humboldt eventually shut down, and a series of smaller West Coast brewers stepped in to keep supply up, manufacturing the beer until 1988. Over time, though, the beer was phased out, leading to its entry on the discontinued list.