The Unexpected Health Food Origins Of The Classic Milkshake

While milkshakes could once be found in drugstore soda fountains on every street corner, Tastewise states that they are now listed on only 8.45% of restaurant menus. At least part of this downward trend comes with the evolution of contemporary social culture. In the great economic boom of the 1950s, when cars became accessible to families who formerly couldn't afford them, the concept of the drive-thru made drugstore counters and their specialty beverages a bit less mainstream. Ironically, fast-food drive-thrus are among the few places today where milkshakes are still widely ordered.

With nearly 95% of the population possessing genes for lactose intolerance, there may also be a scientific explanation behind milkshakes' retreat from a dietary staple to an occasional treat. Coupled with a greater awareness of the health detriments associated with a full-fat drink, milkshakes are not the cultural cornerstone they once were. But recent history has proven that there would be an uproar if milkshakes were to vanish off menus completely (like the supply-chain shortages that kept milkshakes from U.K. McDonalds in the summer of 2021).

The milkshakes we know and love today, however, have evolved very far from their humble origins. Once considered the health tonic (and previously made without the addition of ice cream), the original milk shakes were a tasty and convenient form of nutritional supplement that fortified soldiers and arctic explorers in addition to simply keeping hungry populations fed.

Victorian drugstore tonics

The first recorded "milk shake" dates back to the soda fountain craze of the Victorian era, when drugstores began serving beverages on-site as tonics for various maladies (with cream and sweetener added to make the medicine go down). Per Art of Drink, The Atlanta Constitution described how to create this novel beverage in 1886 and how an employee behind the counter "pours out a glass of sweet milk, puts in a big spoonful of crushed ice, puts in a mixture of unknown ingredients, draws a bit of any desired syrup" and then shakes everything in a tin can, topping the frothy milk with nutmeg.

Though foamy, the texture of this Victorian Milk Shake was still distinctly liquid, a step above chocolate milk. But many other flavors were popular at the time, among them pineapple, coffee, strawberry, ginger, banana, and peach — any syrup used for soda was fair game for this mixture too. Bolder customers, however, might have opted for the considerably richer cream shake, incorporating the same ingredients but substituting half the milk for heavy cream (while probably mitigating health benefits with saturated fats).

But if this step up still wasn't enough added cholesterol, there was the option of egg cream, substituting milk for cream and eggs which, once shaken, took on a fairly milkshake-like consistency. One step even further at many drugstores was the option of an adult variant similar to eggnog, emphasizing the ingredients of eggs and (purely medicinal) whiskey.

The health necessity of malted milk

While the milk shake phenomenon reached drugstores across America, an Englishman was adapting his own health tonic that would soon be served in the same places. James Horlick was a chemist who built up a career with a baby formula company before experimenting with his own nutritional powder for adults and children alike. He joined his brother, William, in the States, where they introduced malt powder, a source of digestible sugars marketed to a distinct demographic as "Infant and Invalids Food."

Malt powder was produced by soaking barley grains until they germinated, a process that was also used to make beer and whiskey by leaving the grains to ferment. But by drying the grains to stop the germination process and mixing them with wheat extract in a vacuum, Horlick was able to lock in their nutritional value and create a stabilized powder. Added to milk, it made a wholesome drink that quickly won over health-obsessed Victorians from all walks of life.

But in the 1880s, pasteurization had not yet caught on. The Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences explains that milk was often contaminated with pathogens that spread diseases such as diphtheria, typhoid, scarlet fever, and tuberculosis. To avoid the risks of tainted milk, Horlick devised a way to safely powder milk with malt, forming a convenient all-in-one powder that was added to water. This malted milk was advertised as "Horlick's Food," and became even more popular than its previous iteration.

Horlick's fuels through world wars and Depression

Horlicks also manufactured tablets for even greater convenience. Fortified with vitamins and minerals such as zinc, calcium, vitamin A, and vitamin B6, these tablets became a staple in children's lunch boxes as a portable source of nutrition masquerading in the form of candy. As passable meal replacements, Horlicks Malted Milk Tablets also fueled British expeditions to the tropics, the Himalayas, and the poles, and kept WWI soldiers fortified during long marches on the Western Front. These tablets played an even bigger part in WWII when they were included among the essentials for life-raft rations and aircrew escape kits.

Once poverty became exponentially more widespread in the U.S. during the Depression, Horlicks Malted Milk Tablets were an affordable source of calories and nutrients and remained an emergency pantry staple well into the 1950s. Though initially very popular in the U.S. and U.K., Horlicks tablets had even greater popularity in Commonwealth countries. Regarded as nutrition supplements, they were a convenient source of vitamins in places where much of the population was unable to fulfill daily nutrition needs. Today, despite much greater access to nutritional resources, malt drinks still remain popular in India especially, where they continue to be marketed as health drinks.

Temperance and the ice cream parlor

Horlicks' rise to popularity coincided with a global reform movement to limit or altogether eradicate alcohol. The temperance movement began in the early 1800s, with large moral and religious backing to counter the rise of widespread alcohol abuse. While it began as a scheme to encourage alcohol in moderation, it came to promote abstinence under the guise of Christian virtue, though there was a universality behind the movement that drew many women to the forefront of this cause. These women hoped that preventing alcoholism and promoting abstinence would limit poverty and put a stop to domestic violence.

To inspire the possible success of an alcohol-free society, many non-alcoholic gathering places emerged. Ice cream parlors and soda fountains attempted to replace bars and saloons by providing the same social atmosphere where people could enjoy beverages without the risk of drunkenness. "Soda fountains" refer to the literal machine that dispensed carbonated beverages, but also came to mean the counter surrounding the apparatus, where customers could sit to enjoy a drink. These fountains were often located inside ice cream parlors, though were just as frequently found inside drugstores and pharmacies. In these locations, Horlicks Malted Milk was a natural choice on the menu, as it was a beverage considered as healthful as it was palatable.

The original malt

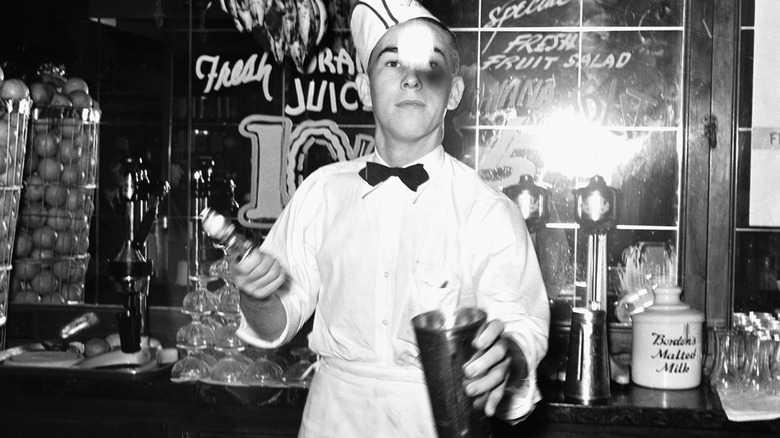

By the 1920s, drugstores and soda fountains were more or less synonymous in the States, as most pharmacies had a soda fountain at their counter. The milkshake as we've come to know it today was first created behind the counter of a Chicago Walgreens soda fountain in 1922. While milk shakes had been popular at such places well before this, and had long since adopted malted milk powder into their hand-shaken recipe, it was one Walgreens employee's revolutionary addition that changed the consistency and popularity of the Milk Shake forever.

Ivar "Pop" Coulson took malted milk one step further by adding two scoops of ice cream to the usual milk, malt, and chocolate. Naturally, this enhancement in taste and texture caught on. At a time when ice cream was more prevalent due to improved refrigeration technologies, Pop's ice cream-enhanced malt shake quickly replaced its malted milk predecessor (along with any nutritional benefits it may have boasted).

Pop's innovative shake was poured into a malted milk glass only ⅔ full so that the drink could be topped with ample whipped cream. Any remaining malt that didn't fit the aesthetic proportions was served alongside the shake in the metal shaker with a straw of its own. Whether the original reason for this extra volume was due to an excess of the mixture or an inadequately sized glass to accommodate the recipe, the novelty of this surplus shake on the side has become a long-standing tradition of the classic milkshake.

Milkshake vs. malt

With the expansion of mixing possibilities that followed the popularity of this new dessert drink, Pop Coulson's original recipe diverged into two categories to accommodate flavor preferences. Pop's creation became known as a malt, and this drink was so well-loved that the neighborhood soda fountains that went on to serve it became known as "malt shops."

The quantifier as a malt is a distinction that is slight but significant. The only difference between a malt and a shake is that the former includes malt milk powder while the latter does not. Malt powder slightly changes a shake's flavor profile, adding a toasty, slightly nutty, and more distinctly milky flavor which pairs decently with vanilla ice cream, but best complements a chocolate shake.

This slightly savory tint does not mix so well with fruitier ice cream flavors, which is perhaps why strawberry malts are not often on diner menus. Though the difference may be slight, the spoonful of malt powder that goes into a malt shake is said to create a slightly thicker consistency. But because malt powder is made from a combination of wheat and barley, the other differentiating factor is that malts are not gluten-free.

Prohibition redefines drinking

When U.S. Prohibition went into effect in 1920, hard liquor was officially off the menu, prompting establishments to sell more "soft drinks" (any non-alcoholic beverages, though especially the carbonated variety). Soda fountains and ice cream parlors became the only legal venues for an afternoon or evening out. To emphasize this shift, Soderlund Drugstore Museum mentions John Somerset's declaration in a 1920 issue of Drug Topics, "The bar is dead, the fountain lives, and soda is king!"

With ice cream on the rise, numerous alcohol manufacturers began to pivot their businesses in order to keep them legally afloat. Many didn't have to shift far, as they already produced malt in order to brew beer. Big-name brewers like Anheuser-Busch simply started selling malt syrup instead of the end product. While some of this was directed at the soda fountain market with its demand for malted milkshakes, it was also available directly from grocery stores, advertised with a wink to customers intending to start their own home brewing.

The Yuengling brewery evolved differently, adapting its technology for refrigeration and pasteurization to begin producing ice cream in vast quantities. This helped contribute to the ice cream craze of the 1920s, though it also became another occasional front for drugstore subversion. Many drugstores, in addition to selling frozen desserts, also still sold some varieties of alcohol for medicinal purposes, a market niche that helped other distilleries survive prohibition. Aspen Colorado's Aspen Crud cocktail infamously snuck bourbon into a mixture of ice cream.

The milk bar

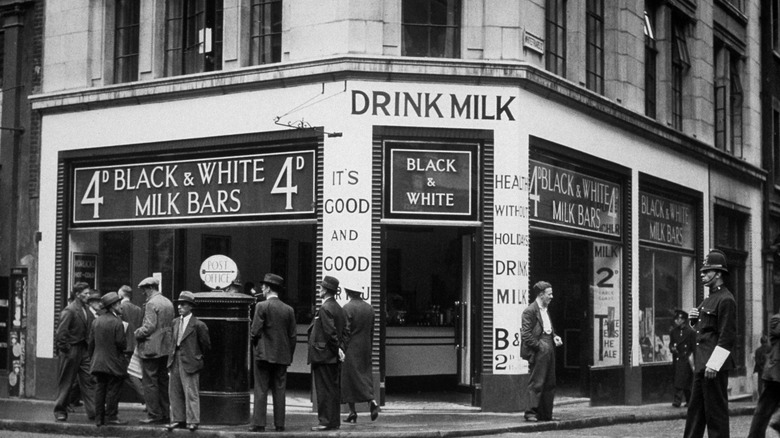

While soda fountains soared in popularity in the U.S. with the turn of the 20th Century, a similar kind of alcohol-free establishment made its way into daily life overseas. The milk bar was a popular venue that had special commonwealth prestige, and the first one, called Black and White 4d, opened for business in Australia, another country that led a strong temperance movement.

Australian milk bars, though they also offered sodas, were the place to go for all manner of milk drinks, particularly milkshakes. In the 1930s, over 4,000 milk bars opened for business Down Under, perhaps gaining esteem due to the National Milk Board's promotion of milk as a healthful drink. Though milk bars, like soda fountains, have long since gone out of style, the few that remain in Australia and other commonwealth countries have evolved into general and convenience stores that still sell dairy products.

Though operating under the same title, milk bars have taken on a different significance in Poland, where they emerged as communal restaurants offering primarily dairy-based dishes. Though somewhat anticapitalist in principle, these milk establishments predate communism in Poland — the first milk bar was established in the 1890s by a dairy farmer who simply wanted to provide nourishing meals that anyone could afford. Serving fast, affordable, wholesome fare, these milk bars became especially popular in the economic aftermath of WWI, and remain a Polish staple today; many are even subsidized by the state.

Technology helped the milkshake evolve

Before the invention of the electric blender, milk shakes had to be shaken by hand and retained a liquid consistency. Enter Hamilton Beach, an originally midwestern manufacturing company founded in 1910 that specialized in motor-driven appliances, made possible after mechanic Chester Beach invented the "universal" motor. Soon this was applied to food mixers, grinders, fans, and sewing machines, among other gadgets, making appliances accessible to households that had formerly only existed on an industrial scale.

Shortly after its inception, the company introduced the Cyclone Hamilton Beach Drink Mixer to the world, which soon appeared on countertops in drugstores across America, lauded for its production of whipped, aerated, and frothy drinks. Mixers made thicker drinks possible, the most extreme being the "concrete," served upside-down for emphasis. The later invention of the bendy straw in the 1930s created the perfect pairing for the milkshake at its zenith, making it easier than ever for anyone to consume before the WWII milk and sugar rations of the following decade necessarily curbed dairy cravings.

Hamilton Beach had its origins in Racine, Wisconsin, a curious coincidence because this was the same area where the Horlick brothers had originally set up business a few decades prior. Racine, on the edge of the Dairy State, is only an hour and a half north of Chicago, where the first malted milkshake was born, suggesting the phenomenon might be the serendipitous success of regional tools, ingredients, and ideas coming together to craft this classic treat.

Protein shakes, the health legacy lives on

While milkshakes briefly regained popularity with the diner culture of the 1950s, a competing type of shake emerged in both mainstream media and consciousness. Protein shakes, which have experienced a renaissance in recent years, first reached widespread appeal in the 1950s in tandem with heightened bodybuilding nutrition, though their proliferation was largely due to more targeted advertising.

Irving Johnson, a supplement salesman, revived a protein mania that had first surfaced in the early 1900s after Plasmon, a German protein powder originally intended for malnourished hospital patients (not unlike Horlick's Food), was marketed outside this demographic to become a sports supplement in Great Britain. After a 1950 article in Iron Man declaring that food supplements were essential to building muscle quickly, Johnson began advertising Irving Johnson's Hi-Protein Food in 1951, which sparked the chain reaction of competing protein powder brands that persists today.

Alongside the protein powder industry came the innovation of shaker bottles, one of many ways to level up a protein shake. Designed as a portable means of mixing and consuming powdered supplements, these bottles harken back to the early days of milk shakes that had to be shaken by hand. With GlobeNewswire predicting the protein supplement market will reach a revenue of more than $32 billion by 2028, this lucrative health-conscious protein shake industry might be closer to what the Horlicks originally had in mind, instead of the ice cream-based trend that became inextricably linked with their malt powder.