The History Of Sushi Is Shrouded In Ancient Legend

Sushi is the quintessentially Japanese dish. So much so that when most people think of Japanese cuisine, sushi is immediately what comes to mind. It may be surprising, then, to learn that the origins of sushi lie outside Japan. The ancient culinary ancestor of sushi most likely came from the banks of the Mekong River in Southeast Asia, originating as a way to keep fish from spoiling in the heat by packing the meat with rice and salt.

In modern times, sushi is a beloved part of Japanese cuisine and culture. Sushi is as much an art as it is a meal, and sushi chefs famously take years of training to master their practice. As such, sushi chefs are greatly respected in Japan for their skills. Each step in sushi making is its own distinct art, and the most important part is knowing how to properly prepare the rice with the perfect combination of texture and seasoning. Just the right combination of vinegar, sugar, and salt gives sushi rice its distinctive flavor, lightly tangy but mild enough to complement the taste of the fish without overpowering it. But modern-day sushi is vastly different from the sushi eaten in ancient times, and rice has not always been such a vital part of the finished dish.

The legend of sushi

As with many of the world's oldest foods, particularly in East Asia, sushi has been eaten long enough to have a legend about its origins. As with all legends, though, there are at least a couple of different versions of the story, but they all revolve around an osprey, a bird of prey specialized in catching fish. In one story, an elderly couple left some rice in an osprey's nest as an offering. When they went back later to check, they found a fish left in the rice, which the bird had seemingly placed there for them as a thank you. When they later ate the fish, they found that the fermented rice had given the fish a distinctive flavor.

In a slightly different version of the story, an old woman was worried that thieves might steal her rice — in days gone by, rice was so important in Japan that it was sometimes used as currency. So to keep her rice safe from thieves, the woman hid pots of it in osprey nests. When she went to recover the rice, though, she found that some of it had started to ferment and also had scraps of fish mixed into it, dropped by the ospreys. Instead of throwing it out, she found that the mixture had stopped the fish from going bad, and tasted surprisingly good.

Sushi's Southeast Asian origins

Despite the legends, sushi seemingly didn't come from Japan at all. The Mekong River in Southeast Asia has historically been a food source for fishing communities who lived on its banks. In the hot, humid climate, however, keeping fish from spoiling was vital for communities, helping to keep a supply of food for times of less abundance. So people developed a way to preserve fish by packing it in salted rice to keep fish from rotting. Since ancient times, cultures around the world have used lacto-fermentation to preserve food, and the cultures of Southeast Asia are no exception. The rice and fish would ferment together, and the added salt prevented any harmful bacteria from causing it to spoil — the same reason why salt is used when making soy sauce.

Some argue that preserving fish this way originated in Southern China, in what is now the southernmost Chinese province of Yunnan. Either way, the method of preserving fish with salted rice likely arrived on the Japanese mainland via Ancient China. In Southeast Asia, though, the flavor of fermented fish is still a common addition to cuisine to this day. One well-known example is nam pla, the fermented fish sauce often used in Thai cuisine. On its own, the scent is overpowering, but a dash of it is a vital ingredient in many Thai curries.

Sushi's long lost cousins

While sushi in Japan evolved into the dish we know today, fermented fish similar to ancient sushi is still found in Southeast Asian cuisines. There's a good chance that foods like these share the same origin. One example is burong isda, a fish and rice dish eaten in the Philippines. It's made by combining fish fillets with cooked rice mixed with salt and angkak, a bright red rice fermented with yeast. The angkak acts as a fermentation starter, and the mixture is left for a week until it's ready. Once it's fully fermented, the burong isda is usually sautéed and served with boiled vegetables, like eggplants, string beans, or bitter gourd.

A similar process is used to ferment fish in Thailand, where the fish are often used to make a condiment called pla ra. An almost offensively pungent cooking ingredient, pla ra is made with fresh river fish fermented with rice bran for at least six months. While the strong aroma may make outsiders hesitant, pla ra is a common ingredient in Isan cuisine from Northeast Thailand, where it's reputedly been used for over 6,000 years. It can also be seen, and smelled, in the marketplaces and kitchens of neighboring countries like Laos and Vietnam.

Narezushi

The original Japanese sushi consisted of a similar kind of fermented fish. Known as narezushi, there are places in Japan where it's still made today. The fish is gutted and then preserved in salt for a few months before being packed in rice and left to ferment slowly. While it's usually fermented for a few months, it can keep this way for decades. Most notably though, the rice isn't eaten as part of the dish. It's too salty and unpleasant. With narezushi, the fish itself takes center stage, either served whole or sliced. The scent and taste are quite strong, with some people comparing it to things like sharp blue cheese. To the modern palate, narezushi is perhaps something of an acquired taste.

When exactly narezushi first arrived in Japan, however, is debated. Some sources say it was first made during Japan's Yayoi period, between 300 B.C.E. and 300 C.E. The Japanese bronze age. The Yayoi Period was when the ancient Japanese first started cultivating rice. Around the same time, this rice was already being used to brew the earliest Japanese rice wine in a process that would later develop into the famous sake (properly called nihonshu) which Japan is now known for. Other sources, however, suggest that sushi arrived from the Chinese mainland a few centuries later, sometime around the 8th century C.E. Whatever the origins of narezushi though, there would still be a long way to go before anything resembling modern sushi would be prepared.

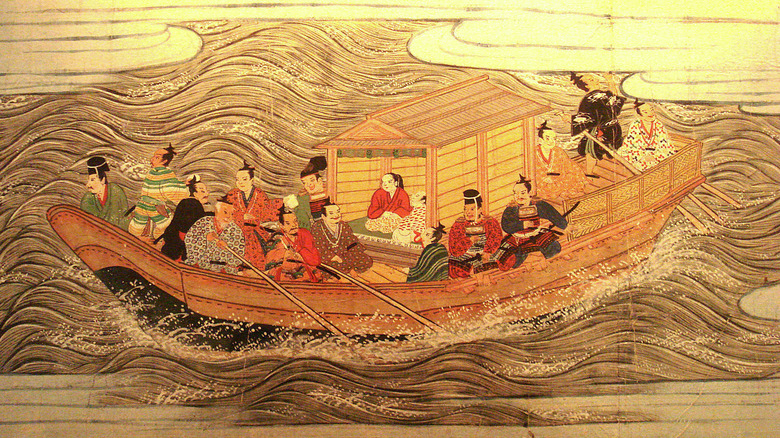

The milder sushi of the Muromachi Period

During Japan's Muromachi Period, in the 14th to 16th centuries, people started reducing the fermentation time for narezushi. Whether this was the result of experimentation of whether someone was simply too impatient or hungry to wait for the full time, people began to prefer the gentler flavor of less heavily fermented fish. The newer version of the dish was called namanare-zushi, which loosely means "raw" narezushi. Usually called namanare for short, this newer kind of fermented fish was much less pungent than the older style narezushi, which may also have helped to make it more popular.

Namanare was ready to eat after only 10 days. As well as being ready to eat much sooner, the shorter fermentation time meant that the rice grains hadn't fallen apart yet by the time the dish could be served. The result was that around this time, sushi evolved into a fish and rice dish, with the fish and tangy fermented rice eaten together. The tangy taste of the fermented rice, similar to the flavor of Japanese pickles (tsukemono) became an essential part of sushi, which later chefs would use vinegar to recreate.

The Edo Period's sushi explosion

Around the 17th century, during Japan's Edo Period, sushi began to develop into something more like what we'd recognize today. Around that time, rice vinegar became a popular cooking ingredient, and chefs began to use it to make sushi. Vinegar gave freshly steamed rice the familiar tang of lacto-fermentation with a dramatically faster preparation time. Fermented fish began to be replaced by fresh fish in a new invention called haya-zushi, literally meaning "fast sushi."

With sushi now quicker to make, it became more accessible than ever before, and chefs began to experiment with brand-new styles and forms. Several of these types of sushi, invented during the Edo Period, are still served in restaurants across Japan today, although not all are easy to find. One type of Edo-era sushi is kakinoha-zushi, consisting of blocks of pressed sushi carefully wrapped in folded persimmon leaves. This dish is quite rare, and it's easiest to find in the traditionally styled restaurants of Japan's historic Nara Prefecture, where it's considered a local specialty. Others can often be found in nearly any modern convenience store, like inarizushi, with blocks of sushi rice stuffed inside fried, seasoned tofu skins. Being so easily available, inari-zushi is a popular choice for picnics in the Springtime, during cherry blossom season. Most significantly though, the Edo Period saw the invention of two defining modern-day favorites: maki-zushi and nigiri-zushi.

Nigiri-zushi

Nigiri-zushi is by far the most common variety of sushi you'll encounter in modern Japan. These are the bite-sized blocks of seasoned rice topped with slices of fish or other things like tamagoyaki, a thinly sliced omelet. In the kaitenzushi (conveyor belt) restaurants in cities like Tokyo and Osaka, nigiri-zushi can be found on most of the plates, made with a variety of different fish. Some specialty restaurants even serve niku-zushi, with the fish replaced by thin slices of seared rare steak.

Nigiri-zushi were invented in the early 1800s in Edo, now known as Tokyo. Their original name was Edomai-zush, with Edomai meaning "in front of Edo," probably because the fish first used to make them was caught in what is now Tokyo Bay. The fish at the time, however, wasn't yet served raw. Without modern refrigerators, it was preserved with soy sauce and vinegar.

The invention of nigiri-zushi is popularly attributed to a chef named Hanaya Yohei. Sushi had previously been made with a press, in a slightly cumbersome process, and Yohei aimed to create an easier dish with a better texture. Yohei's nigiri-zushi, by contrast, was quick and easy to make by hand. Combined with the fresh flavor of haya-zushi, the quick preparation made Yohei's sushi very popular. It became the foundation for the kind of sushi bars that are found on the streets of Tokyo today, where chefs artfully prepare food to order, right in front of waiting customers.

Maki-zushi

The Edo Period saw another important innovation in Japanese cuisine: nori sheets. Made in a similar way to Japanese washi paper, these are the familiar flat sheets of dark seaweed used in a variety of Japanese cooking. Crumbled or flaked nori are popular toppings for Japanese dishes or as ingredients in seasonings like furikake. But nori is most famous by far as the outer skin of maki-zushi rolls, which were invented around the same time as nori itself. Large sheets of nori, usually lightly toasted, could be used to wrap around a filling of rice and fish, and then sliced into the iconic sushi rolls we all know and love.

Invented sometime during the 18th century in Edo, maki-zushi rapidly became popular across Japan, spreading to other cities which each developed their own characteristic styles. The narrow hosomaki, containing only one ingredient wrapped in rice and nori, was originally most popular around the city of Edo itself. In Osaka and the surrounding Kansai region, on the other hand, the most popular maki-zushi were originally the larger futomaki rolls, filled with several different ingredients. Futomaki would later become one of the most popular types of sushi outside Japan, where they would inspire bold new sushi creations.

California sushi

Today, California-style sushi is one of the world's best-known varieties of the Japanese classic. Sushi arrived in California in the mid-20th century, where it quickly became distinct from Japanese sushi. Ingredients like avocado and crab became more common additions, first included in sushi because they were more readily accepted by American tastes than slices of raw fish.

Another notable thing about California-style sushi is that it tends to be much more elaborate. Where modern Japanese sushi usually has a simple and minimalist aesthetic, California sushi is often bombastic and artfully presented. It also has much more emphasis on maki-zushi rolls. Americans may be surprised when visiting Japan, to realize that maki-style rolls are somewhat downplayed there. A meal at a sushi restaurant is typically mostly nigiri-zushi, and it's common etiquette in some Japanese sushi restaurants to order a single plate of maki-zushi at the end of a meal, letting the chef know that the diners are nearly finished with their meal.

By contrast, colorful sushi rolls are often the focus of Western sushi styles. This trend was kicked off by California rolls, also called uramaki. These were invented in the 1960s by a chef named Ichiro Mashita, and they're often coated with sesame seeds or fish roe. These innovations in California's distinctive style of sushi later led to even more elaborate maki-zushi, like rainbow rolls and Philadelphia rolls. They sometimes also have distinctive fillings like tempura, fusing styles of Japanese cuisine which don't traditionally mix.

The ancient flavour of funa-zushi

Sushi has developed and evolved over the centuries, with new regions adding their own distinct twists and ingredients. For the traditionalists though, there are still places that serve the original style of sushi first eaten in Ancient Japan. One good way to find out what this ancient sushi was like, is to travel to Lake Biwa near Kyoto. There, one family makes a dish called funa-zushi, made from a kind of carp called funa in Japanese. Funa-zushi is made to a recipe dating back to 1619 in a tradition going back 18 generations. Just like the original narezushi, it's fermented slowly in rice and salt, and aged for three years before being served. When it reaches the table, it's served as slices of preserved whole fish, just as it would have been in days long gone. The fermented flavor is strong but pleasant, compared to things like blue cheese, and it's as unfamiliar to most Japanese people as it is to visitors from the rest of the world.

Tucked away here and there, traces of sushi's ancient heritage can also be found in other parts of Japan too. Another variety is called izushi. Fermented and pressed, this is a traditional dish on Japan's north island of Hokkaido. While sushi may continue to evolve and develop, both within Japan and elsewhere, it's likely that there will always be people preserving the ancient origins of sushi.