The Complete History Of The Ice Cream Cone

According to the International Dairy Foods Association (IDFA), the global ice cream industry will reach nearly $98 billion by 2027. The United States (in 2021) produced more than 1.3 billion gallons of ice cream. Americans can't get enough ice cream flavors like vanilla, chocolate chip, and cherry.

You can't talk about the widespread popularity and consumption of this frozen treat throughout the years without mentioning the ice cream cone. Ice cream cones (for some people) are an essential accompaniment to ice cream because of the way the light, crispy flavor complements their favorite dairy treat.

To understand the widespread popularity of the ice cream cone, you have to take a look at its history. Like many inventions, the story of the ice cream cone is a combination of happenstance, right place and time, and filling a simple need with a solution that makes all the sense in the world. Knowing the complete history of the ice cream cone will give you a greater appreciation the next time you crunch into one!

Pre-history of the ice cream cone

Like most inventions, there were several precursors that eventually led to the creation of the ice cream cone. The earliest possible visual reference to an ice cream cone precursor is from an 1807 painting. The painting showed a woman seemingly enjoying an ice cream cone that she ate with a scoop-like utensil.

If you lived in England in the 1800s, you probably were eating your ice cream from a short stemmed glass called a "penny lick". As the name suggests, vendors sold ice cream in these glass scoops for a penny. Unfortunately, people of the time also weren't as health savvy as we are now, and would often share and reuse their penny licks. After an 1879 cholera outbreak and impending tuberculosis fears, the medical community blamed penny licks, and they were banned in London before the turn of the 20th century.

An 1888 cookbook made mention of "cornets with cream", which was a recipe for an edible cone that people could use to enjoy their ice cream. The recipe is credited to Agnes Marshall. Marshall's recipe is cited as the earliest reference to the closest version of the ice cream cone that we eat today. Marshall's cones, made with flour and blanched almonds, were used to hold any sort of cream or frozen treat. These historical precursors make it more likely that people commonly used some semblance of the ice cream cone long before it was perfected, mass-produced, and marketed to the public.

The most noted ice cream cone patents

Antonio Valvona, an Italian man living in England, filed a patent in 1901 for a device that baked "biscuit cups" that people could use to serve ice cream. He teamed with Italian-American immigrant Frank Marchiony in 1902 to form the Valvona-Marchiony Company. Valvona stayed behind and ran the factory in England — Marchiony set up shop in the United States.

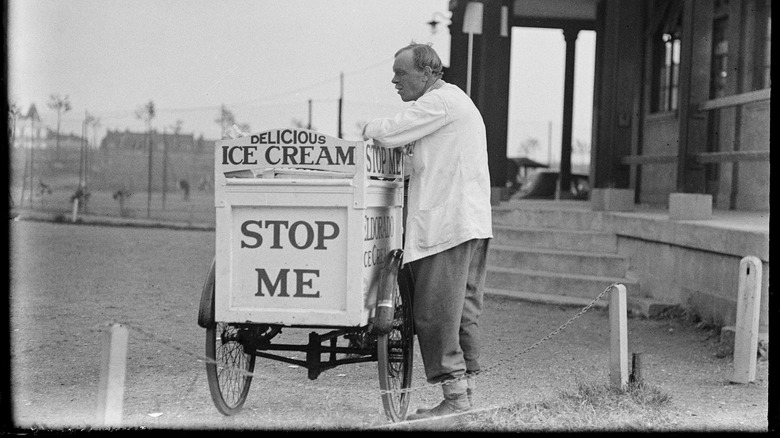

In 1903, Marchiony's cousin, Italo Marchiony, was awarded a patent for a machine for mass producing edible ice cream cups. Italo Marchiony worked as a pushcart vendor in the Manhattan area of New York City selling flavored ices and other frozen treats to customers. He originally sold his treats in liquor glasses similar to penny licks, but his glasses would constantly get broken or go missing.

The idea for the patent came about shortly before 1900, when Italo Marchiony sought an edible solution to his container problem. Marchiony took to his kitchen night in and night out working on a baked waffle that could hold his frozen treats. Folding the waffle into an edible cup fresh off the iron allowed it to hold its shape and support the frozen treats. These waffle cups were a hit with customers, and Marchiony knew he could take the business to another level. Marchiony's cups quickly made him the most popular vendor on Wall Street, and he soon grew his operation to 45 carts. Italo Marchiony is popularly named as the inventor of the ice cream cone.

The St. Louis World's Fair

The 1904 St. Louis World's Fair served as the epicenter of the ice cream cone. It took place on April 30th, 1904 and lasted until December 1 of the same year. The fair brought in roughly 20 million people total, and averaged about 100,000 people daily. This set the stage for a massive debut for the ice cream cone.

Since the ice cream cone already existed, it's more accurate to say that it was popularized at the fair. This is thanks to Syrian Ernest A. Hamwi, who was selling waffle desserts at the fair. Hamwi was baking his pastries right beside another vendor who was selling ice cream scoops. As legend has it, the vendor beside Hamwi ran out of ice cream containers. Seeing the vendor's dilemma and seizing a potential business opportunity, Hamwi started rolling his waffle pastries into cones to serve the ice cream. It was a hit at the fair, and the rest, as they say, is history.

The cone shape is an important distinction that made Hamwi's version different from the baked cups that Marchiony patented. These ice cream cones, called "cornucopias" at the time, exploded in popularity so much that they quickly became the go-to treat at resorts, fairs, and amusement parks all over the country. The Roanoke Evening News, a newspaper several states away in Virginia, called Hamwi's cornucopias "the best money-maker for fairs and public gatherings yet devised" a mere year after the St. Louis World's Fair.

Abe Doumar's ice cream cone claim

With various historical claims, it's important to note others who have been credited with the invention of the ice cream cone. One of the most credible and noteworthy claims is from Abe Doumar, a Syrian immigrant who was a traveling salesman in 1904 at the time of the St. Louis World's Fair. Doumar was in attendance at the fair selling paperweights and other items. His story is nearly identical to Hamwi's.

Doumar says he noticed that an ice cream vendor had closed up shop because it no longer had paper dishes to distribute its ice cream. Seeing this, Doumar bought a waffle and rolled it into a "Syrian Ice Cream Sandwich" so that the vendor could keep selling. He got the idea after seeing another vendor selling waffle pastries topped with whipped cream. Doumar's nephew, Albert Doumar, says that his uncle's inspiration was also rooted in a tradition from their homeland of stuffing pitas with jam and similar treats. In his family's recorded history, Albert Doumar states that his uncle gave Hamwi the idea, and that he could grow his profits by selling cones for 10 cents rather than a penny.

Other historical references support that the young Syrian men knew each other, and the Doumar family donated two ice cream mandrels to the Smithsonian Institute. Abe Doumar's original cone machine remains in use at Doumar's Cones and Barbecue in Norfolk, Virginia. Albert Doumar ran the business for 68 years before his passing.

The Missouri Cone Company

Following the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair, Ernest Hamwi and others in St. Louis began dusting off their waffle irons and going into the ice cream cone business in earnest. New equipment was created to keep up with demand, which grew increasingly as customers got word about the St. Louis cornucopias. Stephen Sullivan of nearby Sullivan, Missouri was one of Hamwi's earliest customers, and would shortly after go down in history as one of the ice cream cone business' first independent entrepreneurs.

Both Hamwi and Sullivan dedicated themselves to their newfound ice cream cone businesses. Sullivan sold his cones at the city of Sullivan's Modern Woodmen of America Frisco Log Rolling, while Hamwi founded and operated his own business: The Cornucopia Waffle Company. Hamwi then opened the Missouri Cone Company in 1910, which would later become the Western Cone Company.

Just roughly 60 miles apart, these ice cream cone forefathers' hard work led to the types of ice cream cones we still enjoy today. These include the original waffle cone, which is rolled, baked, hardened, and served fresh off the griddle, and another type of cone that is baked by pouring batter into a mold.

Frederick Bruckman's machine

Frederick Bruckman's contributions to the ice cream cone industry can't be overstated. After graduating college, Bruckman worked at several creameries before landing at the Weatherly Creamery Company. At this point, vendors and manufacturers were still largely rolling their cones by hand or using cruder forms of machinery. In his travels and after finding inspiration from the post-St. Louis World's Fair buzz, Bruckman brainstormed an idea for a sugar ice cream cone that was sturdy, fit for transport, and that wouldn't stick to machinery. Just as importantly, Bruckman wanted these cones to be affordable for everyone.

After a few years of trial, error, and inspiration, Bruckman finally filed a patent in 1912 for a machine that could roll ice cream cones. It was fortunate timing, as it immediately came after a heat wave, which means that customers were primed and ready for cold treats. In just a few short years, Bruckman's cones were already producing 1 billion cones in a single year — an unfathomable achievement for the time. The sugar cone's popularity skyrocketed, allowing Bruckman to comfortably retire from his thriving business in 1919.

Bruckman's invention made it possible for companies to sell ice cream cones en mass in storefronts, grocery stores, and other such establishments. He would later go on to sell the company and all its patents to Nabisco, which would take the invention's reach to even greater heights. You might recognize this product today in the form of Nabisco's Comet sugar ice cream cone.

Valvona-Marchiony lawsuits

An invention story isn't complete without a lawsuit. With the ice cream cone market now in full swing after the St. Louis World's Fair, Antonio Valvona's 1901 patent became a valuable asset, which the Valvona-Marchiony Company used quite frequently. The company sued several competitors for copyright infringement, including one named D'Adamo in 1905.

This proved to be a victory for the Valvona-Marchiony Company, as a United States Circuit Court judge ruled that D'Adamo's ice cream mold was virtually identical to Valvona's. As a result, D'Adamo was forced to cease and desist. The result of the D'Adamo case set the tone for several other lawsuits filed by the Valvona-Marchiony Company. Even Frank Marchiony's cousin, Italo Marchiony wasn't safe.

The Valvona-Marchiony Company sued Italo Marchiony in 1913 in the United States District Court of New Jersey and won. The business partners again used Valvona's 1901 patent as the basis for their complaint. The courts not only agreed, but said that Italo Marchiony previously admitted to infringing upon the idea while working in his cousin's business, and made minor mechanical changes to avoid infringement.

The case ruled in detail that Italo Marchiony invented no part of the patented device. It further stated that Italo worked with the Valvona-Marchiony Company, learned all he wanted to learn, dissolved the partnership, and went into business for himself using his 1903 patent. Both the D'Adamo and Marchiony cases were used as precedent in suing several other companies and individuals for infringement as the business boomed.

Appeal to Valvona-Marchiony's lawsuit

The Valvona-Marchiony patent reached the federal appeals court level for the first time in 1914. This came after the company lost the Valvona-Marchiony Co. v. Perella copyright infringement case the prior year. In the Perella case, the courts ruled that the most distinguishing characteristic of the Valvona patent was in the heating element. Language in the patent states that the heating element absorbs and conducts "sides of the mold being of substantially the same thickness."

The appeals court judge ruled that Perella's device does not conduct heat in the same way, is heavier, and does not require uniformity in thickness. With the burden of proof being on Valvona-Marchiony, the complaint failed, which led to the 1914 appeal.

This United States Court of Appeals case was a significant loss for the Valvona-Marchiony company, and an even more significant victory for ice cream cone makers everywhere. The case not only upheld the Perella decision, but went further to render the Valvona patent void.

An appeals court judge noted the wild popularity of ice cream cones, which a patent would monopolize. The judge ruled that Valvona's patent never stated that his baking cups were for ice cream, that the shape was a cup and not a cone, that the use of baking dies is as old as the waffle itself, and that the original patent was mechanical in nature, not inventive. This ruling officially made the production of ice cream cones open to everyone, without fear of infringement.

The ice cream cone business booms

The story can't be complete without the birth of the company that would go on to become the world's largest ice cream cone manufacturer. In 1918, the George and Thomas Cone Co. was founded by two Lebanese immigrants, Thomas J. Thomas and Albert George. The two men started the company selling baked goods and quickly started producing ice cream cones. The business began in Hermitage, Pennsylvania with a single hand-operated ice cream cone oven, selling cones to customers in Brookfield township. Thomas would exit the company shortly after its founding, leaving George to run it.

As mass production surged in the roaring 1920s, so did the ice cream cone business. Ice cream cone production hit a milestone of 245 million in 1924, per the International Dairy Foods Association (IDFA). Another significant development for the modern production of ice cream cones happened in 1928. This was the year that J.T. "Stubby" Parker of Fort Worth, Texas invented a cone that could be kept in the freezer alongside ice cream. In 1931, Parker solidified this invention by forming the Drumstick Company.

Not only did this lead to an entirely new genre of frozen desserts, but Parker's cone also helped the manufacturing process by allowing cones to be shipped further without spoiling. These advancements set the stage for production that has allowed the ice cream cone business to become what it is today.

Flavor and feature upgrades

Once the foundation was laid, well, the rest is history. Mass produced frozen treats from Stubby Parker's Drumstick Company have become timeless classics. It's not summertime until you see people pulling Nestle vanilla, chocolate, and triple chocolate drumsticks out of the freezer. Having long bought Frederick Bruckman's company, Nabisco is offering its own infusions, including Oreo cookie ice cream cones.

Ice cream cones today come in a wide variety of flavors, including chocolate, vanilla, peanut butter, and chocolate chip. These choices pair well with ice cream flavors of all types, and are enjoyed at home and in ice cream establishments all over. The waffle cone is still a favorite for many, but people today also enjoy cake cones, matcha green tea cones, and other interesting cones. Ice cream giant Häagen-Dazs is hoping to further ice cream cone history with its butter cookie cone. The butter cookie cones have chocolate on the inside and are paired with the brand's ice cream flavors, such as chocolate, vanilla, and strawberry.

Foodies have also gone crazy with innovation, creating ice cream cone choices like the bacon waffle cone, cinnamon roll cone, Fruity Pebbles cone, and Graham Cracker cones. Companies are even leaning into the wellness industry, offering ice cream cones infused with CBD, protein, fiber, and probiotics. With today's manufacturing technology and several players in a thriving ice cream industry, you can expect to see continuous innovation.

The legacy continues

The most important part of any history is the ability to preserve and continue it. The history of the ice cream cone is as much a cultural phenomenon as anything else. Its impact remains, as Missouri in 2008 named the ice cream cone the official dessert of the state. This solidified the officially recognized birthplace of the ice cream cone more than 100 years after the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904. Stubby Parker's drumstick remains the ice cream truck item of choice in several states.

The George and Thomas Cone Company, now known as the Joy Baking Group, celebrated its 100-year anniversary in 2018. The current CEO, David George, is the grandson of the original founder. Today, the company manufactures more than 40% of the cones that stores in the United States sell. The Joy Baking Group also manufactures more than 60% of the ice cream cones sold in ice cream shops and restaurants. In 2021, the company announced a 3,000 square foot expansion of its ice cream cone plant.

Of course, our appetite for ice cream cones hasn't slowed down either. The average person in the U.S. eats about 4 gallons of ice cream annually, according to the International Daily Foods Association (IDFA). People enjoy eating their ice cream in a cone so much that September 22 has been designated National Ice Cream Cone Day. The legacy continues, as today, you'll find ice cream cones served at any fair or amusement park around the world.