Here's What The P65 Warning Label Means For The Safety Of Your Food

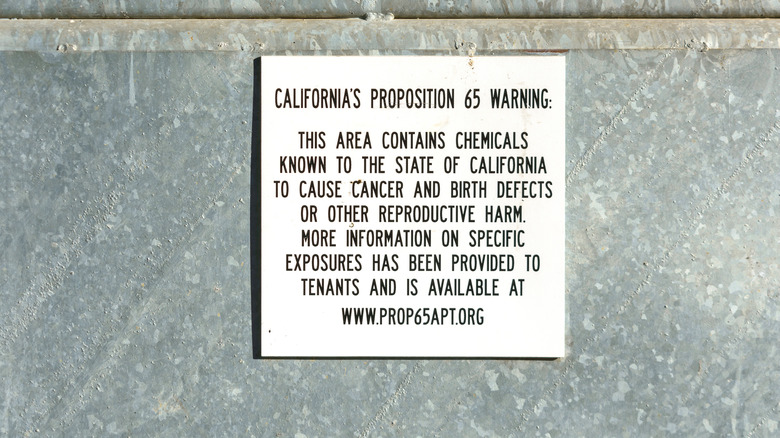

You've probably seen one by now: a warning label with a bold black exclamation point surrounded by a bright yellow triangle. It's the same color scheme as caution tape, and it's meant to deliver the same fundamental message: beware. You can find these labels on seemingly any product from foods and beverages to soaps, cosmetics, cat litter, and household appliances, and they all say some variation of the same thing: "WARNING: This product can expose you to chemicals known to the State of California to cause cancer, birth defects, or other reproductive harm. For more information, go to www.P65Warnings.ca.gov."

It's alarming, to say the least, not to mention perplexing for the many people outside California who have recently encountered such warnings when shopping online. The only words more alarming than "cancer" are "birth defects" and "reproductive harm," so it's clear we have a high-stakes situation on our hands.

Non-Californians encountering these labels for the first time probably don't know the backstory behind them, and honestly, neither do many California residents, but the key lies in that mysterious term "P65." It refers to Proposition 65, a California law that dates back to 1986. Despite being on the books for so many years, Proposition 65 seems to be creating more buzz today than ever before. If you think you've been seeing more warnings than usual over the past decade, you're absolutely right. There are a few reasons behind this and a great deal of controversy, so let's break it down right now.

Prop 65 was intended to reduce water pollution

The story of Proposition 65 begins in the late 1900s when Californians experienced a series of scares over contaminated tap water (a danger that still persists). In 1984 a bombshell report revealed that solvents used in the burgeoning Silicon Valley tech industry had leaked into the groundwater. According to Vox, In the wake of this revelation, a group of climate activists led by prominent members of the entertainment industry, including Jane Fonda, Whoopi Goldberg, Chevy Chase, Shelley Duvall, Rob Lowe, Ed Begley Jr., and Cher, began campaigning for a new law: the Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act, better known as Proposition 65.

There was more to the story on the political front. California was holding a gubernatorial election in 1986, with Republican incumbent George Deukmejian being challenged by Tom Bradley, the Democratic mayor of Los Angeles. Bradley's campaign put a spotlight on pollution, an issue Deukmejian had a poor track record of, and political strategist Tom Hayden conceived of Prop 65 as a way to draw more voters to the polls in the name of cleaning up the water supply, according to the Los Angeles Times. Hayden was married to Jane Fonda, and the power of celebrity endorsements gave the bill a huge boost. It was primarily written by environmental attorney David Roe, and was ultimately approved by voters with an impressive 2-1 margin. However, Bradley lost the gubernatorial race, and it soon became apparent that Prop 65 wasn't going to be as straightforward in practice as it had been in theory.

Prop 65 has faced growing criticism since its passage

Proposition 65 was supposed to persuade companies to stop using carcinogenic chemicals in their products, and in its early years, it seemed to do just that, leading to upgrades in faucets, water filters, and hair dyes among other successes. Major companies were forced to pay millions of dollars to settle lawsuits brought by consumers, but in the years since, suspicions have fallen upon lawyers who charge massive attorney's fees in such suits while their cases become less and less persuasive, per Vox. The list of chemicals covered by Prop 65 has now exceeded 900, but the actual threat they pose has been called into question since many of them were only labeled dangerous after massive quantities far exceeding those of any consumer product were force-fed to lab rats.

The biggest problems arose when companies began slapping P65 labels on products without even testing them, just to guard against potential lawsuits. At that point, the labels weren't communicating anything useful, so in 2018, California updated the law. Now, P65 labels must name at least one specific chemical from the list that has been identified in the product in question, meaning companies actually have to test their goods. The revised text also set new standards for labeling e-commerce products, which is why you might have seen P65 labels even when you don't live in California. They now show up on most major online retailers, including Amazon, and you may be seeing even more in the future.

Why you'll find Prop 65 labels on food

According to the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, there are several chemicals that consumers should be warned about. Alcohol is one, as drinking while pregnant can cause birth defects. Plus, alcohol has been linked to multiple forms of cancer including liver, colon, and rectal cancer. Another danger lurking in your food is mercury, often found in high levels in certain fish. Mercury has been linked to kidney disease and has caused tumors in lab rats. The amount of mercury in seafood is generally low enough that you shouldn't worry, but certain fish such as swordfish and marlin have higher levels.

Acrylamide is a naturally occurring chemical that has been linked to cancer in lab rats. According to the FDA, it forms when foods are cooked at high temperatures and is most commonly found in processed plant-based foods including cereals, crackers, fries, and potato chips.

Bisphenol A (BPA) is sometimes in the lining of cans and jar lids. BPA has been linked to cancer, but fortunately, its industrial use has greatly decreased in recent years. Nevertheless, it remains a common target of P65 warnings.

It is important to note that the studies linking these chemicals to cancer don't necessarily reflect the real risk. The MD Anderson Cancer Center notes that such research typically entails exposing lab rats to massive amounts of the compound, like the tests linking acrylamide to cancer, in which rats were given 1,000 to 100,000 times more acrylamide than you'd find in any food.