What Is Mutton And How Should You Cook It?

Lamb has been a staple of the diets of humankind for thousands of years. According to the Center for the Advancement of Foodservice Education, there is evidence for the domestication of sheep in regions spanning the Mediterranean and Central Asia as far back as 9000 B.C. These early civilizations valued sheep for more than just their meat. Every part of the animal, from head to hoof, was utilized for fuel, clothing, and even art.

One need not look further than religion and literature for examples of the centrality of sheepherding to human civilization. Several of the most notable figures, from Jesus to Muhammad, were shepherds. And cultures across the globe have long observed rituals of lamb sacrifice and consumption surrounding religious holidays of all kinds.

According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, sheep and goats are the fourth most commonly consumed meats globally. While The Science Agriculture notes that China is the top sheep-producing country in the world, the highest per capita sheep consumption, which includes lamb and mutton, is in Kazakhstan, at 8.7 kilograms annually, per OECD data.

While sheep encompasses animals of all ages, there is a big difference between lamb and mutton. Most Americans are familiar with spring lamb, which can be as juicy and tender as beef. Few are accustomed to the idea of consuming older sheep, like mutton. Let's look at what mutton is, what it tastes like, how to cook it, and where you can find it.

What is mutton?

At its most basic, mutton defines mature sheep. The term describes sheep of both sexes, both ewes and castrated wethers. This term is also commonly used to refer to mature goats in some East Asian and Caribbean cultures, somewhat muddying the waters. For our discussion, we use it to describe the meat derived exclusively from sheep.

The etymology of the word itself stems from the Proto-Celtic word for a ram, "moltos," which evolved to "mutton" in Gaulish, "moltō" in Latin, and "mouton" in French. It is generally accepted that mutton refers to sheep that are at least two years old when slaughtered.

This can be further differentiated, though these distinctions may vary by country, farm, and even breed of sheep. Hogget, or yearling, typically bridges the gap between lamb and mutton, referring to sheep between one and two years old at the time of slaughter. Spring versus autumn lamb divides those animals slaughtered before and after six months of age. Finally, milk-fed lamb, considered a delicacy in countries across the Mediterranean and Asia, refers to animals four to six weeks old at slaughter.

Mutton vs lamb

Differences between mutton and lamb go far beyond age. They include texture, size, color, smell, taste, and cost. Lamb is a delicate meat that remains moist and tender when cooked. This is because it hasn't had the time to develop muscle, fat, or connective tissue. It also should go without saying that lamb is smaller than the equivalent meat from mutton.

From a visual perspective, lamb tends to be a brighter, almost pinkish hue. Mutton is often a darker, purplish-red color. The aroma of lamb is also distinct from that of mutton. Lamb has a very mild scent that is sometimes described as being almost sweet. Mutton has an aggressively gamey nose, particularly those animals also used for wool. Where taste is concerned, lamb is mild, grassy, and even sweet when cooked. This is not the case with mutton, which can be gamey and strong, especially when prepared by inexperienced hands.

From a cost perspective, mutton is markedly more affordable than lamb. Sheep are a valuable commodity. Many cultures revere these animals for their utility in numerous capacities. They would never dream of slaughtering an animal before it has fully matured. To do so would be wasteful. Even once processed, not a morsel of the meat from a sheep is wasted.

In Morocco, for example, it is not uncommon to find sheep heads and brains cooked in a delectable peppery broth. This is considered a delicacy and something to be savored. In the U.S., we seldom see anything but the prime cuts of meat on a menu.

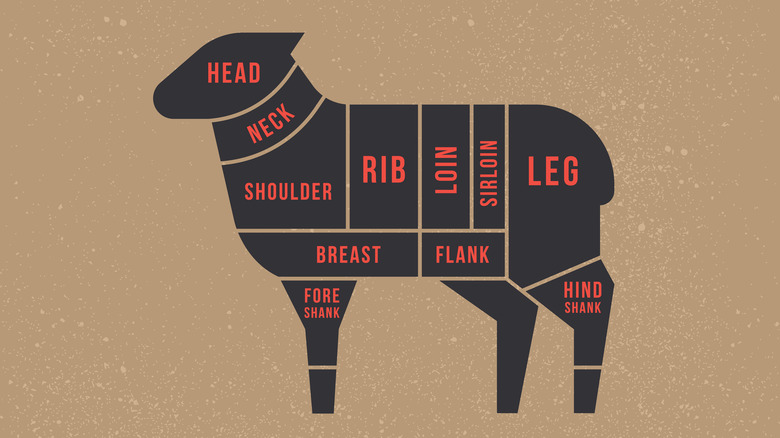

Different cuts of mutton

As a general rule of thumb, there is some consistency between cuts of lamb and mutton. How these cuts are prepared may vary due to how tough and fatty they can be when obtained from mutton. The shoulder, chuck, and shank, a piece sourced from the bottom of the leg, are tough cuts of meat that require low and slow cooking to tenderize them. The shank is usually left intact, while the shoulder and chuck can be sold whole, deboned, cut into chops, or cubed into smaller chunks for stewing.

The rack, which comes from the ribs, is a prized cut often "French trimmed," meaning all the fat is removed to reveal the bones around the exterior. Another highly tender and sought-after portion of mutton is the loin. This can be served whole, a preparation known as a saddle, or cut into chops.

The rump, obtained from the hindquarters, can be stewed or cut into chops. The remaining leg can be left bone-in or butterflied and deboned. This is typically roasted or grilled in its entirety.

The undercarriage of mutton, which includes the flank and breast, is often quite cartilaginous, making it best suited for grinding. The neck and head have morsels that are delicious when properly cooked, like the cheek meat. These often require extensive marinating and long cooking times but can be delectable in dishes like kebabs and stews.

How to cook mutton

While cuts of mutton are similar to those of lamb, the way you cook them is vastly different owing to the increased amount of muscle fiber, fat, and connective tissue in a more mature animal. The uninitiated will often attempt to substitute mutton for a recipe that calls for lamb. This will not work. The meat will come out dry and tough, or the flavor will be overwhelmingly gamey.

Mutton is best suited to low, slow cooking techniques where muscle fibers and collagen in the connective tissues can begin to break down. Braising and stewing is always a good idea, particularly for cuts from the rump, shoulder, chuck, shank, neck, and head. More tender cuts, like the loin, rib, or leg, can be roasted, grilled, or smoked as long as you do not overcook the meat. We generally cook our meat from medium rare to medium in these instances. The same goes for kebabs and burgers to keep them juicy and flavorful.

You will often find that mutton is quite intensely seasoned or cooked alongside dried fruits. Using bold, earthy spice blends, like masala curry and ras el hanout, helps tame the aggressive gamey flavor of mutton. Dried fruits will rehydrate and begin to break down in the cooking process. This creates a luscious sauce and sweetens the dish, tempering the assertive-tasting meat. Whatever you do, never be shy about spicing mutton. This is not the place for a delicate hand.

What does mutton taste like?

Mutton is often described as having a flavor similar to other game meats, like venison. For this reason, many shy away from consuming it. While it is true that the taste of mutton is more aggressive than that of lamb when well-raised, slaughtered, and cooked, we think it is far more flavorful and nuanced. For this reason, we prefer it over lamb.

Sheep enjoy foraging for food. Purchasing meat from a farm that allows its flock to roam freely about the pasture will inevitably produce more subtly-flavored meat because it has had just a bit more exercise. The more diverse an animal's diet, the more interesting the flavor of its meat after slaughter. A study in Frontiers in Nutrition also suggests that meat from pasture-raised animals is more nutritious and sustainable, which is a plus for those concerned with the environment and our health.

If you are worried about animal welfare, you might consider seeking out mutton that has been slaughtered according to Halal or Kosher guidelines. A study from Well Being International suggests that the stress an animal incurs throughout its life and during slaughter may result in lower amounts of lactic acid in the meat, adversely impacting its flavor.

Finally, know how your meat is butchered. There is some indication that allowing the cuts to age for a few days after being butchered will help tenderize them and improve the overall flavor of the final product.

Nutritional information for mutton

Per Healthline, mutton can be a marvelous nutrient-rich protein source when consumed in moderation. Depending upon the breed of animal and how it was raised, a 100-gram serving has nearly 26 grams of protein.

Like other sources of red meat, mutton may contain significant amounts of fat, including high amounts of the ruminant trans fat known as conjugated linoleic acid (CLA). According to Meat Science, these ruminant trans fats have been linked to potential health benefits, including anti-cancerogenic, antidiabetic, and anti-atherogenic properties.

Mutton also contains significant amounts of vitamin B12, selenium, zinc, niacin, phosphorus, and iron, which are necessary for myriad systems within the human body to function efficiently. Additionally, it is high in creatine and the antioxidants taurine and glutathione. Creatine, in particular, has been linked by Endocrine with improving bone density and muscle formation.

Contraindications may include a potentially increased risk for heart disease associated with the regular consumption of increased saturated fats found in red meat and a minor cancer risk associated with eating overcooked or charred meats. Both of these are still up for debate, although since mutton is typically cooked low and slow, you won't likely be ingesting any burnt pieces of meat.

Mutton recipes

Our first introduction to mutton was in Morocco. There, you will find it in various iterations, from sheep's head soup to a local delicacy known as Mechoui, a dish featuring a whole sheep that is roasted in a pit and then served with generous helpings of ground cumin.

You can recreate the flavors of Morocco at home with this take on garlic mutton or a tagine of kefta with lemons and spices. Kefta is meatballs delicately seasoned with grated onions, fresh herbs, cumin, cinnamon, and cayenne for a sweet and savory flavor. While this recipe calls for lamb, it would be executed with ground mutton in Morocco. Poaching the meatballs in liquid and lemon juice will keep them moist and tender.

For a recipe with a French flair, substitute chunks of the mutton shoulder for the meat in this venison bourguignon recipe. Again, by slow-cooking the meat in an acidic liquid like red wine, you will end up with delightfully tender and delicious mutton.

For a Mexican-inspired dish, use mutton instead of goat meat in an authentic Jaliscan birria recipe. This is the place to take advantage of some of the more unusual cuts of mutton, like innards or neck meat, which may take a bit more time to cook to become soft and delectable. Before stewing in a clay pot for hours, the mutton is marinated in an adobo made from orange juice, chili peppers, spices, and animal crackers. The final product will melt in your mouth. Eat it with fresh corn tortillas, a spicy salsa, and a shot of good tequila.

Where to buy mutton?

The subject of where to purchase mutton is a bit challenging to discuss. Depending upon where you live, the answer may differ. If you live in a rural area, you may be able to access a sheep farmer directly and special order mutton from them. We have done this with a local farm, although we were met with some hesitancy, as the farmer was accustomed to processing sheep at around six months of age.

If you live in a more urban setting where you can visit a local butcher shop, the butcher will likely be able to source mutton for you. But plan accordingly, as it may take some time to get the meat. The primary benefit of purchasing meat from a butcher shop is that you can request that it be processed according to your wants and needs. For an additional cost, they will be happy to debone a leg of mutton or pre-cut stew meat for you.

Finally, if you are having trouble locating the meat locally, many farms sell mutton online. Most of these will be seasonal and cost a bit more, but you will be able to guarantee you are getting a premium product. Just be sure to factor in shipping, which is likely by weight and will cost more since the meat needs to be packaged in dry ice or another cold packaging option to arrive safely.

How to store mutton

According to the USDA, ground or organ meats should only be stored in refrigerators for one to two days. Roasts, steaks, and chops can last for up to five days. The most important aspect of storing meat is to keep it in packaging that minimizes exposure to air. Butcher paper or styrofoam packaging is fine, but if you aren't sure, you can always repackage meat in a freezer bag with all the air removed.

We recommend freezing your mutton if you do not plan to cook it within five days. To do so, always repackage it in a freezer bag and remove any excess air. Be sure to mark the date on the bag before putting it into the freezer. Meat should last in the freezer for up to one year.

You should always thaw meat in the refrigerator. Never allow it to sit on the countertop or try to cook a partially frozen piece of meat. You should also never refreeze meat after it has been thawed. If you forget to plan ahead and only have a small portion of meat that weighs less than 4 pounds, submerge it in a bowl of cold water and thaw it on the countertop. This should take no longer than an hour.

Meat that has already been cooked should be kept in the refrigerator in an airtight container for up to four days. Otherwise, place the meat in an airtight container in the freezer for longer-term storage.