The Complete And Fascinating History Of Corned Beef

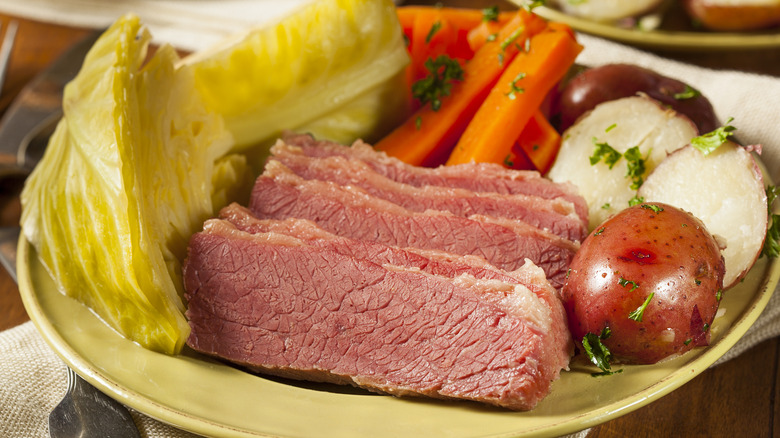

A big part of why celebrating holidays is so fun and satisfying is the cultural unity from everyone engaging in the same traditions, putting up the same decorations, and eating the same foods. As Thanksgiving has its earth tones and turkey dinner, St. Patrick's Day has its green, shamrocks, parades, beer, and corned beef and cabbage. Officially the Feast of St. Patrick, a day in the calendar of the Roman Catholic Church to honor the patron saint of Ireland, is celebrated every March 17. The day brings with it a celebration of Irish culture and Irish-American heritage. And a big part of that is eating Irish foods, like potatoes, cabbage, and corned beef — that distinctively pink and extremely salty hunk of meat.

How and why so many people in the United States commemorate St. Patrick's Day by feasting on corned beef is a long and complicated story, one that doesn't follow a direct line from Ireland to America. Here's the cultural and culinary history of that not exactly authentic but most Irish of dishes, corned beef.

They've been salting beef in Ireland for centuries

Preparing beef for consumption by means of preserving it first through large quantities of salt goes back at least more than 1,300 years. The "Crith Gablach" is a collection of some of the earliest guidelines and laws in Ireland, and was assembled around the year 700 A.D. Bosall, or salted beef, rates a mention. According to "Irish Corned Beef: A Culinary History," there were no salt mines in Ireland, so the salt used for beef preservation was derived by burning seaweed, plentiful in and around the island civilization. Lighting seaweed aflame and turning it to ash allows the salt to be separated out, and that was used to treat meat.

Additionally, the 12th century Irish poem "Aislinge Meic Con Glinne" mentions the use of salt in the preparation of beef, as well as pork, specifically bacon. In ancient times, beef was salted and then left to set in holes dug out of peat bogs, which was also the method by which Irish farmers would preserve butter. Nevertheless, beef wasn't a regularly eaten food among average Irish people in the Middle Ages. Cows were valued as dairy animals and beasts of burden, and considered sacred in Irish-Gaelic culture. By and large, cows were slaughtered only when necessary, after they'd grown too old to be useful in other ways.

English laws led to widespread salted beef production in Ireland

For hundreds of years, Irish food remained what it had been. But then came the 12th century Norman invasion of Ireland, and the subsequent occupation by English forces. The English crown would fully exert its authority in 1541 when Ireland's independent parliament made England's ruling King Henry VIII its monarch as well to quell an uprising. Over the next decades, large numbers of Protestants emigrated from England and Scotland into Ireland, taking land from native Irish Catholics.

English rule transformed the way food was produced and exported in Ireland with the passage of the Cattle Acts in the 1660s. It was henceforth illegal to ship live cattle from Ireland to England, creating an abundance of beef cows in their place of origin so pronounced that the cost of making salt beef cratered. Around the time of the Cattle Acts, Ireland enjoyed cheap salt as well. The mineral was taxed at 10% of the rate that it was in England, so mass quantities of quality product could be shipped into Ireland. Cattle producers had the high volume of beef and salt necessary to introduce large-scale salted beef production, enough to meet demand across Europe. The chunks of salt used to preserve meat were so large that English exporters in Ireland thought they looked like kernels of corn. And so the product was renamed "corned beef." (There's no actual corn in corned beef.)

Historically, the Irish didn't eat a lot of corned beef

When England took over Ireland in the 16th century, it soon enacted a series of rules called Penal Laws. The population of Ireland primarily adhered to Roman Catholicism, and after the spread of the Reformation — a religious movement that established Protestant Christianity in direct opposition to the Catholic Church — England passed laws to penalize practitioners of the old faith. English authorities took the land of Irish citizens away and set up plantations that looked like the old lords-and-tenants, feudal system.

The occupying government essentially turned much of Ireland into English farmland, with the local farmers ordered to grow as much beef as possible. The meat had been a dietary staple in England since the time of Roman rule 1,500 years earlier, and Irish farmers helped meet the demand on the other side of the Irish Sea. While much of that beef would be corned beef, Irish people didn't eat a lot of the stuff at this time. Not only had beef not been a major part of the Irish diet traditionally, but they couldn't afford it — it was out of the price range of the low-waged local workforce. The potato was a main source for sustenance in Ireland during English rule, and if on the rare occasion meat was consumed, it was bacon or salted pork, which were significantly less expensive to raise and purchase than was beef.

Ireland's loss of one crucial food led to the adoption of corned beef thousands of miles away

England began to abolish its highly restrictive, anti-Catholic Penal Laws in Ireland in 1791, but Irish cuisine had already been settled: The island relied heavily on the potato, as well as cabbage, and to a lesser extent pork. Beginning in 1845, a devastating tragedy took hold in Ireland, threatening the food supply, economy, and millions of lives. Around half of the potato crop of 1845 was destroyed and approximately 75% of the harvest in the seven years that followed. Between 1845 and 1852, a million Irish people died as a result of the Irish Potato Famine, or Great Hunger. To avoid starvation, another one million residents left the country, emigrating in mass numbers to the United States.

Large swaths of Irish emigrants settled in neighborhoods in New York City in the mid-to-late 19th century, alongside Jewish people from Eastern Europe. The latter brought with them salted brisket, a slight variation on traditional Irish-style corned beef. Irish people found beef in the United States to be much more plentiful and affordable than it had been in their country of origin. They could suddenly afford to partake in the reasonable facsimile of the dish they had been unable to consume in Ireland. Jewish-style corned beef served at New York butchers and delis quickly became a part of the Irish-American experience.

Contemporary corned beef is very different than historical corned beef

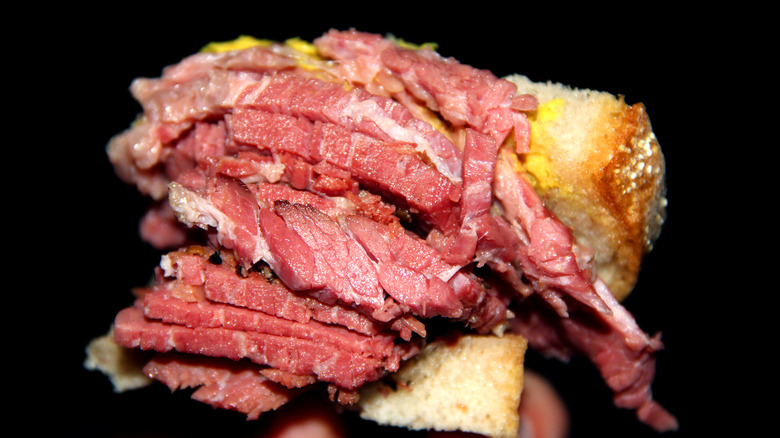

The corned beef sold in grocery stores and sliced into sandwiches at shops and butcher counters across the United States follows the Jewish deli tradition. That means it's made out of the brisket cut of beef — a substantial and meaty portion found in the front or breast area of a cow. Simple cooking or roasting isn't enough to make brisket edible or enjoyable. In its role as a major element of Texas barbecue, brisket is slow-cooked or smoked to make it soft and tender. To transform the naturally tough brisket into smooth and chewable corned beef, it's treated with large amounts of salt or left in a heavily salted brine solution.

But that's just modern, Jewish deli-style corned beef. Traditionally, in Irish cuisine, the cut used to make what would eventually become corned beef was silverside. Found on the cow's hindquarters, silverside is so named because it's covered in a silver-colored membrane. Because cows in the 20th century United States are butchered in a different way than they were in Ireland hundreds of years ago, silverside isn't a standard cut of beef in 2020s America. As far as taste and consistency go, it's similar to rump roast or topside.

Corned beef sales skyrocket near St. Patrick's Day (but only in the U.S.)

St. Patrick's Day took off as a holiday in the United States because so many Americans claim some Irish lineage, according to the National Portrait Gallery. In 1762, the first St. Patrick's Day parade was held in New York City, and as Irish immigration climbed over the next century, the holiday grew into a day to celebrate Irish heritage. After corned beef became entrenched in the Irish-American diet, traditional Irish foods like potatoes and cabbage rounded out the definitive Irish meal for St. Patrick's Day.

Corned beef is thus a quintessential Irish-American dish — but not a quintessential Irish dish. According to "Irish Corned Beef: A Culinary History," corned beef as a dinner isn't especially popular in Ireland, on St. Patrick's Day or during the rest of the year. In the U.S., corned beef peaks in popularity around March 17 — both St. Patrick's Day and National Corned Beef and Cabbage Day. According to Supermarket News, 85% to 90% of a grocery chain's corned beef sales may come in mid-March.

What's the difference between corned beef and pastrami?

Corned beef and pastrami are very identical meats. Both are made of beef, taste salty, finish the production process in a shade of pink, and are sliced thin and piled high in sandwiches popularized by traditional Jewish delis. But corned beef and pastrami are decidedly not the same. Corned beef starts with brisket, a cut from the breast part of the cow. It's cured with a salt-based brine mixture that imparts flavor via the addition of herbs and spices like mustard seed, coriander, cloves, allspice, and peppercorns. The salt tenderizes the brisket, transforming it from a tough and chewy cut into something quite soft and tender.

Pastrami is made with a similar salt-and-spice curing process. However, it originates with a cut of beef culled from a completely different part of the cow. The deli favorite starts out as a shoulder cut called deckle, or, alternately navel meat, found below the cow's ribs. That meat is dried, rubbed down with spices, and then, it's smoked. Corned beef differs in that final step in that it's boiled.

What's the deal with canned corned beef?

Millions of people are most familiar with canned beef in its canned form. Packaged foods giant Libby's began in 1868 humbly, producing and selling just one thing, corned beef in a tin can. As salting beef was one form of preservation that gave way to the latter method of canning, the product could last a long time and be shipped all over the world. A meat processing plant established in 1866 in the port area of Fray Bentos in Uruguay became the world's most prolific tinned corned beef processor, according to "Irish Corned Beef: A Culinary History." In the 1920s, that factory came under British control, and in World War II it was able to provide a steady supply — as many as 16 million cans a year — of cheap, shelf-stable, portable protein to Allied troops.

Nicknamed "bully beef" in England, inexpensive canned corned beef made in South America and shipped globally became a dietary staple in the Philippines, and, somewhat ironically, Ireland — where corned beef in its original form developed. Just after World War II, according to The Jewish News of Northern California, the Israeli Defense Forces produced a corned beef product called Loof. It was kosher, permissible under Jewish dietary law, and served as an alternative to Spam. That other canned meat was widely consumed by soldiers in World War II, but as it was made of pork, it wasn't allowable in the kosher system.

Corned beef sandwiches aren't the same everywhere

Corned beef originated in Ireland, but was popularized by the governing English, who also gave the dish its name. English industrialists similarly helped spread canned corned beef to all corners of the world, and that's the form of the food that seems to have resonated most in the British cultural consciousness. If one were to order a corned beef sandwich in the U.K., they wouldn't get salted whole brisket, thinly sliced and stacked tall between two pieces of bread. They'd receive one made with the mushy, Spam-like canned stuff, and probably also topped with vinegar or a pickled chutney. To receive a familiar corned beef sandwich in the U.K., diners ought to scour the menu for a salt beef sandwich.

The salt beef sandwich, or a corned beef sandwich, is synonymous with another kind of specialty dish, the Reuben. Sometimes made with pastrami but traditionally with corned beef, that sandwich was invented in Omaha, Nebraska, in the 1920s. Chef Bernard Schimmel of the Blackstone Hotel came up with the idea to feed some gathered hungry poker players. One of them was named Reuben Kulakofsky, and he's the namesake for the sandwich consisting of corned beef, Swiss cheese, Russian dressing, and sauerkraut on rye bread.

A corned beef sandwich traveled into space

According to The New York Times, only a relative handful of humans have ever left the planet — around 600 — either as space tourists or selected for astronaut programs to work on space missions. As such, only a few foods, including ice cream, have been to space as well, and corned beef is one of them. According to Discovery News, the food onboard NASA's Gemini III space capsule mission in 1965 included hot dogs, chicken, brownies, and applesauce, all stored in tubes and designed with certain concerns in mind, namely a lack of offensive smells and a lack of likelihood to produce instrument-clogging crumbs.

Two hours into the mission, as Commander Gus Grissom discussed the menu with Pilot John Young, the latter unveiled the corned beef on rye bread sandwich he'd smuggled to space in a pocket of his flight suit. News got out about the forbidden corned beef sandwich, and Young later earned the ire of a Congressional Appropriations Committee for the danger his meal could have caused. Senator George Shipley stated, "My thought is that after you spend a great deal of money and time, to have one of the astronauts slip a sandwich aboard this vehicle, frankly, is just a little disgusting."

Corned beef is fit for a president

The influence of an American president can be substantial, and the popularity of corned beef in the United States could be traced in part to the approval of the Commander-in-Chief. According to Mount Vernon, now a museum but what was once the residence of President George Washington before the White House opened, first lady Martha Washington served cold corned beef to guests for breakfast. And on the day of Abraham Lincoln's first presidential inauguration in March 1865 — right around St. Patrick's Day — he ate corned beef and cabbage for lunch, according to the Wall Street Journal. President Grover Cleveland, according to the Cape Cod Times, requested a meal of corned beef and cabbage in lieu of his scheduled dinner one night when he could smell it cooking in the servants' kitchen.

In 2010, according to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, President Barack Obama became embroiled in a corned beef scandal. It was frowned upon by culinary purists when Obama visited a deli in Miami and reportedly ordered a corned beef sandwich with mayonnaise. A representative of the White House later declared that the writer who filed the story had made an error, and that the president had ordered a more proper corned beef with mustard for himself; the mayo-slathered one had been for his campaign companion, Rep. Kendrick Meek.