The 20th Century American Cookbooks Now Considered 'Kitchen Bibles'

Chances are everybody reading this has at least owned or relied on a cookbook or two, but the chances that we actually use them on a regular basis are slimmer. Cookbooks are one of those things we often buy in a fit of aspiration that doesn't end up sticking around. We say to ourselves, "boy oh boy, today's the day that I master pie crust!" only to put it off for a week, then two, then forever. We should choose our cookbooks diligently, considering what we like to eat, what ingredients we have access to, and how much patience we have, to make sure that we actually use them. We also need to consider how we like to learn, whether we like an authoritative voice telling us exactly what to do or a gentler, more flexible tone.

To help you fill out your cookbook collection, we're listing five 20th-century books that many Americans treat with biblical reverence. Most of them rank among the best-selling cookbooks of all time, and they cover a lot of bases, so there should be something here for everyone.

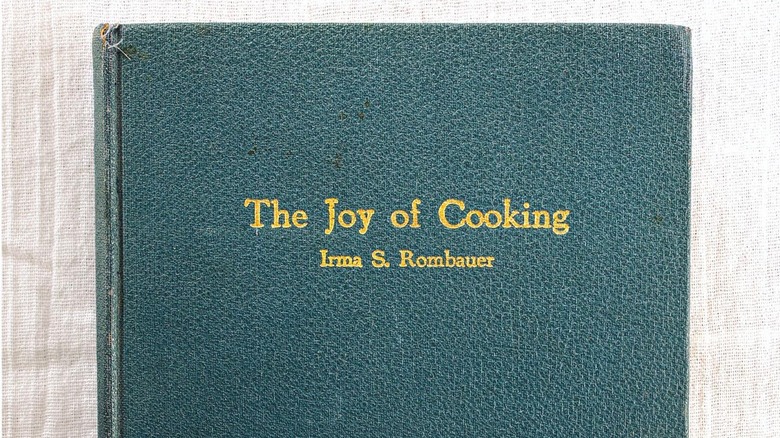

Joy of Cooking

It seems like every home in America has its own copy of "Joy of Cooking," handed down through so many generations that the spine is peeling off. Originally self-published in 1931 by St. Louis resident Irma S. Rombauer, the cookbook's title comes from a surprisingly profound place. The word 'joy' was eye-catching considering the era it was written: the Great Depression. This was an especially difficult time for Rombauer, who lost her husband in 1930. To cope with her grief and find a new sense of purpose, she spent the next year compiling her favorite recipes in a collection to share with the world.

Writing in a witty and personable tone, Rombauer presented cooking not as a chore to be done on top of all life's demands, but as a joyful and fulfilling pastime. As of this writing, the book is on its ninth edition and contains about 4,600 recipes, although the 1975 version is the most popular. It's about as all-purpose as a cookbook gets, too, packed with traditional European-influenced American fare, but more importantly, brimming with useful tips, conversions, reference pages, and brief histories of different ingredients. "Joy of Cooking" has been so influential that the New York Public Library named it one of the 150 most influential books of the 20th century – the only cookbook to make the list.

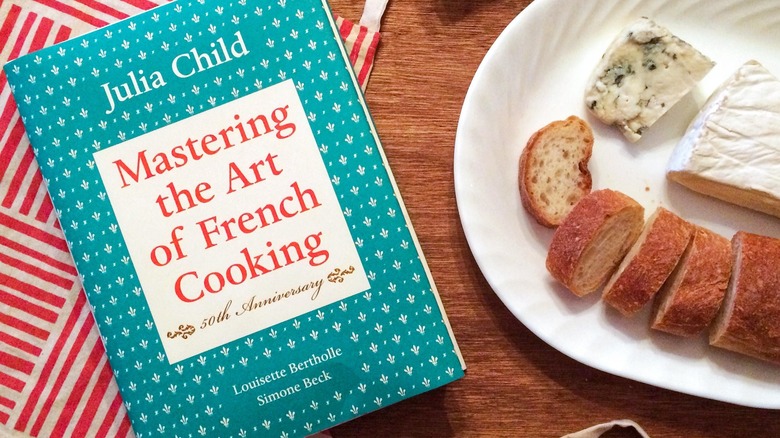

Mastering the Art of French Cooking

No individual has had a greater impact on culinary media than Julia Child. She was the first true celebrity chef, presiding over a small media empire that included multiple television series and cookbooks, and it all began with "Mastering the Art of French Cooking." Published in two volumes (the first in 1961 and the second in 1970), the landmark book has been credited with introducing French cuisine and techniques to American home cooks. Child tends to get all the credit for it, but she actually had two co-authors: Simone Beck and Louisette Bertholle. The three women met when Child was studying at Le Cordon Bleu in Beck and Bertholle's native France.

Early-'60s America was no place for gourmands. This was the age of TV dinners, when cooking intentionally leaned into processed foods. "Mastering the Art of French Cooking" was instrumental in changing this fact, making so-called haute cuisine approachable and enjoyable. It was so influential that PBS executives asked Child to host a television show based on her book. The result, entitled "The French Chef," laid the foundation for culinary television: Food Network, Cooking Channel, and even TikTok kitchen tutorials would not exist as they do today. In modern times, when so much value is placed on recipes that require as little time and as few ingredients as possible, some entries in "Mastering the Art of French Cooking" seem dauntingly laborious, but the simpler dishes and the fundamental techniques have proven timeless.

Moosewood Cookbook

These days, bookstores are packed with great resources for vegetarians, and famous chefs like Yotam Ottolenghi, Chloe Coscarelli, and Bryant Terry have made their names through plant-based meals. However, this is a recent development, as culinary media has, by and large, been slow to catch up to vegetarians and vegans. That's what makes "Moosewood Cookbook" so ahead of its time. Moosewood Restaurant opened in Ithaca, New York in 1973, and was a distinct counterculture landmark. It operated on a co-op model that broke from the standard brigade de cuisine hierarchy developed by Auguste Escoffier, and none of its staff was professionally trained. The kitchen's vegetarian menu was built on the co-op members' family recipes – the same recipes that make up this cookbook.

A year after Moosewood opened, the collective's Mollie Katzen gathered all of the recipes they'd been using and transcribed them by hand into one large volume. Every subsequent copy of the book retains her distinct handwriting and illustrations. At a time when very few cookbooks catered to vegetarians, "Moosewood" was revolutionary, and it now stands as a sort of historical document, chronicling the early state of contemporary American vegetarian cuisine so that modern readers can clearly see how much has changed. Its food is still as relevant today as ever, though, and New York Magazine claims that "no one cooking vegetables can afford not to read" it.

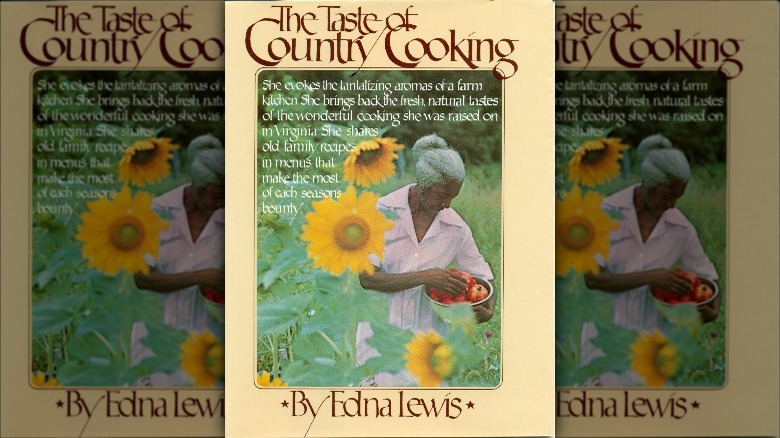

The Taste of Country Cooking

Edna Lewis was, in the words of her NPR obituary, "the first lady of Southern cooking," a title she earned through her 1976 masterpiece, "The Taste of Country Cooking." Growing up in Freetown, Virginia, a small farming community established by a group of freed slaves that included her grandfather, Lewis learned the virtues of local and seasonal ingredients long before the modern farm-to-table trend began. The book is divided into four sections, one for each season. The spring menu employs wild mushrooms and field greens, summer brings ripe garden veggies and fruit, the fall harvest welcomes sweet potatoes, while winter is the season for hearty soups and stews.

"The Taste of Country Cooking" is packed with classic Southern comforts like corn pone, rhubarb pie, and chicken and dumplings, but for many readers, the most impactful part of the book isn't the actual recipes. Lewis uses the seasonal framework to narrate a year in the life of Freetown, and although she spent much of her adulthood in the New York City restaurant scene, she used stories from her youth to maintain a connection to the South. Rather than present each recipe in a vacuum, she grouped them into different menus, some dedicated to special occasions such as Christmas Eve, Midsummer, and Emancipation Day. With this unique approach, Lewis makes "The Taste of Country Cooking" into more than a cookbook. She makes it a life book.

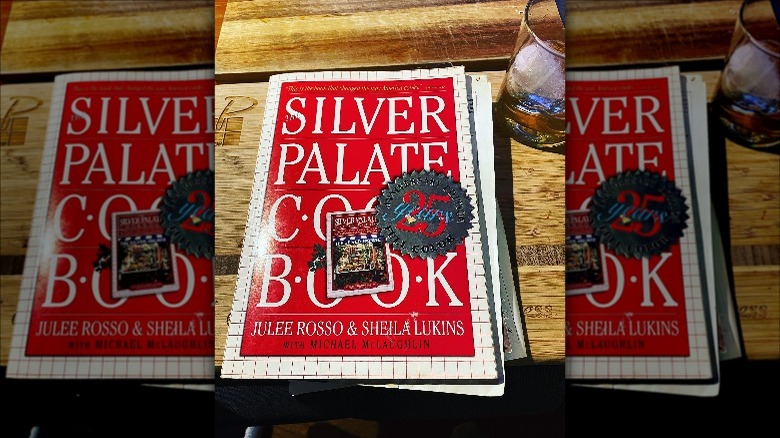

The Silver Palate Cookbook

At the dawn of the 1980s, American home cooking was still largely dependent on processed and pre-packaged ingredients, while the concept of 'fine dining' was pretty much limited to French food. "The Silver Palate Cookbook" changed that, and thank goodness it did, or we might never have tried things like arugula and pesto that are now common delights. It was written in 1982 by Julee Rosso and Sheila Lukins, proprietors of a Manhattan specialty foods store whose clientele included John Lennon and Yoko Ono. The recipes drew on international influences, particularly Mediterranean cuisine, but many of the specific dishes were original inventions of Rosso and Lukins, such as Chicken Marbella. Combining global flavors with an influence on fresh produce, they laid the groundwork for modern American cuisine.

"The Silver Palate Cookbook" also shines through its unique style. Lukins was a caterer, so she approached food with a party in mind. All of the recipes are meant to serve eight or more guests. It's all written in a warm and friendly tone that contrasts with the dry authoritarianism of many recipes. The authors actively encouraged readers to experiment with their recipes and change them according to personal tastes. There are helpful notes printed in the margins of almost every page, alongside the book's iconic images, which were all hand-drawn by Lukins since they could not afford professional photography.