12 Steakhouses That Time Forgot

Starting in the mid-20th century, and continuing to this day for a lot of people, the very peak of luxurious dining and a classy night out begins and ends with a steak dinner. A prime cut of a nice sirloin, with a baked potato, roll on the side, and a salad — prepared table-side, in the kitchen, or obtained and assembled by the customer themselves at the salad bar — is the definitive dinner out, reserved for special occasions like promotions, birthdays, and anniversaries. If one of these all-American steakhouses was really fancy and customer-minded, they'd also likely have a few fish options, a classic dessert or two, and a decent wine list.

Steakhouses, high-end and chef-branded ones, remain an American culinary institution, but they're few and far between now. In the 1970s and 1980s, every medium-sized city had at least a couple of outlets for a reliable national steakhouse chain. For better or for worse, that era is long gone. Once mighty and meaty steakhouse chains and famous independent establishments alike are disappearing. Here are some forgotten steakhouses that closed up shop entirely a long time ago, or seem to be headed in that direction.

British-inspired Steak and Ale was the place to be in the '60s and '70s

Opening in Dallas in the 1960s at a time when steak dinners were widely seen as a rare and expensive indulgence, Steak and Ale brought the steakhouse to the suburbs at affordable prices. The chain's old English-style dining rooms were also a launch point for now common restaurant ideas, like a lunch menu that costs less than the dinner menu, free refills on soda, and an all-you-can-eat salad bar, in addition to steaks, pasta, wine, and beer. After a takeover by Pillsbury's restaurant division, nearly 300 Steak and Ales populated the American dining landscape by the mid-1980s.

Steak and Ale was a victim of its own success, slowly forced out of business by the growing and competitive casual dining scene it helped create. In 2008, owners Metromedia Restaurant Group filed for bankruptcy. According to the Dallas Morning News, all 58 Steak and Ale locations shut down immediately, with no notice given to employees and food "left rotting in refrigerators."

York Steak House used to rule the mall

Berndt Gros and Eddie Grayson opened the first York Steak House in 1966. Eatery number one debuted in a restaurant pod in Columbus, Ohio called The Patio, and the idea of opening new locations directly adjacent to competitors became a business model for York Steak House, which expanded rapidly in the 1960s with places in the then-emerging retail trend of shopping malls. General Mills Restaurant Group bought the York Steak House chain in 1976 and set out to make a national concern out of it, topping out at almost 180 units, nearly all of them in malls. Customers could choose from a number of cuts of beef (or chicken or fish), which came standard with a potato option, a roll, and a trip to the salad bar.

But then malls evolved, with many installing food courts that offered numerous fast food options at cheaper prices than even a budget steakhouse like York. In the 1980s, York closed down restaurants as quickly as it had once opened them. As of 2023, only one outlet remains — in the chain's original hometown of Columbus, Ohio.

Beefsteak Charlie's spoiled customers until it couldn't anymore

The idea of all-you-can-eat anything is attractive if not irresistible to restaurant patrons seeking to fill their bellies and get good value for money. Beefsteak Charlie's delivered on that. Once a single location in 1910, a restaurant chain started up in the mid-1970s when restaurateur Larry Ellman learned that the original's name wasn't trademarked, prompting him to rename a small chain previously known as Steak and Brew. The new Beefsteak Charlie's became immensely popular for providing an almost ridiculous abundance of steakhouse amenities. In addition to hugely portioned platters of ribs, chicken dishes, and steaks at competitive prices, Beefsteak Charlie's boasted an all-you-can-eat salad bar — with endless shrimp included – and unlimited refills on ice cream, soda, beer, wine, and sangria.

There was little hyperbole in the chain's ads. They featured an actor playing the gregarious, food-pushing Beefsteak Charlie. One ad famously promised customers, "You're gonna get spoiled!" By 1984, there were more than 60 Beefsteak Charlie's locations operating on the East Coast. But, by 1987, things were looking bleak. Bombay Palace Restaurants bought the struggling chain, but it's hard to turn a profit when so many parts of the menu are free and unlimited. Bombay Palace filed for bankruptcy in 1989, and by the dawn of the 21st century, Beefsteak Charlie's was gone.

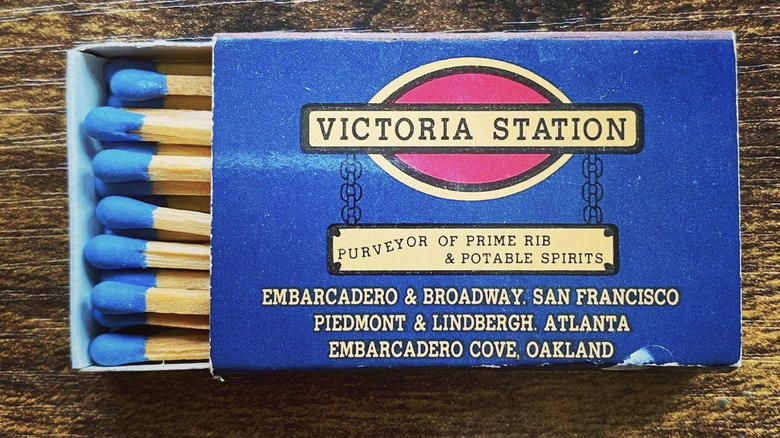

All aboard for Victoria Station

Diners looking for a night out at a steakhouse had a lot of options from which to choose in the mid-20th century U.S., but Victoria Station offered a unique hook — its dining rooms were built out of old boxcars and sported a nostalgic, trains-and-railroad theme. A group of graduates of the School of Hotel and Restaurant Administration at Cornell University opened the first Victoria Station steakhouse in San Francisco in 1969. By the late 1970s, nearly 100 Victoria Stations were up and running (or standing still and serving steak and all the trimmings) around North America.

After topping out at that robust level, business chain-wide started to decline. Expanding too far too quickly led to a financial crush. By 1981, the business was operating with a $6.3 million yearly loss. A change of top management didn't help much, and Victoria Station filed for Chapter 11 reorganization in 1986, closing the vast majority of its remaining restaurants. A solitary restaurant stayed open in Salem, Massachusetts, finally closing down in 2017. It was a blow for the community, especially Salem's Children's Charity, which had been using the restaurant to host its annual Christmas party for over two decades. "For Salem Children's Charity's sake, it's a disaster," board member Brendan Walsh told The Salem News. "We're scrambling now, and we may yet come up with something."

After a recession, only one Lone Star Steakhouse and Saloon is left

The family-oriented, sit-down, midscale chain model came for the steakhouses in the 1990s, with places like Texas Roadhouse and Outback Steakhouse dominating that sector both then and now. There was another major entry in that realm, and it was Lone Star Steakhouse and Saloon. The fare was exactly what was promised — steaks, seafood, salads, and other elements of a big, Texas-style dinner. Founder Jamie B. Coulter used the profits he made as a franchisee of multiple Pizza Huts to franchise Lone Star, a North Carolina restaurant opened by Creative Culinary Concepts in North Carolina in 1989. When Lone Star Steakhouse and Saloon launched as a chain in 1992, it did so with eight outlets. By the end of 1990s, the company could boast the existence of 265 Lone Star Steakhouses across the U.S.

The novelty faded quickly, however, and the value of the company plummeted. By early 2009, as an economic crisis hit the United States, Lone Star had 179 outlets left, and then it closed 27 of them. By January 2017, only 16 sites remained. As of 2023, a single Lone Star still opens its doors on the U.S. island territory of Guam.

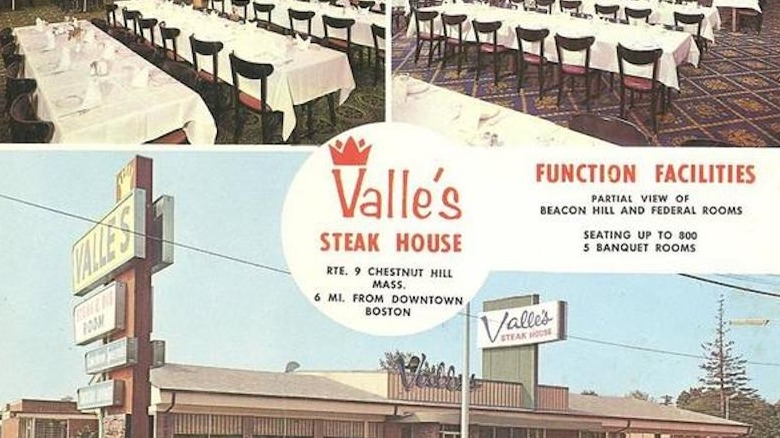

Valle's Steak House was a New England institution

Valle's would one day become a multi-outlet chain of gigantic steakhouses in Maine, Massachusetts, and Connecticut that served big steaks at inexpensive prices to a large and continuous volume of customers. The first Valle's Steak House was a 12-seat restaurant in Portland, Maine, opened by owner-operator Donald Valle in 1933. Business was so good that by the end of the 1930s, Valle could open a second, bigger restaurant and also convert a nightclub into another sizable eatery. The average Valle's Steak House took up a lot of square footage, and the company served hundreds of thousands of customers. In 1951, a Portland location sold more steaks than any other restaurant in the U.S. After Valle's expanded with three locations in the Boston area in the mid-1960s, the chain served more than 200,000 people a week and employed 1,300 people.

A few dozen Valle's operated across Maine, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New York by the mid-1970s. But that's when revenues and profits began to slow down. After the death of Donald Valle in 1977, his relatives couldn't afford to pay hefty estate taxes. As the '80s wore on, the Valle family gradually shut down every steakhouse but one in Portland, which stayed open until 2000. It outlasted the last independently operated Valle's, which shut down in 1991.

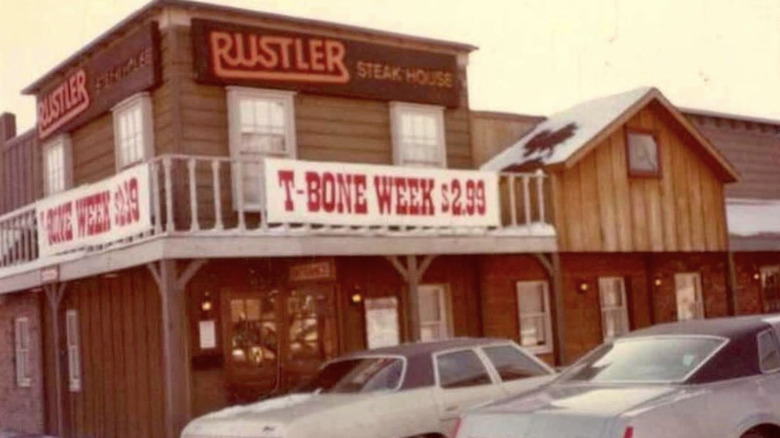

Rustler Steak House lost the Western steakhouse duel

Retired football player Joe Campanella opened Rustler Steak House in 1964, adopting a theme uncommon at the time for restaurants not serving fast food: Old West stuff, like cowboys and ranchers. Gino's, another restaurant chain founded by a retired professional football player in Gino Marchetti, bought Rustler five years later. Under its new owners, Rustler moseyed along but gradually lost market share to other bargain-priced, family-oriented, Western-themed steakhouses, including Ponderosa and Bonanza. The company also spent a lot more money on advertising than it would have liked — the outlets were so far-flung that only expensive national advertising could be utilized.

The recession of the 1970s caused Rustler prices to rise by 12 percent in a single year, and executives tried to cut costs by laying off a large portion of its restaurant-level staff and slashing its marketing budget. The bad economy, higher meat prices, harried service, and a lack of awareness made business suffer. Gino's sold Rustler to the Marriott Corporation, which then turned it over to Tenly Enterprises, which attempted to tone down the Western motif in the 71 restaurants that remained open in 1984. A year later, Rustler was sold again, absorbed into its ascendant competitor, the steak-and-salad-bar chain Sizzler.

Red meat fears and an economic downturn spelled the end for Mr. Steak

One of the first casual sit-down restaurants and steakhouses for the American masses, Mr. Steak opened its first restaurant in Colorado Springs in 1962. It sold USDA "Choice" level steak at prices noticeably lower than that of fine-dining restaurants, which lured so many customers that the chain explosively expanded over the next decade and a half. By 1978, customers packed nearly 280 Mr. Steak restaurants across the United States, with the steakhouse becoming a favorite for birthday parties — you could dine for just $9 on your birthday.

In the late 1970s, the public's attitude toward red meat began to shift. So many people stopped eating beef or cut back on their consumption out of concerns over its possible negative health effects that business at restaurants like Mr. Steak suffered. Seeking to make up for the lost revenue, the restaurant chain greatly expanded its menu, adding so many chicken and fish entrees and health-forward salads that brand identity suffered.

The new direction didn't bring much relief, and the further financial damage of unpaid franchise leases along with increasing debt led parent company Jamco to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in 1987. The chain had shrunk to just 60 units by the time Omnivest International paid $140,000 to acquire what was left of Mr. Steak. Most of those restaurants were converted into Finley's steakhouses.

Dakota Steakhouse was once a Northeastern favorite

Dakota Steakhouse predominantly served the Northeast United States. It opened for business in 1984 with an eatery in Pittsfield, Massachusetts and ultimately expanded throughout Connecticut, New York, and Vermont. Set in the picturesque and woodsy Berkshire Mountains, Dakota Steakhouse appropriately adopted an old-fashioned log cabin as its theme, serving tried-and-true steaks, seafood, and salads in a cozy, rustic atmosphere.

By 2013, all the secondary Dakota Steakhouses outside of the Berkshires had closed down, leaving the original in Pittsfield as the last restaurant standing, albeit barely. The restaurant's parent company had emerged from bankruptcy but still faced impossible-to-overcome financial issues, such as a government seizure of revenues to settle large unpaid tax debt. In April 2013, the Dakota location opened for Sunday dinner service as usual. After every customer went home, management locked the place up and it never opened again.

Bugaboo Creek offered robots and steaks, but it didn't work out

What if some enterprising restaurant company took the animatronics from a Chuck E. Cheese or Showbiz Pizza and applied them to a restaurant with far more adult fare, like steaks and salads? In the 1990s, somebody did, and they called it Bugaboo Creek Steak House. Evoking the look and feeling of a mountain cabin or lodge, the faux-log walls were equipped with animatronic taxidermy-style animal heads, which would occasionally come to life and talk at customers, reeling off facts about the natural wonders of Canada. Characters included Bill the Buffalo, Moxie the Moose, and Timber the Christmas tree.

The first Bugaboo Creek restaurant opened its doors in Warwick, Rhode Island, in 1993. Ownership changed hands until it wound up in the possession of CB Holding Corporation, which filed bankruptcy papers in 2010 and closed down 10 restaurants. Capitol BC Restaurants saved the chain and re-opened 13 outlets. However, by 2016, only two Bugaboo Creek Steak Houses were left open, both in Maine. They both closed in June of that year, shuttering within a week of each other and leaving dozens of employees out of work.

Charlie Brown's is no longer the New Jersey phenomenon it once was

CB Holding Corporation, the final owners of the defunct Bugaboo Creek Steak House chain, also controlled Charlie Brown's Steakhouse at the end of its five-decade history. In 1966, the first Charlie Brown's Steakhouse opened in New Jersey. In three decades' time, New Jersey would be home to 22 Charlie Brown's locations, notably serving steak and prime rib and offering a well-stocked salad bar.

In 2010, citing financial underperformance chain-wide, CB Holding Corp. shuttered 20 Charlie Brown's Steakhouses, leaving just nine open. Those spots trudged along for a decade, and five more popped up along the way. When 2020 began, 14 Charlie Brown's Steakhouses served New Jersey. Following months of strict, government-ordered shutdowns to slow the spread of the COVID-19 virus that year, all but one went out of business. As of February 2023, two Charlie Brown's Steakhouses are operational, one in Scotch Plains and the other in Woodbury.

A celebrity-owned steakhouse for women couldn't cut it in Las Vegas

Actor Eva Longoria got her big break as a member of the cast of the hit ABC show "Desperate Housewives," and she parlayed her fame and fortune into business concerns, including a production company, a high-end tequila, and a couple of classy, expensive steakhouses in the city where tourists go to spend a lot of money: Las Vegas. In 2009, Longoria announced plans to open a Vegas branch of Beso, her Hollywood restaurant. The steakhouse was situated inside of a mall-casino complex on the Las Vegas Strip, but, despite the location and celebrity ownership, it suffered financial issues within a year of opening. In early 2011, Beso LLC filed for bankruptcy. Landry's Restaurants, owner of hotels, casinos, and chain restaurants such as the Rainforest Café, purchased the business.

Landry's set about revamping Beso, teaming up with Longoria and steakhouse chain Morton's to open a new restaurant in late 2012: SHe by Morton's. SHe was supposed to be a steakhouse just for women. What does that mean? The portions of meat were smaller, befitting a woman's supposedly light appetite, and the dessert menus came attached to mirrors, so that female customers could apply after-dinner lipstick touch-ups. In April 2014, the Southern Nevada Health District closed down SHe over food safety violations. Weeks later, Landry's shuttered SHe altogether.