The Complicated Story Behind The US Ban On Beluga Sturgeon Caviar

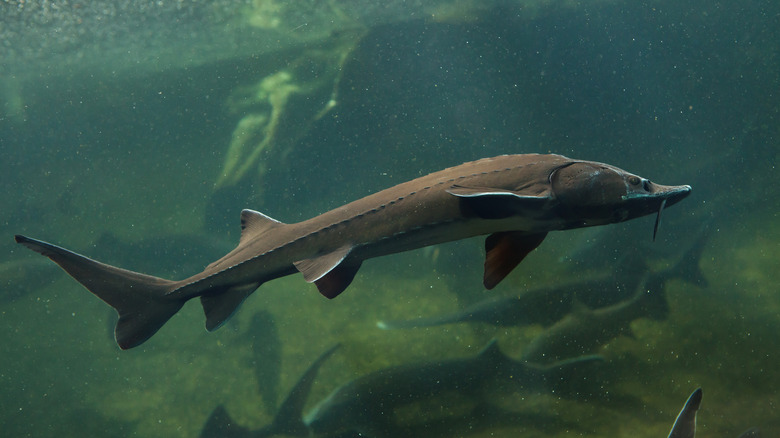

In the late 19th century, when Russia finally emerged from nearly a century of impoverishment under a feudal system, tsars welcomed a new delicacy to their tables: salt-cured roe harvested from the pointy-noised female sturgeon of the Caspian Sea. Due to the limited supply of the species — also known as beluga or beluga sturgeon — the pearls quickly became a luxury that only the wealthiest members of society could afford, according to Caviar Star. A century later, when the Russian aristocracy high-tailed it to France to flee the massacres of the Bolshevik Revolution, they greeted their fellow elite with the expensive product and sparked its popularity there, per the luxury foods and caviar company Petrossian.

While the Russians may have popularized the curing method that gives caviar the delicate taste we know today, they were hardly the first to discover it. According to Petrossian, Persians were the first to consume the same sturgeon eggs from the world's largest lake. Today, highfalutin party hosts around the world might serve the glossy stuff over wafer-thin crackers or potato chips, stuffed into beignet-like doughnuts, or spooned over scrambled eggs.

Not all of them, however, will get to wow their guests with sought-after beluga. According to the National Wildlife Federation, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) has banned American retailers from importing the increasingly rare product since 2005.

Sturgeon have faced a deadly decline

The 2005 ban on U.S. imports of Russian beluga was the first "unilateral U.S. effort" to save the species from extinction, the National Wildlife Federation website explains. Between 1985 and 2005, the conservation nonprofit says beluga experienced a massive decline by nearly 90%. The ban may have helped exacerbate the problem, but it didn't fix it. In 2010, the species was deemed "the most threatened group of animals" on the International Union for Conservation of Nature's (IUCN) red list of threatened species, topping the unfortunate ranks of 18 other threatened species of sturgeon across Europe and Asia.

For Americans with deep pockets and a taste for beluga, only one authentic (read: legal) source remains, located in Bascom, Florida. Insider's Graham Flanagan visited the site in 2020, noting that it's one of the largest beluga farms in the world. It's run by Russian immigrant Mark Zaslavsky, who used to import the species into the U.S. before the 2005 ban; as of this report, he's the proprietor of the sole legally minted beluga farm in the States.

But how does that fly? According to Zaslavsky, his farm harvests sturgeon eggs from the same lot that was originally imported in 2003 and 2004, also known as a "brood stock." Naturally, Zaslavsky is also keen on restoring the beluga population beyond his own farm. Per Insider, his company donated more than 160,000 fertilized beluga eggs to organizations working toward repopulation at the time of the article's publication.

Ethical alternatives to unethically sourced caviar

In 2021, The Washington Post reported that state wildlife officials in Wisconsin knocked back $20,000 worth of illegal caviar, which led to the arrest of one Ryan P. Koenigs, then known as a sturgeon biologist for the state's Department of Natural Resources, following a three-year investigation. Needless to say, illegal sturgeon peddling is a sad but prolific reality for a product that can set you back $35,000 per kilogram, per Insider. In Russia, where sturgeon fishing is also restricted, a group of criminals tried to drive away with 1,100 pounds of caviar stowed in the back of a funeral car, Munchies reports.

Luckily, for those of us who enjoy the finer things in life but have a tight ethical and financial budget, beluga sturgeon caviar isn't the only type on the market. As Eater's Ryan Sutton puts it, "a $500 tin of kaluga won't automatically make you happier than a little $10 jar of trout roe." Petra Bergstein, the founder of The Caviar Company, tells Martha Stewart that it's best to choose domestic caviar if you don't want to break the bank. She recommends roe from wild American sturgeon like hackleback or paddlefish.