The Storied History Of Domino's

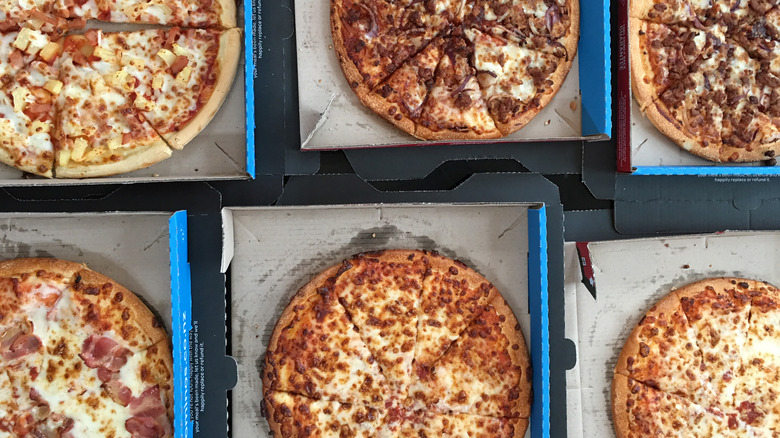

It's one of the best-known names in the vast and competitive American quick-serve scene, because it's one of the most prolific and omnipresent restaurants in fast food history. That's Domino's Pizza — or as of 2012, just Domino's (per PR Newswire) — purveyor of crowd-pleasing pizzas served with a variety of crusts, several sauces, and dozens of toppings. And let's not forget all those comfort food sides like breadsticks, cinnamon sticks, chicken wings, sandwiches, salads, and sodas. As of 2022 (via ScrapeHero), there are more than 6,500 Domino's outlets in the U.S. alone, each one of them cranking out hundreds of pizzas and sides and helping to make millions of people's pizza nights a tasty, affordable, and celebratory affair.

Along with other mega-competitors like Pizza Hut and Papa John's, Domino's has helped spread the popularity of pizza. An obscure Italian dish in the early 20th century, pizza is now synonymous with Domino's, which also normalized the idea of pizza delivery. Domino's history is thick, saucy, and not too cheesy — so help yourself to a hot slice of their story.

Domino's was briefly a family business, and it wasn't called Domino's

In 1960, according to the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, postman Jim Monaghan spotted a pizza takeout store for sale in Ypsilanti, Michigan. He told his brother Tom, a budding entrepreneur, and they bought DomiNick's Pizza from Dominick DeVarti. According to CNN Money, the Monaghans made a $500 down payment and got the rest of the $1,400 price in a loan from Jim's postal workers' credit union. And just like that, Tom and Jim Monaghan owned DomiNick's Pizza, according to Statista. The purchase price also included an education in pizza-craft. "I got a 15-minute lesson in making pizza from Dominick and I was off," Tom Monaghan recalled.

Jim and Tom planned to split the work evenly, though that idea didn't last because it conflicted with Jim's postman day job. "Within about eight months he wanted out," Tom Monaghan explained. He bought out his brother's half of the business by giving him his used Volkswagen Beetle, which was also the company's pizza delivery vehicle.

Tom Monaghan opened two more pizza parlors in the early 1960s, and all three operated under different names. Looking to connect and brand his burgeoning mini-empire, Monaghan put the idea of creating a new name to his employees. In 1965, pizza delivery driver Jim Kennedy came up with the winner, according to The Orlando Sentinel, and it was one that wouldn't require much of a change to the flagship store's sign: Domino's.

Domino's invented the pizza box

The first three restaurants bearing the name Domino's Pizza, formerly DomiNick's Pizza, were just not profitable in the early days, despite doing decent business. According to LiveAbout, the stores primarily served college students — the original location was in the college town of Ypsilanti, Michigan, after all — and co-founder Tom Monaghan decided the best way to reverse the pattern of money loss was to go after the college market more aggressively and specifically with that consumer sector's needs in mind.

First, he simplified the menu, jettisoning sandwiches in favor of selling just pizza. And because Domino's was primarily a pizza delivery operation, Monaghan honed in on that, emphasizing fast delivery of pizzas that would also arrive hot. Monaghan developed the modern pizza box, a simple concoction of folded cardboard that could keep the pizza inside warm and fresh without collapsing under the weight of multiple other occupied pizza boxes, preventing cheese from sticking to the inside of the lid.

Domino sued Domino's

Domino's sells food, but it gets its name from something not edible — a dot-covered rectangle used in numerous tabletop games. It's not even the only food company to name itself after the domino, with Domino Sugar opening for business in 1901, about six decades before the similarly named pizza chain did. In 1947, according to Justia, the Amstar Corporation acquired Domino Sugar and helped build it into a sweetener industry leader. In 1971, Amstar lawyers wrote to Domino's, asking the pizza company to change its name. Domino's didn't respond to the letter and didn't change its name, and instead received trademark protection for "Domino's Pizza" from the U.S. Patent Office.

In 1975, Amstar and Domino Sugar sued Domino's Pizza, alleging trademark infringement and unfair competition by the pizza company and its franchisees, because they controlled the Domino name in the food sector. After five years of court battles, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled in favor of Domino's Pizza in 1980, allowing both companies to continue doing business under similar names.

Domino's embraced and then avoided the Noid

Fast food characters are numerous, but pizza chain mascots are few and far between. That was especially true in the mid-1980s, when Domino's hired advertising agency Group 243 to develop one for them, according to Fast Company. The ad wizards created a hit with the Noid —a bug-eyed, long-eared, nonsense-spewing, goblin-like creature in a red spandex outfit (clay-animated by the California Raisins progenitors at Will Vinton Studios) whose sole purpose was to be an agent of chaos, stopping Domino's drivers from delivering their pizzas in a timely fashion.

An odd, sinister, and even creepy mascot, Domino's customers and viewers of numerous Noid-based TV ads were urged to be careful with their pizzas (Domino's were "Noid-proof"), and to "avoid the Noid." But nobody was really scared of the Noid — shortly after his launch in 1986, he starred in two video games and inspired a briskly-selling line of merchandise.

According to Priceonomics, the Noid campaign came to an abrupt end in 1989 following a troubling incident involving a mentally ill individual. During a five-hour ordeal, a 22-year-old man held two employees hostage at an Atlanta Domino's, demanding pizzas and asking police for a large sum of cash and a getaway car. After police opened fire, they arrested the man, named Kenneth Lamar Noid, a man diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia who believed that the Noid ads were made specifically to tease him.

When Domino's went international

The Domino's organization celebrated three major and expansive milestones in 1983. That year, the chain opened its 1,000th pizzeria in the United States (and within two years after that, it could boast more than 2,500 stores). In 1983, Domino's waded into international territory for the first time, opening its first restaurant outside of the United States in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. Within that same calendar year, Domino's moved outside of the North American continent, launching Australian operations with an outlet in Springwood, in the state of Queensland.

By the end of the 1980s, Domino's had opened 5,000 locations in all, with several hundred of those in countries outside the U.S. International growth wasn't as quick or as easy as the domestic expansion Domino's had enjoyed. In 1986, according to Zippia, Domino's sold $16 million worth of pizza overseas, a meager portion of its overall sales figures. The company's most significant success outside of the U.S. came in India. According to Reuters, India is Domino's second biggest market and the company controls more than 70 percent of pizza sales there, operating more as a sit-down restaurant than a delivery-oriented business.

The most disastrous international expansion for Domino's, according to The Guardian, occurred in Italy. In 2022, the franchiser who ran all 29 of Domino's outlets in that country, the ancestral homeland of pizza, filed for bankruptcy when it couldn't compete with more traditional pizza places.

Domino's didn't alter its menu until the late '80s

After its very early flirtation with sandwiches, Domino's stuck with an extraordinarily simple menu for nearly three decades. They sold only pizza, and just two sizes and with a single crust style at that. In 1989, well after it had opened more than 2,800 stores, Domino's unveiled its first ever new product: thick-crust, or pan pizza. That began a period of relatively rapid menu changes and offerings for Domino's, bringing foods that weren't pizza back to the menu for the first time since its early search for brand identity. In 1992, Domino's introduced side items in the form of breadsticks, followed by a thin crust option on its pizzas in 1993, meaning customers could now order pizza in skinny, medium, and thick levels of crust depth.

Buffalo wings flew onto the Domino's menu in 1994, and in 2008, for the first time in more than 40 years, sandwiches returned to Domino's, this time oven baked. According to QSR Magazine, anyone named Jared (as in the name of Subway's pitchman) could get one for free. Those successful, permanent items were followed closely by pasta dishes and chocolate cakes.

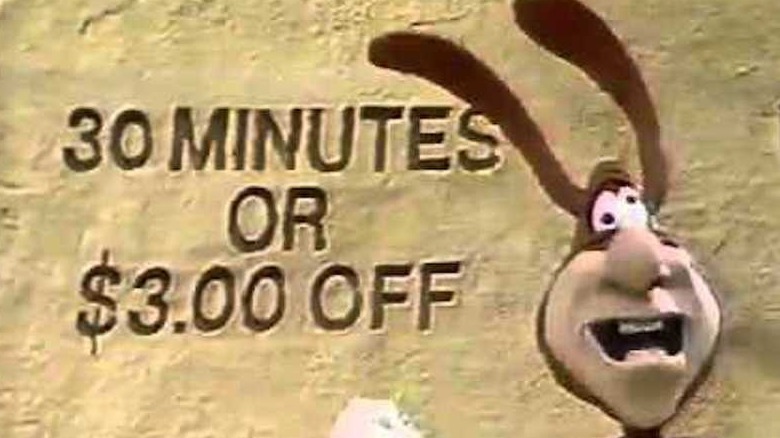

The '30 minutes or it's free' guarantee came at a tremendous cost

The number of Domino's stores reached into the multi-thousands in the 1980s, an explosive rate of growth fueled in part by an audacious marketing campaign. In 1979, according to The Washington Post, Domino's differentiated itself from other pizza places that delivered by guaranteeing that an order would arrive at the consumer's home within a half hour of placing it — 30 minutes, or it's free, in other words. The idea quickly entrenched itself in pop culture; in the 1990 "Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles" movie, the pizza-loving heroes count down the seconds until the "pizza dude" arrives, hoping for a free pie. There's also the 2011 pizza delivery-themed action comedy straight-up titled "30 Minutes or Less."

The offer lasted for about a decade, with Domino's changing the deal to a $3 refund for late pizzas, and then doing away with it for corporate-owned stores entirely in 1993. The reason: The promise was a threat to public safety. According to the AFL-CIO labor union, rushing Domino's drivers were involved in more than 300 car accidents. "There continues to be a perception that the guarantee is unsafe. We got that message loud and clear," Domino's president Tom Monaghan said when the guarantee was discontinued. That decision came on the heels of a $79 million lawsuit which Domino's lost, filed by a woman in St. Louis injured when a Domino's driver hit her car.

Domino's devised lots of ways to order a pizza

For decades, there were two ways of obtaining a freshly-made pizza. A customer could walk into a pizza joint, ask for a slice or order a full pie, and wait. Or they could call up the pizza place down the street, tell the person who answered the phone what kind of pie they wanted, and then go pick it up or pay a couple extra bucks to get it delivered. Domino's concentrated on the delivery model, and has introduced all kinds of high-tech and cutting-edge ways to order pizza that don't require walking or making a phone call.

In 2007, the same year that the iPhone launched and brought the internet out of buildings and into the pockets of millions, Domino's introduced ordering via its website. A year later, Domino's pioneered "Tracker" technology, a real-time order monitor that let customers know exactly when their pizza was being prepped, when it went into the oven, and when it was ready to collect.

Expanding on the idea, some Domino's locations even installed webcams so customers could also see their pizzas being made, according to Fast Company. In 2015, the Domino's Anyware program launched, enabling a variety of tech-based ordering opportunities via Alexa-enabled devices, Slack, Twitter, and Facebook Messenger. And there's even pizza AI — Domino's employs a Dom, an "ordering assistant bot" that can carry on text-based conversations with customers and help them get their pizzas.

Domino's fought hard against displaying calorie counts

The Affordable Care Act (aka "Obamacare," as it was among the signature legislative achievements in the administration of President Barack Obama) included a food labeling provision. According to Pizza Marketplace, it required restaurants with at least 20 outlets to list calorie counts of their fare on menu boards. The National Restaurant Association backed the law, but per The Washington Post, many chains remained adamantly opposed — primarily pizza places, who banded to gather to protest and fight. Domino's led the charge, with CEO J. Patrick Doyle publishing an open letter asking lawmakers to rethink labeling, claiming it cost too much and would prove too complicated for restaurants to implement.

Domino's then helped form an organization called the American Pizza Community to lead the anti-labeling crusade, joined by competitors Little Caesars and Papa John's and representing about 20,000 pizzerias altogether. The APC tried to get an alternative bill passed, the Common Sense Nutrition Disclosure Act, which would've dictated that massive pizza chains who do more than 50 percent of their business via phone or online ordering wouldn't have to post calorie counts in-store, and could publish the counts for individual servings rather than total orders. Nevertheless, the original law passed and went into effect in 2017, requiring Domino's to publish its calorie counts.

To celebrate 50 years, Domino's changed everything

Well-established brands with iconic products generally don't change up the recipe, preferring to stick to the old adage, "If it ain't broke, don't fix it." But as Domino's approached its 50th anniversary, the company had to do something, and it had to do something drastic if it wanted to survive in the competitive pizza marketplace. After a video of Domino's employees egregiously mishandling food went viral in 2009 (via The New York Times) and a Brand Keys consumer research project (via Unincorporated) ranked Domino's in last place among national pizza chains, the company self-rebooted. Domino's announced that big changes were ahead with a short documentary titled "Pizza Turnaround," highlighting very real and very brutal criticism of its products before CEO Patrick Doyle appears, commenting, "There comes a time to make a change."

Central to the new and improved Domino's were brand new building blocks of pizza. According to a press release, the crust would be garlic seasoned and come with parsley baked in, the tomato sauce would be more robust, with sweeter and spicier notes, and the cheese would consist of mostly real mozzarella with provolone mixed in. Having apparently been working on new ingredients even before the scandals of 2009, Domino's test kitchens spent two years developing the perfect new crust, sauce, and cheeses, testing 50 crust blends, 15 sauce concoctions, and more than 20 cheese mixtures. The finalists were picked from taste tests conducted specifically with people who had given up on Domino's years earlier.

Domino's delivers tech along with the pizza

Domino's has always been a delivery-focused pizza business, and in the summer of 2017 it tested a whole new and very futuristic way to get the pizza to the people. Domino's corporate headquarters is situated in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and that's where it tested a fleet of self-driving delivery vehicles. In a partnership Ford, area customers could opt to get their pizza via a Ford Fusion Hybrid Autonomous Research Vehicle, enabled with technology that sent a code to unlock the vehicle upon its arrival to retrieve the correct pizza from a heated compartment inside.

According to CNBC, Domino's rolled out e-bikes for use at stores in Miami, Salt Lake City, Houston, and Baltimore in 2019. In 2022, the company partnered with Chevrolet to introduce 800 Chevy Bolt electric delivery vehicles, part of a plan to become a zero-carbon emissions company by 2050 (via CNBC). That's an expansion on another venture between Domino's and General Motors, the DXP, a custom and purpose-built Chevrolet with special compartments to keep pizza hot and sodas safe. But Domino's isn't limiting itself to ground travel. Since 2016, according to Drone DJ, Domino's has been hard at work with SkyDrop to perfect pizza delivery drones for its stores in New Zealand.