The Daily Meal Hall Of Fame: Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

With the help of The Daily Meal Council, we have selected ten key figures in the history of food to honor this year in our Hall of Fame. Here, New York-based journalist, author, and Council member Jenifer Lang explains why Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, the author of a gourmand's bible published in 1825, belongs on the roster.

When I was attending the Culinary Institute of America, I overheard two students in the school bookstore who were inspecting a copy of The Physiology of Taste. One said to the other, "Who is this Brillat-Savarin guy, anyway?" The second student replied, "I don't know — some gourmet priest or something." Close enough. But he wasn't a priest, nor would he have called himself a "gourmet," but, rather, a "gourmand" (without the modern-day tinge of irony).

What these two students didn't realize is that without Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin they might not have been studying to become chefs in the late 20th century; more likely, they would be training to be electricians or automotive technicians. For there is a direct line from Brillat-Savarin's seminal book, published in France in 1825, to the inexorable era of culinary fascination that we are living in today.

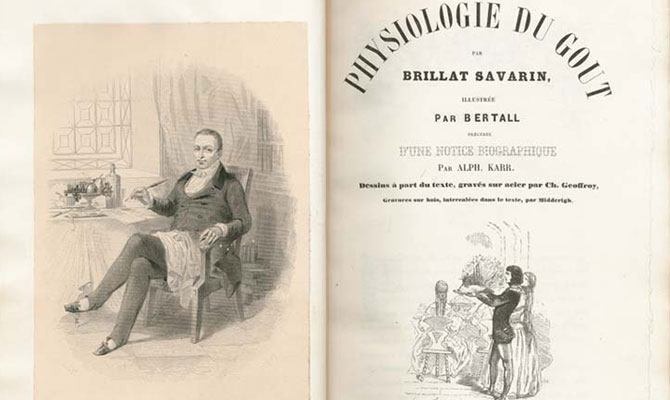

Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin (1755–1826) was a lawyer and civil servant, born in the countryside of France. He was professionally successful, but his enormous contribution to the ages was a book ponderously called Physiologie du Goût, ou Méditations de Gastronomie Transcendante, known in English as The Physiology of Taste, or, Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy. [pullquote:left]

It took Brillat-Savarin 25 years to write this book, although he confessed that he envisioned the work as a whole from the beginning, and the quarter century was needed simply to put the words on paper. It is the effort of a prodigious scholar whose obsession was food and drink and the analysis of myriad aspects of those subjects. If that sounds dry, then it is misleading, because, rather than a boring textbook, the work is an effervescent and charming autobiography that imparts knowledge as deliciously as if it were offering the most delectable cream-filled pastry.

When Brillat-Savarin finished his masterpiece and submitted it to publishers, he was not daunted by the fact that it was roundly rejected. He paid for the publication himself, and was vindicated when it was an instant success. In fact, The Physiology of Taste has never been out of print.

The beginning of the idiosyncratic book is titled "Aphorisms of the Professor," and many of these aphorisms are indelible: "Tell me what you eat, and I shall tell you what you are" (adopted as a slogan by Iron Chef); or funny: "A dinner without cheese is like a beautiful woman with only one eye." The rest of the unsystematic book ranges from analytical descriptions of digestion and cooking to recipes to dicta on social intercourse. There are generous helpings of stories from Brillat-Savarin's life; some told to illustrate a scientific point, some to further a personal theory about food, and some with little reason except to entertain the reader.

Reading Brillat-Savarin is like having the fortune to sit next to the best-looking, most entertaining, and funniest person at a party. His only goal is to make sure you have a wonderful evening — oh, and if you are lucky, he'll also want to seduce you once the evening is over. Brillat-Savarin was so fond of women that he never married. A monogamous relationship would have interfered with his love life! (He even counted physical desire as the sixth sense.)

The reason the book has never been out of print, and what makes it so important to our culinary lives today, is that Brillat-Savarin gave all succeeding generations permission to focus on food from all angles. His documentation elevated the study of food to an important place in his world — and in our world, too. Balzac said of the author: "He makes us feel smarter."

Brillat-Savarin lived when the Western culinary world was in a profound transition. Within his lifetime restaurants, as we know them today, were invented. Chefs became important to the world at large — not just to aristocrats. Haute cuisine was codified. Foodstuffs became more varied and plentiful. The West went from feeding itself to taking hedonistic pleasure in food. This transition mirrors the one our society has gone through in recent past decades, and we' still look to Brillat-Savarin for permission to take food as seriously as any other scholarly pursuit, as if being blessed by the high priest of all things culinary.

The Physiology of Taste is the gourmand bible; every bedside table should have a copy.