Food Labels, Decoded Slideshow

According to the USDA, "Organic is a labeling term that indicates that the food or other agricultural product has been produced through approved methods that integrate cultural, biological, and mechanical practices that foster cycling of resources, promote ecological balance, and conserve biodiversity. Synthetic fertilizers, sewage sludge, irradiation, and genetic engineering may not be used." Sounds great, except that the USDA affixes its "USDA Organic" seal to products that aren't completely organic — if its content is "95 percent or more organic," it's good enough for the USDA. Just something to keep in mind.

2. Biodynamic

Is biodynamic the new organic? It's not a term that has started popping up in grocery stores yet, but it may not be long before that happens. What often starts out as a "specialty" movement or product in farmers markets usually trickles down to brick-and-mortar stores — think of rocket, grass-fed beef, and pastured eggs. Such may be the case with biodynamically grown food. But how is it "better" than organic? Demeter USA, which performs biodynamic certification for farmers, created guidelines that go beyond organic calling for the inclusion of animals and crops on the same farm in a mutually beneficial relationship, requiring poultry to actually be raised outdoors, and promoting diversity over monoculture. These guidelines are based on the work of Dr. Rudolf Steiner, scientist, philosopher, and founder of the Waldorf school, who taught a series of classes in 1924 to farmers hoping to reverse the declining state of their farms.

To read more about biodynamic principles, click here to see The "New" Organic: Biodynamic.

3. Cage-Free/Free-Range

The USDA officially defines "cage-free" in the following manner: "This label indicates that the flock was able to freely roam a building, room, or enclosed area with unlimited access to food and fresh water during their production cycle." Their definition of "free-range" is similar but includes a stipulation that they have "continuous access to the outdoors during their production cycle." But prominent food writers such as Jonathan Safran Foer, author of Eating Animals, and Michael Pollan, assert that it's not quite as good (or meaningful) as it sounds. In their observation of chicken farms, for example, they note that "cage-free" chickens are often kept in sheds with tens of thousands of other chickens, uncaged, of course, and that "free-range" chickens are kept in similarly crowded sheds with a door at the end of the hall that leads out to a tiny dirt patch, which is kept closed for most of the chickens short life. So much for continuous access. Foer sums it up neatly and eloquently: "I could keep a flock of hens under my sink and call them free-range."

4. Pasture-Raised

The USDA doesn't have an official definition for "pasture-raised" yet, but we spoke to a farmer at the Union Square Greenmarket who sells eggs from pastured hens. Jon, of Millport Dairy located in Lancaster, Pa., says that his laying hens have access to the outdoors year-round, as long as weather permits. They have a steady and diverse diet of different types of grass, various insects, and wheat, resulting in a better-tasting egg. It seems like a loaded term at first, in the sense that farmers might have slightly different practices, but if you actually walk up and talk to them, they keep it pretty simple. It's only loaded when you don't ask questions.

5. Not Treated with rbST

Recombinant bovine somatotropin (rbST), also known as rBGH (recombinant bovine growth hormone) doesn't sound like something that would become a household name, but it has. And it is synonymous with "no thanks." It's a synthetic version of a hormone that's already produced by cows, known also as Posilac, which was developed in 1987 by Monsanto in order to increase milk production. Following their approval of the drug's use in 1993, the FDA has insisted that there is no "material difference" between the milk from cows treated with rbST and milk from those not treated. However, a 2010 court case in Ohio, International Dairy Foods Association v. Boggs, did in fact find a "material difference" — namely, that milk from rbST-treated cows exhibited increased levels of the hormone IGF-1, potentially lower nutritional value, and reduced shelf life. Thus, in the face of consumer demand, even large food product manufacturers and distributors such as General Mills, Dannon, and Walmart have moved toward phasing out rbST-treated dairy products.

6. "Natural"

The USDA actually has an official definition for "natural," but it only applies to meat, poultry, and egg products. It states that any such products "must be minimally processed and contain no artificial ingredients or added color." Minimally processed? What does that mean? That's pretty vague and doesn't really tell consumers a whole lot. Furthermore, if you see this term on anything besides meat, poultry, or egg products, it's hard to say if it means anything at all. At face value, buying something "natural" sure does sound good — but things like opium are "natural," too.

7. Antibiotic-Free

It's understandable that many consumers these days are concerned with antibiotics making their way into animal feed, and eventually, through the consumption of meat from such animals, into our bodies. Jonathan Safran Foer states that 3 million pounds of antibiotics are already administered to Americans each year; add to that another 17.8 million to 24.6 million pounds administered to livestock for nontherapeutic reasons, depending on whether you ask the meat industry or third-party sources. Furthermore, the American Medical Association, Centers for Disease Control, and World Health Organization assert that such practices are correlated with a proliferation of antibiotic-resistant pathogens. That being said, the USDA has prohibited the use of the term "antibiotic-free" on meat products, but allows "raised without antibiotics" and "no antibiotics." However, their requirements for issuing a "no antibiotics" label aren't exactly stringent. It applies only to meat and poultry, and is kosher to use as long as "sufficient documentation is provided to the Agency." Sufficient documentation. Not exactly reassuring. Still, "big players" such as Walmart, Hyatt Hotels, and Chipotle have jumped on the bandwagon anyway, hoping to capitalize on consumer concerns.

8. MSC Certified

You may have seen these blue labels on your last trip to the seafood counter. But what do they mean? MSC stands for "Marine Stewardship Council," an organization created by the World Wildlife Fund and Unilever to oversee the wild fish stocks around the world. In theory, fish that are MSC Certified come from fisheries that meet the organization's environmental and legal standards and are traceable from boat to fork. The organization is not without its problems, however.

To read more about what MSC Certified really means, click here to see Why MSC Certified Isn't That Meaningful.

9. Kosher

According to the USDA, when it comes to meat and poultry products, the word "kosher" can solely be displayed on products "prepared under rabbinical supervision."

In practice, consumers will also find various symbols on other food products. These symbols represent different kosher certification organizations, each of which charge a fee to manufacturers to use their symbol. Commonly displayed symbols include a "circle-U," "circle-K," "star-K," and "partially enclosed K," which represent OU, OK, Star-K, and Kof-K, respectively. These symbols are trademarked and cannot be used without prior approval. The organizations vary in how strictly they interpret traditional Jewish dietary laws, with OU being one of the strictest.

Beware, however, some food manufacturers also just use the letter "K" to assert that their food product is "kosher" even though it may not actually be the case. Jell-O is a notable example. This is because the letter "K" is not trademarked and therefore can be used freely. On the other hand, sometimes rabbis will examine and approve products but do not have permission to use a trademarked symbol, and so simply use the letter "K."

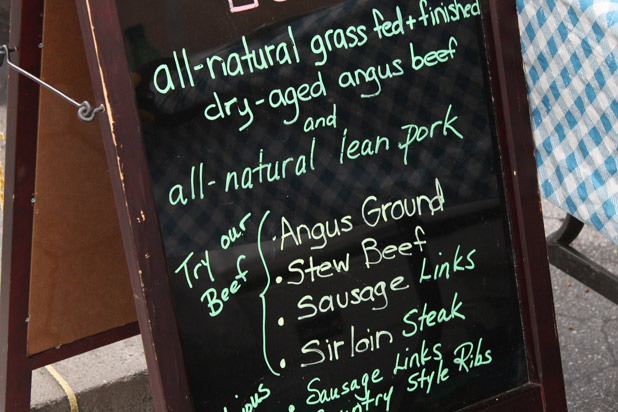

10. Grass-Fed

The USDA's official definition of grass-fed states, "Grass-fed animals receive a majority of their nutrients from grass throughout their life." That's a lot like their "USDA Organic" label, which basically says that 95 percent of the way is good enough. Furthermore, the USDA definition states that "the grass-fed label does not limit the use of antibiotics, hormones, or pesticides" in the animals feed. It is, therefore, not the end-all, be-all meat label that people probably hope for, and may believe it is.

Click here to see What's the Deal with Grass-Fed Beef?

Interestingly, according to Michael Pollan, even cows that aren't designated "grass-fed" often start out eating grass; it's later that they are finished on corn to promote marbling and create a product with a flavor closer to what consumers are accustomed to and expect.

11. Wagyu

Wagyu is a term more likely to be encountered in restaurants than in grocery stores, but the term is so confusing, we thought we'd include it on this list just to clear things up. Wagyu beef is desirable for its unique marbling, flavor, and texture, and as a result, it carries a hefty premium. According to the American Wagyu Association, Wagyu literally translated means "Japanese cattle." In practice, it refers to several breeds of cattle from Japan which have by now have been crossbred with various British and domestic breeds, including Angus and Hereford. Wagyu beef is not the same thing as Kobe beef, which can only come from Wagyu cattle raised in the Hyogo Prefecture in Japan. It's all very confusing, which is why the USDA has attempted to sort things out by prohibiting the use of the term "Kobe beef" here in the United States. It is acceptable to refer to beef from Wagyu cattle raised in the U.S. as "American-grown Wagyu beef" or "American-style Wagyu beef," but not as "Kobe beef," a term reserved for actual Kobe beef imported from Japan — which is now prohibited from being imported.

12. Fair Trade Certified

Consumers will find this label on a variety of products, not just coffee. It is found on tea, cocoa, fruits, vegetables, herbs, spices, sugar, honey, wine, and grains, as well as non-foodstuffs such as flowers and rubber products. Despite the (somewhat) tacky informational video on their site, the organization that issues the certification, Transfair USA, does seem to be on the level. Farmers in the program receive a premium for their goods that is used to improve the communities they live in. They must be organized either as a co-op or a union, refrain from using child labor, and refrain from using the top 12 most harmful pesticides. Most importantly, they are given access to financial capital which can help them compete in the global marketplace more effectively. Buyers who are Fair Trade Certified are also required to pay up to 60 percent upfront for certain commodities.

13. Pesticide-Free

The use of this term isn't regulated, and it's most often seen at farmers markets. Pesticide-free could mean just that — pesticides were not used in the production of a crop. But, the most important thing to take away is that it's not necessarily synonymous with "organic." There are other aspects to being certified organic, such as the prohibition against using GMO's, which may not be observed by "pesticide-free" producers. Then again, there are also small farmers who cannot or do not want to go through the organic certification process, but may be in compliance with the tenets of organic farming, and still want to communicate that they are farming in a responsible manner so they advertise that they are "pesticide-free." When you see this sign, it's probably best to talk to the producer just to find out what the story is.

14. DO/AOC/DOC/PDO

If you've ever seen products like "Parmesan Reggiano" at Trader Joe's, that's probably thanks to the protective power of one of these designations. They're typically found on European artisanal products and are basically a way of signifying an authentic product from a specific region or terroir, such as Parmigiano-Reggiano, prosciutto di Parma, or champagne. They're also a way of protecting the producers of such authentic products, ensuring a premium market price by preventing the name of the product from being used on imitations; hence, "Parmesan Reggiano" from Argentina. The different abbreviations are a result of European national government organizations that have each created their own system within their respective countries — in Portugal, there is the Denominación de Origen; in France, Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée; in Italy, the Denominazione di Origine Controllata; and in its attempt to unify various regulations and trade agreements, the EU has created the Protected Designation of Origin label. Chances are, if you see anything similar written on that bottle of wine or wedge of cheese, you're probably buying the real thing.

Click here to see the Arugula, Golden Cherries, Marcona Almonds, and Parmigiano Recipe.

15. Farm-Raised

This is a term that applies to fish; it's common to also see the term "aquaculture" these days. Farm-raised fish are commonly raised either in closed systems inland, or in open-net pens in the ocean. Farm-raised fish are subject to a number of problems, starting with their habitat. Those that are farmed in open-net pens often release tons of waste directly into the ocean. Many of the issues surrounding farmed fish stem from open systems — the disruption of gene pools in wild fish, due to breeding with escaped fish, and the destruction of native habitats, such as the removal of mangrove forests to farm shrimp in Thailand, are a result of open system farming.

However, both fish farmed in closed and open systems may have issues with overcrowding, and large fish (such as salmon) require a disproportionate amount of small fish (such as anchovies) for feed — the Monterey Bay Aquarium estimates it takes three pounds of small fish to yield a one-pound weight gain in salmon. Therefore, when purchasing farm-raised fish, it's important to find out what kind of system (open or closed) it was raised in, as well as the fishery's management practices.

16. Non-GMO

GMO stands for "genetically modified organism." For those concerned with the presence of genetically modified ingredients, components, or seed in their fruits, vegetables, and other food products, the current situation is a bit of a mess, but there are attempts to clean it up. An industry group called the Non-GMO Project conducts testing on existing products for various key companies, such as Whole Foods and Nature's Path. Their label indicates that a product contains no more than 0.9 percent of genetically modified material in its main ingredients. Not exactly great, but better than nothing, especially since the proliferation of genetically modified products has spread into the organic sector, a problem in the sense that such products cannot technically be called "organic" under USDA regulations. This is due to cross pollination from surrounding farms that use GMO crops. The majority of corn and soybean grown in the U.S., on which many food products are based, is genetically modified seed. Scientists maintain that GMO crops are safe.

18. Hothouse-Grown

A hothouse is essentially a heated greenhouse used to grow plants out of season. Common examples of hothouse-grown vegetables and fruits include rhubarb, tomatoes, and peppers. Results vary by crop — for tomatoes, it's pretty hard to beat the flavor and texture of a field-grown tomato picked at the height of ripeness from a farmers market, or even better, grown in your own backyard. Some people swear by hothouse-grown rhubarb, though when cooked, it holds its color and flavor better than field-grown rhubarb and is less stringy.

19. Sustainable

Here's a term that's used often by marketers and seldom defined. In the context of food production though, the simplest definition probably goes something like this: Food that has been produced or harvested in a "sustainable" manner minimizes environmental impact and takes into account resource and population management for the sake of future generations. But like many terms used for marketing, there is no official definition.

Click here to see Sustainable Fish Guide: The Best and Worst Fish.

20. Heritage Breed

In his book Eating Animals, Jonathan Safran Foer goes on at considerable length about the development (or downfall, if you agree with his perspective) of several animals that are central to meat-eating Americans: namely, chickens, pigs, and turkeys. To sum up a couple hundred pages of reading, basically, pigs have been bred into leaner animals (the "other white meat") that reproduce unnaturally quickly, while chickens and turkeys have been selected to grow faster on less feed, and in the case of layer hens, produce more eggs. All this has occurred to the detriment of their health and welfare and resulted in an almost mandatory use of antibiotics in their feed. These are animals that would not survive on their own in the wild past their usual dates of slaughter.

For consumers who already possess this knowledge but aren't ready to give up meat, a few producers have stepped in claiming the use of "heritage breeds" Pollo Buono, for example, in the case of chicken, D'Artagnan in the case of turkeys, and Flying Pigs Farm in the case of pork. These animals are supposed to come from stock predating most of todays factory-farmed animals, may lead better lives, and well, quite frankly, taste better. But the only way to make sure is to examine each producer on a case-by-case basis.

21. Artisanal

This isn't a legally regulated term either, and so it gets used a lot because it sounds good — when people think of artisanal, they're probably thinking of a passionate baker, slaving away over some hot hearth in the wee hours of the morning, making the same, perfect baguette that he does every morning. Someone French, probably. Or a grape grower, patiently culling his grapes to make sure only the best ones make it into the barrel. The dictionary definition implies that something artisanal is made by hand. If you believe in that as a starting point, adding the "food perspective" probably involves making something by hand, slowly, in small batches, and with great care, resulting in a superior product. In the olden days, the original sense of the term would have implied becoming an apprentice, then a journeyman in a craft, finally culminating in some sort of "masterpiece" that would result in ones status as an "artisan." So is that $30 piece of cheese behind the display counter a masterpiece? Well really, the only way to find out if an "artisanal" product is worth its weight in gold is to taste it.

22. Halal

Halal means "permitted" or "lawful" in Arabic. With respect to food, anything that is permitted under dietary guidelines outlined in the Quran is considered "halal." Here in the U.S., it is most commonly used to refer to meat. Halal meat must come from animals that are slaughtered in a humane manner; more specifically, the jugular vein must be cut with a sharp knife and all of the blood must be drained from the animal. This is because the Quran prohibits the consumption of animal blood, in addition to pork, pork products, and animals dead before slaughter.

23. Pareve

Pareve, also sometimes spelled "parve" or "parev," appears on kosher products and means that the product is "neutral" in the sense that it does not contain meat or dairy products, and can be served with either meat or dairy. This is useful for those who observe the restriction against consuming meat and dairy together.

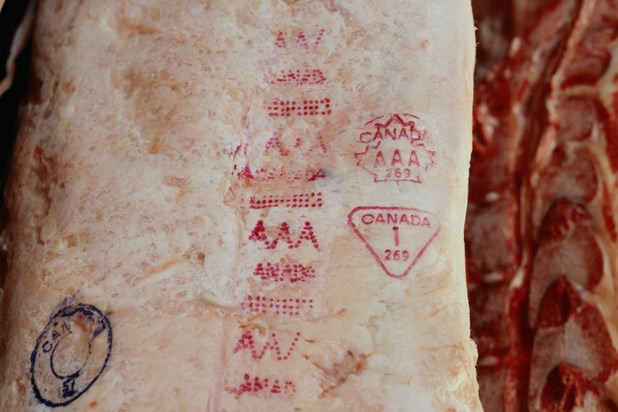

24. Meat Grading

The USDA runs two separate programs for grading — one is mandatory and the other voluntary. The mandatory program inspects for "wholesomeness," while the voluntary program is the one that most people are familiar with.

On beef, you will likely see one of three grades, based primarily on marbling, the fat found within the muscle. You will probably see USDA Select and Choice most often Choice has more marbling than Select. At the top end of the scale is Prime, most often seen in specialty retailers and restaurants. At the bottom end of the scale are USDA Standard, Cutter, and Canner, which are not usually seen in stores and used to make other products such as ground beef.

For poultry, you should only see Grade A meat in stores. Grade A simply means that "poultry products are virtually free from bruises, discolorations, and feathers. Bone-in products have no broken bones. For whole birds and parts with the skin on, there are no tears in the skin or exposed flesh that could dry out during cooking." Grades B and C are used in processed products.

25. Probiotic

Probiotics seem to be all the rage these days. Just walk down the dairy aisle in the supermarket and there are bound to be dozens of brands of yogurt all advertising the use of probiotics and perhaps some purported health benefits. Some claim improved immunity, while others claim better digestion. But do they really do any good? Experts say results will vary simply because there are so many strains of bacteria, each of which yield specific benefits, and many of which are untested. And your stomach's already full of probiotics anyway...

To read more about the debate, click here to see The Truth About Probiotics.

26. Certified Angus

Certified Angus Beef is a registered trademark and brand of beef that comes from Angus cattle. In order to be certified, the beef must fall in one of the USDA's top two grading tiers: USDA Choice or USDA Prime. There are other criteria considered, such as carcass weight, fat thickness, the size of the rib-eye, and some cosmetic considerations, but basically it boils down to marbling how much intramuscular fat is in the beef. Certified Angus Beef is purported to have superior marbling to non-branded beef.

17. Vine-Ripened

Honestly, this one is a bit of a shill, but you probably already suspected that. The question is, just how much of a shill is it? The term refers to tomatoes; vine-ripened tomatoes sound like they've been left on the vine until red ripe, but what it actually means in practice is that they were left on the vine just a bit longer than "non-vine-ripened" tomatoes, just long enough for the first sign of red to appear on a mostly still green tomato. Before the tomato reaches the store, a blast of ethylene gas (a type of gas naturally produced by ripening fruit such as bananas) turns all tomatoes red, regardless of whether they are vine-ripened or not, to convince people that they'll taste decent. Vine-ripened won't really taste any better, but the'll probably cost a good deal more.