The Tumultuous History Of Pumpkin Pie

Pumpkin – technically a fruit since it grows from a flower — originally hails from the Americas, where indigenous peoples boiled and baked it in many forms before it found its way across the Atlantic and into a pie crust. Baking pumpkin is a phenomenon that came full circle when European settlers brought their pie-making practices with them to the American colonies and borrowed from the natives' traditions of cooking squash to adapt pie recipes to the local flora.

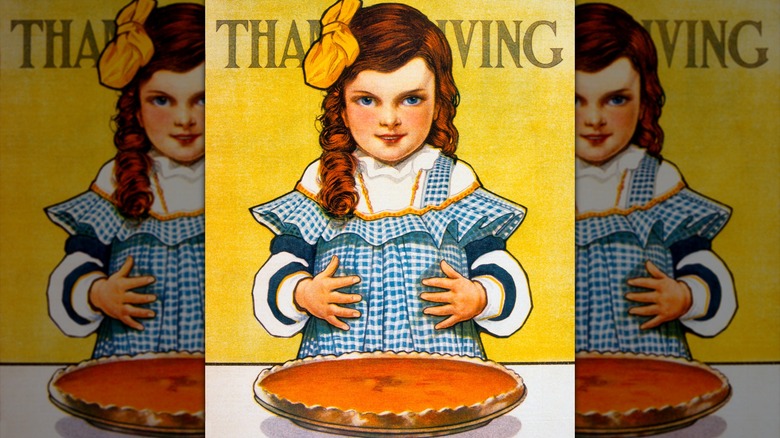

The pumpkin pie, today a humble holiday staple, wasn't always or immediately the pièce de resistance of a Thanksgiving meal. The pie's origins follow the history of transatlantic trade, and baking it wasn't something that caught on right away. Pumpkin pie was a difficult dish to prepare prior to the 20th century, and its taste was not preferred to other fruit pies that offered more vivid colors and flavors. In fact, pumpkin pie's eventual rise to popularity had less to do with the merits of its flavor and more to do with its political symbolism. In the 19th century, it came to represent abolition, rising from an obscure New England country dish to become a celebrated dessert lauded in poetry and propaganda.

Today the fraught origins of the pumpkin pie have congealed into a subtly-spiced dish that many anticipate now with a seasonal nostalgia. But there's a lot more to the history of this autumnal dessert that has contributed to giving pumpkin pie a place at the Thanksgiving table.

Pumpkin pie has Renaissance origins

The tradition of pie-making in northern Europe dates back to the Middle Ages, taking inspiration from the pastry-making practices of ancient Mediterranean civilizations. The pie we understand today as a pastry-encased filling was constructed as a means of convenient food preservation and transportation – the crust could be eaten along with its contents, but was largely intended to be a receptacle for what lay within. Until the 1500s, pies were predominantly savory. It was at the end of this century that fruit pies made an appearance.

Options for pie fillings expanded in the 16th century when Europe was introduced to many new crops through the Columbian Exchange. This phenomenon refers to the sharing of cultures, philosophies, and agricultural practices between the "new world" and the old during the Age of Exploration. Corn, tomatoes, peanuts, and pumpkins were among the new foods brought from the Americas that were gradually incorporated into European cuisine. While Europeans were wary of cooking with many of these unfamiliar foodstuffs, they were quick to invite the pumpkin into their culinary sphere. Pumpkins resembled the gourds and squashes that grew naturally in Europe, and besides being just as easy to cultivate, also had a better flavor. Pumpkin became a natural addition to European dishes, and eventually found its way into sweet and savory pies. England specifically adopted the pumpkin into its tradition of pie-making, but these Renaissance-era pumpkin pies were typically double-crusted, and filled with alternating layers of sliced pumpkin and apples.

The first pumpkin pie was French

While pumpkin found great success in diverse recipes across Renaissance England, the first recorded recipe of a pastry filled with pumpkin in a sweet flavor profile is from 17th-century France. The recipe comes from renowned French Chef François Pierre La Varenne, who is credited with modernizing French gastronomy, bridging the heavy spices that defined Medieval French cooking into an emphasis on simpler, regional flavors.

First published in 1651, Varenne's cookbook, Le Vrai Cuisinier Français (The True French Cook) is considered one of the founding texts of modern French cooking. It redefined the methodology of teaching French cuisine by transcending oral instruction to offer a written and accessible guide that could be consulted by anyone who could read it. Among the book's recipes is a recipe that resembles today's classic pumpkin pie. Called a tourte de citrouille (pumpkin tourte), the dessert was presented as an open-faced tart, with a rolled-out pastry filled with a mixture of pumpkin, milk, sugar, and butter, as well as a sprinkling of almonds, if desired.

Varenne's culinary guide emphasized the local cuisine. His inclusion of pumpkin amongst these recipes highlights that pumpkins, at the time, were ubiquitous enough throughout France to be integral to a definitive book of 17th-century French cooking, turning a pumpkin pie prototype into a more or less a traditional dish in the milieu of evolving French cuisine.

It wasn't initially a Thanksgiving hit

Though pumpkins were certainly known to both the Plymouth pilgrims and the Wampanoag who joined together to celebrate the first Thanksgiving in 1621, pumpkin pie was not a dish on the menu. It is likely that pumpkin was served during this feast in some form (it was a prevalent part of native agriculture), but the pilgrims did not have the technology to prepare pumpkin pie properly — the Plymouth colony lacked an oven for baking.

Once these pilgrims achieved baseline subsistence and could indulge in more elaborate cuisine, first-hand accounts suggest that even after they could bake pumpkin pie, settlers would not have preferred it anyway. As settlements in New England took root, the colonists who had likely consumed more than their fair share of pumpkins (due to their dependence on the local flora) developed a hankering for fruits from their homeland. Edward Johnson, a ship captain from Massachusetts, wrote in his 1654 book Wonder-Working Providence that a few decades after the first Thanksgiving, the members of thriving settlements wanted "apples, pears, and quince tarts instead of their former Pumpkin Pies."

Thanksgiving itself was a tradition that didn't catch on quickly amongst the American colonies. It didn't become a regular holiday until the 1700s, and then only in New England. A century later, resources such as 76, A Cook Book from 1876 would go on to refer to pumpkin pie as "New England Pumpkin Pie," reflecting a continued regional association with the dessert.

Early recipes prepared pumpkins in many forms

Pumpkin pie in its early days was initially a fairly nebulous concept — the title referred to any number of sweet or savory combinations that used pumpkin as the predominant ingredient. In Europe, many early recipes kept the trend of cooking pumpkin with apples, from filling a pie crust with a mixture of the two to simply stuffing a whole pumpkin with apples and cooking it that way. Anna Wooley's 1670 English cookbook Gentlewoman's Companion highlights this phenomenon of pumpkin and apple pie. Her recipe for "Pumpion-Pye" is distinctly filled with slices of fried pumpkin, and is seasoned with rosemary and thyme.

In the American colonies, ginger, nutmeg, and allspice were the more accessible seasonings to accompany a pumpkin pie. Many early New England pumpkin pies were glorified cooked pumpkins with no crust to speak of — it was not uncommon to fill a pumpkin with sweetened milk and roast it straight over a fire. It wasn't until 1796 that a mainstream American recipe appeared in the recognizable form of an open-faced pie with a custard-like pumpkin filling. This recipe is in Amelia Simmons' American Cookery, the first cookbook written by an American to be published in America. While Simmons includes a recipe for a Winter Squash Pudding mixed with apples distinguished as "a good receipt for Pompkins", she also includes two separate recipes for pompkin pudding, which combine stewed pumpkin with eggs, sugar, cream, and spices to be baked inside a crust.

In the 1800s, pumpkin pies were a political symbol

In Britain, pumpkin pie began to lose popularity in the 18th century, but in the Americas, this was the time when pumpkin pie would soon be on the rise. Since Thanksgiving's development into a regional tradition in New England, pumpkin pie had become a seasonal delicacy, though it was by no means mainstream. The humble dessert was popularized in the following century when it became a signifier of the political upheaval of the 1800s as a symbol of the abolition movement.

Pumpkins might seem like an unassuming emblem of anti-slavery, but there was a deep-rooted reasoning as to why they represented the abolitionist cause. Because pumpkins were a crop that grew easily and required very little labor for cultivation and harvest, pumpkin farming operated as the antithesis of the plantation economies of the South where cash crops like cotton, sugar, and tobacco were being mass-produced through exploitative slave labor.

Beyond boycotting plantation crops, supporting industries that had no slave labor in the economic equation was an even more overt means of supporting the anti-slavery movement. New England abolitionists popularized the pumpkin pie as edible propaganda, and this new favored dessert was specifically highlighted in anti-slavery literature of the period. Abolitionist writers Sarah Josepha Hale and Lydia Maria Child include odes to pumpkin pie in their respective works of fiction and poetry. The latter's famous poem "Over the River and Through the Wood", ends with the line, "Hurrah for the pumpkin-pie!"

Post Civil War, pumpkin was a divisive dessert

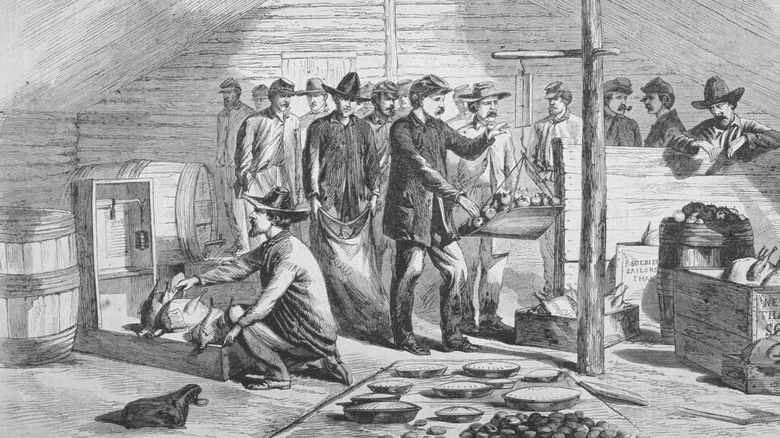

As the question of slavery brought America's North and South into the Civil War, the pumpkin pie and all it represented remained at the heart of this national conflict. When, in the midst of the war, President Abraham Lincoln declared Thanksgiving a national holiday in 1863, the decree sparked more division between regions, rather than the unity the holiday was supposed to represent. New England unionists embraced Thanksgiving with a newfound fervor, and the newly symbolic pumpkin pie took center stage as the traditional dessert for this holiday.

Confederates in the South, however, were reluctant to celebrate something in the middle of the war that had such deep ties to New England tradition. Regarding this new national holiday as a means of imposing northern values, many southern households refused to acknowledge, let alone celebrate Thanksgiving.

It wasn't until after the Civil War, during the period of Reconstruction, that Thanksgiving truly took root as a nationally celebrated national holiday. While southern states began to celebrate Thanksgiving, they remained firm in their resolve to boycott pumpkin pie. Even though pumpkins grew well and plentifully in the South, they were still vessels of anti-slavery symbolism and served as a reminder of who had lost. Many Southerners opted for sweet potato pie instead, perhaps neglecting to recognize that this dish has African roots. It was only in the 20th century that southern Thanksgiving tables finally began to include pumpkin pie as a dessert for the holiday feast.

Canned pumpkin made the pie more popular

One main reason behind the nationalization of pumpkin pie in the 20th century was the invention of canned, pre-cooked pumpkin, which the canning company Libby's introduced in 1929. This revolutionized pumpkin pie, first and foremost because it streamlined the baking process. While pumpkins may have been easy to grow, they were not easy to prepare. Prior to Libby's canned pumpkin, the methodology required to prepare a pumpkin for pie was time-consuming and labor-intensive. First, a pumpkin had to be skinned and gutted, then cooked for 6-8 hours before it was in any way ready to become pie filling.

Today, Libby's sells 90 million pies' worth of canned pumpkin every year, and the brand has changed the American perception of pumpkin pie through the recipe included on the back of its canned pumpkin. Introduced as early as 1934, Libby's pumpkin pie has since become so ubiquitous it has standardized our expectation for what a pumpkin pie is supposed to taste like. Made today from Dickinson pumpkins that hail from Illinois, the pumpkin in Libby's canned pumpkin has been selected for its superior texture and flavor. While recent recipe trends have revealed plenty of ingredients to upgrade pumpkin pie, the beauty of Libby's simplicity is that anyone can make it. Calling for easily accessible ingredients and a store-bought crust, Libby's pumpkin pie recipe is an easy-bake tradition in itself. But here's another easy pumpkin pie recipe, just in case you're tempted to try something new.