The Ultimate Foodie Guide To Eating In Québec

The second most populated province in Canada — and its only Francophone province — Québec has a rich history dating back to 1608 when early settlers from France began establishing a new colony along the St. Lawrence River. These early settlers were hearty, conservative people who lived modest lives. They brought recipes and food traditions (like cheesemaking) to the New World. These traditions, adapted to incorporate locally available Indigenous foods, have become the bedrock of Québécois cuisine.

Yet, its culinary evolution would not end there, transitioning through times of upheaval, including the British colonial period beginning in 1759 and becoming a part of Canada in 1867. Ingenuity paired with fierce loyalty to French heritage has allowed Québécois cuisine to take on more nuance, fusing immigrant traditions brought to Québec from across the globe with foods cultivated locally. Food in Québec is simultaneously modern and classic, edgy and traditional.

To visit Montréal or Québec City feels like walking into a European city, a trip back in time. And yet, so much of the food scene in the province is innovative. It is the best of all worlds — rendering Québec a food enthusiast's paradise. Let's look at some unique foods and beverages you cannot miss while visiting Québec.

Bagels

The bagel is perhaps the perfect representation of the melting pot responsible for the unique vibe of Québécois cuisine. Brought with Eastern European Jews who fled to Montréal in the early 1900s and settled into a northeastern neighborhood called Mile End, bagels in Québec enjoy an almost cult-like following. While nobody knows who introduced the first bagel, the debate rages between two factions: those who swear by the bagels from Fairmount Bagel and those who will only eat the ones from St. Viateur Bagel.

For those accustomed to the New York-style version of a bagel, don't expect the same thing from a Montréal bagel. These bagels have been made in the same way from the beginning. They're boiled in honey water, hand-rolled, and baked in a wood-fired oven, giving them a distinct taste and texture. Fashioned from malt flour and without salt or eggs, these bagels are denser, crunchier, and less fluffy than their New York counterparts. This simplicity lends itself to more substantial toppings, making these bagels hearty meals — something that is often said to reflect the personality of the people of Québec themselves as tough and resilient.

Crêpes

Crêpes are as central to the cuisine of Québec as they are to that of France. While some evidence points to 13th-century Brittany as the historical origin of the crêpe, these delicate, lithe pancakes have become synonymous with cultures across French-speaking nations. Like the crêpes found in France, crêpes in Québec are also typically made with buckwheat flour, although they tend to be slightly sturdier with delicately crunchy edges.

The classic French-Canadian crêpe is served either sweet, overflowing with fruit and whipped cream, or savory, stuffed with every possible permutation of fillings, from eggs and meat to locally sourced vegetables and cheeses. One of the more well-known crêperies, Casse-Crêpe Breton, is in Old Québec City, near the historic Fairmont Le Château Frontenac. It has served classic Québécois crêpes to tourists and locals for almost four decades. Newer, more niche boutique crêperies are popping up daily with updated options catering to those with dietary restrictions ranging from vegan to gluten-free.

Poutine

Few foods scream "Québec" the way that poutine does. This combination of french fries, cheese curds, and gravy has become the "casse-croûtes," or "greasy spoon," a favorite choice for Quebeckers. "Poutine" is a Québécois slang term for "mess," presumably referring to its slightly sloppy appearance. While nobody knows with certainty who invented the dish, the most common legend out there is that its current iteration was an amalgamation of two events.

First, in 1957, a customer at a restaurant in Warwick, Québec, requested that the owner put local cheese curds together with his fries to expedite things. Later, in 1964, gravy found its way into the mix to moisten the dish and keep it from getting cold too rapidly. The combination purportedly became so popular that it spread like wildfire across Québec and beyond.

In Montréal, for example, poutine can be found around virtually every corner, and new iterations with every imaginable topping are commonplace. We sampled the classic variation with just cheese curds and gravy. What set the French-Canadian version apart from any we have ever had in the U.S. was the texture of the fries, which were thin and crisp enough to resist getting soggy under the weight of the rich gravy. A bite of these magical gravy-soaked fries, paired with that quintessential squeak from cheese curds — is mouthwatering. Paired with a pint of a locally brewed beer, this is one of the more memorable experiences you can enjoy in Québec.

Tire sur la neige

Tire sur la neige, or maple syrup on snow, is a maple taffy that is concocted by heating pure maple syrup to precisely the right temperature so that when it gets poured onto clean snow, rather than melting the snow, it adheres to it, enabling you to swirl this unctuous maple syrup around a stick or spoon with the snow into a kind of popsicle. It is a delicacy best enjoyed from sugar shacks, or cabanes à sucre, throughout Québec. Early settlers learned how to make these treats from the Indigenous populations inhabiting the region when they arrived in the 1600s.

Québec has a long and tumultuous legacy as a premier maple syrup-producing region of North America and was even the site of a maple syrup heist in the early 2010s. Today Québec produces almost 75% of the world's maple syrup supply, with tours available in early spring of farms tapping their maple trees and harvesting the syrup. Like wine, maple syrup tends to reflect the terroir in which it originates. Everything from the climate and soil to the topography of an area can cause distinct variations in the flavor of the harvested syrup. And it takes 40 gallons of maple sap to create 1 gallon of maple syrup, making this quite a luxury in the region.

Local maple syrup can be made into innumerable edible and inedible products that make for great souvenirs to bring home. We particularly enjoyed the maple salt, maple butter, and maple candles we found in Old Québec City.

Couscous

Montréal is one of the largest Francophone cities in the world. Unsurprisingly, French-speaking immigrants from former French colonies of North Africa, like Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, have made their way to this cosmopolitan yet tradition-filled city. With these migrants come some of their most authentic foods, like the pasta made of durum semolina flour called couscous. These little pasta balls, typically formed by hand, are dried and then steamed in a couscousière, a double boiler in which a meat and vegetable stew filled with spices cooks in the base as the couscous delicately steams in the top.

While couscous with seven vegetables is a traditional meal generally served to large families on a Friday afternoon, it has become a popular dish in the predominantly hipster community surrounding the Plateau Mont-Royal area of Montréal. "Couscouseries," or couscous stands, have also popped up across the city, with numerous adaptations of this classic dish incorporating locally found game meats and vegetables.

Smoked meat

Montréal-style smoked meat, or "viande fumée," is a religious experience in Québec. The Office Québécois de la Langue Française officially designated "smoked meat" to refer to this delicacy, effectively canonizing it into the French-Canadian language and culture. Smoked meat in Montréal refers to the meat itself and the sandwich, which is always served the same way, on rye bread, with yellow mustard and a pickle. Its preparation involves liberally seasoning a beef brisket in a peppery dry rub, marinating it for 10 to 20 days, and then dry-smoking the meat for six to nine hours. This slow, laborious process sets the Montréal delicatessen experience apart from the New York one.

While the origins of Montréal-style smoked meat are ambiguous, what appears to be sure is that the method of cooking meat this way likely came from Turkey by way of the Ottoman Empire, was further refined by Romanian Jews, and eventually brought to Québec, where it began being sold by a butcher named Aaron Sanft in 1894. From that point on, smoked meat became ubiquitous in Montréal.

To this day, a long line forms daily of patrons eagerly awaiting the opportunity to dine in Montréal's oldest deli, Schwartz's Deli. It began serving smoked meat sandwiches in 1928 and is still going strong with the help of an unlikely patron saint, Céline Dion, who became part-owner of the institution in 2012, ensuring that it goes on and on.

Cheese

It certainly isn't shocking that a region whose settlers heralded from a country with such a rich, well-established cheese-making culture as France should bring those skills with them. Colonists of New France were integral in turning Québec into what is today considered one of the most prolific and sophisticated cheese-making cultures. The earliest cheese-making school established in North America was opened in the Québécois parish of Saint-Denis-de-Kamouraska in the 19th century.

Cheeses in Québec are diverse, taking advantage of locally sourced goat, sheep, and cow's milk. The distinct micro-climate of the region imposes unique flavors often described as sweet, fruity, and nutty while simultaneously demonstrating nuances that are distinctly redolent of the forest, including wild mushrooms. Some of the more popular cheeses of Québec include Doré-mi, Grey Owl, Belle Crème, Alfred le Fermier, Bleu l'Ermite, Brise du Matin, and Mamirolle.

A great way to experience the cheese culture of Québec is to visit the Eastern Townships region. Here you can follow a cheese trail known as Les Têtes Fromagères, also known as the Cheesemakers Circuit, which features 15 different cheesemongers.

Fèves au lard

Fèves au lard, or baked beans, are a frequent breakfast dish among Quebeckers. It is also a delicacy that is a staple at the many cabanes à sucre, or sugar shacks, that dot the region. What sets these beans apart from other baked beans is maple syrup. These slow-cooked beans with salt pork incorporate the signature sweet treat generously, paying homage to the importance of maple syrup to the culture and economy of Québec.

It may not be surprising that the modern-day recipe likely evolved in the 19th century from interactions between the people of Québec with those of New England, specifically Bostonians. However, the legacy of cooking beans with maple syrup and animal fat can get traced farther back to the Indigenous people who inhabited the area before settlers from France arrived. These beans were slow-cooked in earthenware pots set over hot stones for a delicious and healthy meal.

While fèves au lard are less common in the increasingly cosmopolitan society of Montréal, many restaurants still specialize in this French-Canadian comfort food. Try it as a side dish with a hearty breakfast of smoked meat, eggs, and toast. This breakfast will fuel your day of walking the hilly streets of Montréal.

Tassot

The history of Haitians migrating to Québec is lengthy. It began in the 1960s and 1970s during the dictatorship of Francois Duvalier. At this juncture, thousands of Haitians arrived in Montréal, hoping to find refuge in a Francophone nation. Their arrival coincided with an economic, political, and cultural revolution in Québec called the Quiet Revolution. During this era, women achieved gender equality, electricity became nationalized, and the University of Québec was founded. Since that period, Haitians have seen ups and downs in their struggles with racial equality, but their place within the cultural heritage of Québec has remained seminal. Indeed, there are approximately 140,000 Quebeckers of Haitian descent living there today.

Certainly, Haitian immigrants brought with them their culinary traditions, which have become popular and embraced within Québec. One of the most well-known Haitian dishes, tassot, is a stew made of goat meat or beef that has been brined in onions, lime, and orange juice and then fried to crispy perfection. This dish gets served alongside fried plantains, rice, beans, and a condiment known as ti malice, a hot sauce made of scotch bonnet peppers. Many Haitian restaurants in the neighborhood of Montréal known as Little Haiti serve delectable variations on the classic tassot. This neighborhood is rich in culture and worth a visit for the food alone.

Creton

Creton is a French-Canadian variation on a classic French rillette — a pork paté combined with onions, garlic, bread crumbs, and spices like allspice, cinnamon, ginger, and cloves. This forcemeat is often served on toast for breakfast, as an appetizer smear on croutons, or as a spread on a hearty sandwich. Early creton likely evolved from similar recipes eaten by Indigenous inhabitants of the region. It became popularized by monks in monasteries dotting the St. Lawrence River. This recipe often used meat sourced from pork ribs that were salted and roasted.

For the uninitiated who have never partaken of a classic rillette or any other type of paté, the texture and flavor of creton may be slightly foreign. Indeed, it is a bit of an acquired taste among Quebeckers. To help tame the minerally and slightly grainy spread, pair it with a hint of sweetness from maple butter or apple butter. A perfect beverage to cut the richness of creton is something bubbly, like a local microbrew or a glass of sparkling wine.

Pâté chinois

Pâté chinois, or Chinese pie, is a dish reminiscent of a British Cottage pie or Irish Shepherd's pie, containing ground beef, canned or fresh corn, and mashed potatoes. Its origins have been the topic of great controversy. Some insist that the pie was assimilated from its British counterpart during the colonial period by Chinese rail workers tasked with building the Canadian railway. Others insist that it has some history linking to the New England town of China, Maine, during World War I, when persecution of French-Canadians in the region was common. This racist and sordid story linking anti-Chinese xenophobia to anti-Québécois sentiment is told in a book by a professor of sociology at the Université du Québec à Montréal, Jean-Pierre Lemasson, titled "The Inscrutable Mystery of Pâté Chinois." However, as Lemasson himself noted when interviewed for WBUR's podcast "Last Seen," pâté chinois' precise origin remains uncertain.

Wherever the dish came from, it is considered the unofficial national dish of Québec. It utilizes ingredients traced back to the Indigenous civilizations of the region, including corn, a staple of these early civilizations. Pâté chinois is a rustic dish commonly made at home or served in cafeterias throughout Québec with a side of ketchup.

Soupe au pois

Soupe au pois cassé is a split pea soup often called "habitant soup." It is a rich delicacy that hearkens back to the original settlers of New France, or "habitants," in the early 1600s. According to historians, the ingredients most commonly found in this soup were staples aboard the ships of Samuel de Champlain. These ships would get stocked with foods with long shelf lives, including vinegar, honey, cheese, rice, legumes, and dried, salted meats and fish. Of these humble ingredients, full meals got fashioned to keep the early settlers fueled during the long voyage.

Once these settlers made homes along the St. Lawrence River, they quickly adopted locally available ingredients. They also began farming pigs, fruits, vegetables, and legumes. Early variations of this soup were likely a pared-down version made with salted ham, peas, and vegetables. The soup quickly evolved to include game meats and other, more exotic permutations with rich broths giving the soup a stick-to-your-ribs heartiness invaluable to those trying to survive the harsh Canadian winters with limited resources.

Today the soup is often served in cabanes à sucre on Fridays. The soup always gets eaten with a chunk of crunchy bread — something no meal would be complete without. It has become so popular that instant and canned versions of this soup are available across Canada.

Tourtière

Tourtière, or meat pie, is one of the most quintessentially Québécois of all foods — perfectly encapsulating the history, culture, tradition, and location from which it evolved. It is a dish dating back to the early settlers of New France, which likely was based upon a variation known as cipaille, or "sea pie," a British meat pie. The most famous version is associated with the Saguenay Lac-St-Jean region of Québec, but tourtière can be found throughout the province.

Original recipes were fashioned from chopped meats, including pheasant, rabbit, moose, and pigeon. Today, it is most frequently made using ground pork and beef, tucked delicately into a dual-pastry crust. Its unusually festive seasonings speak to the legacy of eating this pie on Christmas Eve as part of the meal served after Midnight Mass, or Réveillon. These spices include cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, and allspice, making tourtière a delightful amalgamation of sweet and savory.

While precise ingredients are adaptable, what never changes is that this is a dish to be enjoyed by families as part of a celebratory meal. It always gets paired with a homemade condiment reminiscent of chunky green ketchup or good old Heinz ketchup. Regardless of the accompaniment, what matters is the tradition behind the dish.

Tarte au sucre

Tarte au sucre, or sugar pie, is another relic of the early settlers of New France. These natives of France brought a variation of this pie with them, quickly adapting it to incorporate local ingredients, chief among them maple syrup. These were rugged, humble folk who cooked quickly and easily prepared foods, taking advantage of what they could forage or grow, including pork, which provided the lard used for the delicate pie crust. While most modern variations use brown sugar, some cabanes à sucre still serve the authentic maple version.

If tarte au sucre looks somewhat familiar, that is because permutations of this recipe made their way from Québec into the U.S. It is similar to both an Amish shoofly pie and a classic Louisiana pecan pie. Its flavor, despite its name, is not as sweet as one might think. Some have equated it to having the burnt caramel flavor reminiscent of a crème brûlée. Regardless of the variation of tarte au sucre, it's a dish best enjoyed after a long day out in the cold, harsh winters characteristic of Québec.

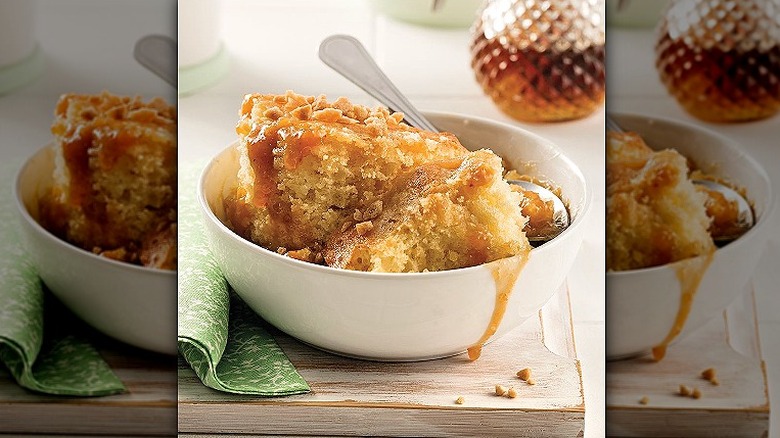

Pouding chômeur

Pouding chômeur, or pudding of the unemployed, is a somewhat more recent invention of Québec yet nonetheless evokes the legacy of the settlers who made their way to New France from their homes in France. It is a dish that evolved during the Great Depression as a means of creating something delicious out of modest and available ingredients. Historians believe that female factory workers combined stale bread with syrup made of butter and sugar to create a caramelized bread pudding. This unctuous dessert provided fuel and a sweet diversion to hard-working Quebeckers in a time when hardship was a part of daily life.

By 1939, the bread became replaced by a white cake batter and the sugar with the Québécois delicacy of maple syrup. Variations today are as diverse as households, with some including citrus, nuts, and cream. Pouding chômeur's modern iteration often gets likened to an upside-down pineapple cake sans pineapple but with the syrupy sweetness of the moist cake batter.

Craft micro-breweries, cider mills, and distilleries

It would be impossible to talk about the culinary traditions of Québec without mentioning the legacy of its breweries, distilleries, and cider mills. Early settlers brought with them the craft of brewing beer as well as distilling hard liquor. The first commercial brewery, and the first to export beer to the West Indies, was established in Québec City in 1688 by Jean Talon, also known as the Great Intendant. In 1786, John Molson founded his eponymous brewery in Montréal; it's known as the oldest brewery in North America today. The first rum distillery, the St. Roc Distillery, was founded in Québec City in 1769.

Cider making was likely the product of early British settlers, who often drank cider to prevent scurvy. However, the first apple tree was planted by French apothecary Louis Hébert in 1617 in Québec City. Cider today is big business in Québec, thanks to the distinctly cold climate, which helps give the fruit an extremely high sugar content. Many microdistilleries, micro-breweries, and cider mills offer tours and tastings throughout the region. These libations are effective in warming up after a cold day and are refreshing paired with heartier foods like tourtière, poutine, fèves au lard, and creton.